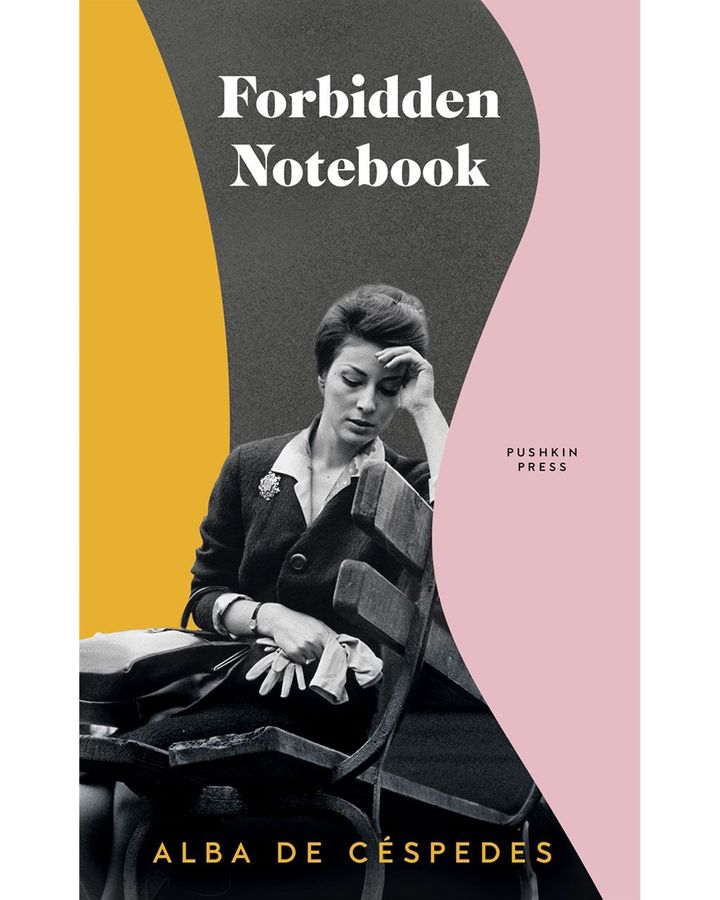

There is always an illicit thrill in reading someone else’s diary – even when it’s fictionalised. But rarely has uncovering someone’s innermost thoughts and desires felt as powerful as in Alba de Céspedes’ 1952 novel, Forbidden Notebook. From its opening line – “I was wrong to buy this notebook, very wrong” – the reader knows that what the book’s protagonist is sharing with us is somehow dangerous. In this case, a 43-year-old married mother of two living in post-war Italy is, for the first time, daring to express her honest thoughts, feelings and desires – if only to herself, on the pages of a notebook.

More like this:

– The radical books rewriting sex

– The most beloved French writer ever

– A Soviet novel ‘too dangerous to read’

If reading her diary entries feels like uncovering a secret, that feeling is only heightened by the fact that the novel itself has been out of print for decades. It has recently been reissued, first in Italy, and now in a new English language translation by Ann Goldstein. Goldstein is best known for translating Elena Ferrante’s works, and it was Ferrante who first alerted her to Alba de Céspedes, with the author referencing her in her non-fiction 2003 book Frantumaglia: A Writer’s Journey. “She mentions her twice in Frantumaglia actually,” says Goldstein. “She has this list of writers who are encouraging, and De Céspedes is one of them.” Goldstein then tried to track De Cespedes’ work down but struggled to find it. “I was interested in her, but I couldn’t find any of her books. It was crazy.”

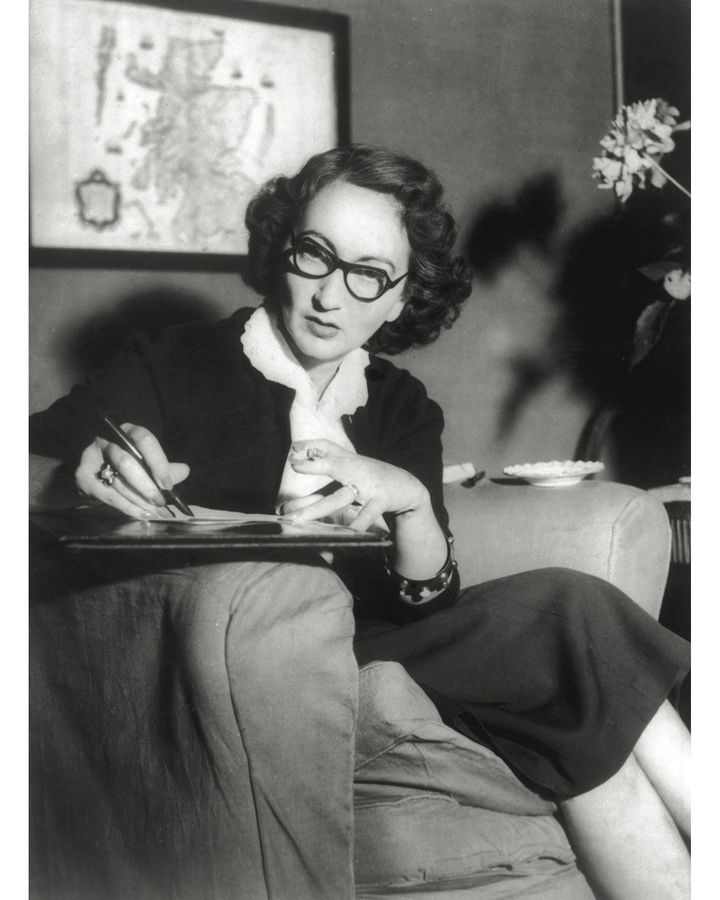

In her day, Alba de Céspedes was one of the most popular authors in Italy, widely read not just in her own country, but many others too. “She was very well known in her day and then just kind of faded to almost obscurity with many other women writers too,” says Goldstein.

When Goldstein finally got hold of a copy of Forbidden Notebook – published in Italian as – she was enthralled. “It was just stunning in how modern it seems to me,” she says. “The things that she discovers, she sees, it’s what we all struggle with still, and that was a little alarming. Immediately you’re just so pulled into it and engaged, it’s just amazing. I just feel like everybody should read this book.”

She’s not the only person to be dazzled by De Céspedes’ writing. Last year’s Nobel Prize for Literature winner Annie Ernaux said: “Reading Alba de Céspedes was, for me, like breaking into an unknown universe.” The author Jhumpa Lahari is also a fan, contributing a foreword to the new edition of Forbidden Notebook, in which she writes that it still “blazes with significance. Women’s words are still laughed at, still silenced, still considered dangerous. De Céspedes vindicates, artfully and ardently, a woman’s right to write – a right that must never be taken for granted.”

Reading between the lines

The book takes the form of a series of diary entries made by 43-year-old Valeria Cossati in Rome in 1950. She is a wife to Michele and a mother of two grown-up children, Mirella and Riccardo. Somewhat unusually for her generation, she also has an office job.

One Sunday morning she goes to the tobacconist to buy cigarettes for her husband when she notices a pile of notebooks in the window – “black, shiny, thick, the type used in school”. When she asks to buy one, the tobacconist tells her it is forbidden, as by law he is only allowed to sell tobacco on Sundays. She pleads and he gives in, insisting she “hide it under her coat” so the guard doesn’t spot it.

Once home, it becomes no less clandestine, as she keeps it a secret from her family. She writes her name on it – a name that feels lost to her, as her husband calls her “mamma” like the children, and her parents call her “bebe”. When, at dinner one night, she casually floats the idea of keeping a diary, her family laugh at her, incredulous at the idea she might have thoughts worth recording. “What would you write, mamma?” says her husband.

At first, she too feels she has nothing to write about aside from the “daily struggle” to hide the notebook – moving it from sewing basket to linen cupboard to suitcase. She has no room of one’s own, not even a drawer of one’s own. The notebook becomes her only private space.

But soon she is sharing more details – her inability to connect to and understand her daughter, her disappointment at her son’s choices, her stale marriage. She stays up into the early hours, feigning insomnia, to find the time and privacy to write.

In recording her thoughts and feelings, she starts to rediscover who she is outside of her family, uncovering needs and desires that had been overtaken by her domestic duties. “I’d always thought I was transparent, simple, a person who had no surprises either for myself or for others,” she writes.

There is a growing chasm between the person she presents to her family and friends, and the self she reveals in the notebook. “I find time to look at myself, to write in my diary.” As she starts to rediscover herself as something more than a wife and mother, so do others too – including her boss, who she starts to spend more and more time with.

But in examining her life so closely, she becomes increasingly restless. “The better I know myself, the more lost I become,” she writes. By the end of the book, the freedom her writing brings turns to fear. “Facing these pages, I’m afraid. All my feelings, thus dissected, rot, become poison and I’m aware of becoming the criminal the more I try to be the judge.”

The novel was originally published as a serial in a magazine, over the same six-month span as the diary entries in the book. Like her protagonist, De Céspedes also kept a diary – though her own life was far removed from that of Valeria’s. Born in Rome in 1911 to a Cuban father and Italian mother, De Céspedes’ grandfather was Carlos Manuel de Céspedes, who led Cuba’s fight for independence from Spain and served as the country’s first president. Her father also briefly served as president. Alba was married at 15, had a child at 16, and divorced by 20. She then began a writing career, initially as a journalist and later as a novelist and screenwriter. She was jailed twice for anti-fascist behaviour in 1935 and 1943, and in 1948 founded a literary magazine, Mercurio, that published writers including Ernest Hemingway and her contemporary Natalia Ginzburg. In the 1950s, she wrote a popular advice column. “Her life was quite different [from Valeria’s],” says Goldstein. “But what is the same is the issues that she faced, like struggling between marriage and her career and what it meant to be a woman and whether women could or couldn’t do certain things, and if not, why couldn’t they?”

The personal is political

De Céspedes was writing at a time when women were pushing for change in Italy – only finally getting full voting rights in 1945. “Her first novel, [There’s No Turning Back], is about a group of women all struggling with what their life is going to be, struggling against men and against all the restrictions that are put on them,” says Goldstein. “The fascists tried to keep it from being published because this was not the idea of women that they wanted to be out there.” The book was eventually published in 1938, to great success. “It sold incredibly. It was a bestseller, and the one after that was also a bestseller. So people really responded, women responded to her.”

De Céspedes’ writing may have described lives more mundane than her own, but in tackling domestic life – and the interior lives of women – with such radical honesty, she would go on to inspire other female writers to do the same, including Elena Ferrante.

Goldstein – who knows Ferrante’s work better than anyone – instantly saw similarities between the two when she first read De Céspedes. “With Ferrante’s characters, there’s a huge difference in class and other details, but I think that they’re still facing very similar issues of becoming yourself, of figuring out what is it that being a woman does for you and doesn’t do for you, what particular struggles you have in society, in the family, and all those different ways.”

De Céspedes’ success might not quite have matched that of Ferrante – whose quartet of Neapolitan novels alone have sold more than 15 million copies, been published in 45 different languages and spawned a critically acclaimed TV adaptation – but in the 1940s and 50s she was one of Italy’s most popular and well-known writers. So what happened?

Adam Freudenheim, publisher and managing director of Pushkin Press, the UK publisher of De Céspedes, thinks her popularity – especially as a woman – may have worked against her with the literary establishment of the time. “There could be a sort of snootiness about things that are successful and popular,” he says. “These were books that were printed and published and well enough received at the time and they often sold well, but they were often not valued as highly by the establishment, which was, of course, largely male. Often they were sort of seen as women’s writing for women.”

Yet while she faded from view in Italy, there was one place where her popularity soared. Following the election of Mohammad Khatami as President in 1997, Iran was going through something of a literary revolution with the government relaxing censorship, resulting in many books that had not been allowed before being published or republished. Writer and historian Arash Azizi was a teenager in Iran in the early 2000s. “If you went into a coffee shop in Iran in those days everyone was talking about books. Literature was really seen as this powerful thing that can really change the world.”

Bahman Farzaneh, a highly regarded Iranian translator who has translated books from Spanish and Italian – including Gabriel García Márquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude – translated many of De Céspedes’ works. “When you have someone like Bahman Farzaneh translating a book, you buy it just for the translator. They have the role of a cultural mediator,” says Azizi. Several of De Céspedes’ books were published in Persian, but Azizi says the one that stood out was Forbidden Notebook. “It was one of the most identifiable books of that era. Without fail, friends from Iran that are my age, they all remember the book.”

He recalls it being especially popular among women – not only his peers, but women in their 30s, 40s and older. “I remember many of my female friends related to how the main character’s husband calls her ‘mamma’, which she found very frustrating. They too wanted to be known as more than mothers.”

The concept of a hidden diary, a space for recording thoughts that you weren’t allowed to share publicly, resonated for those living in a repressive society. “What I really loved personally was this confessional tone,” says Azizi. “This idea that you can reach a kind of emancipation by the power of words alone. For someone growing up in the repressive Islamic Republic, it was really powerful, because of all the things we couldn’t do. We did live this double life.”

Azizi is delighted more people will now discover the book. “I’m very excited that something that I grew up with can now be shared by my friends in the United States and around the world. The book is really a testament to that period of my youth, as well as a testament to the power of literature.”

So, why is De Céspedes being rediscovered now? “I think Ferrante has a lot to do with it,” says Goldstein, “Her popularity really led people to look for other Italian women writers.” Freudenheim says there’s been a resurgence of interest in women’s writing from the late 1940s to 60s in general – and De Céspedes is part of that. Pushkin is planning to publish two more books by De Céspedes over the next two years – Her Side of The Story (1949) and her debut novel (There’s No Turning Back).

“Literary rediscoveries are really exciting, full stop, but sometimes you can’t actually imagine very many people reading them, because they’re quite difficult or abstruse or dated in a way that doesn’t resonate,” says Freudenheim. “What’s so exciting to me about this novel is that it is just an incredibly readable book, which is heartbreaking at the same time and very moving. It’s a page-turner that has a lot to say. Everyone I know who has read it is struck by that.”