A century ago, in 1923, crime fiction was truly flourishing. Agatha Christie’s second novel featuring her Belgian detective Hercule Poirot, Murder on the Links, was published. Dorothy L Sayers burst on to the scene with her debut novel Whose Body?, and introduced the world to Lord Peter Wimsey. Meanwhile Dublin-born detective author Freeman Wills Croft published The Groote Park Murder, his fourth novel, and went on to write 30 more.

More like this:

– What Agatha Christie says about Britain

– The ultimate spy novel

– The best gothic books of all time

This period is known to aficionados as the Golden Age of Detective Fiction. However in recent years, books by those authors have earned a new label: “cosy crime”.

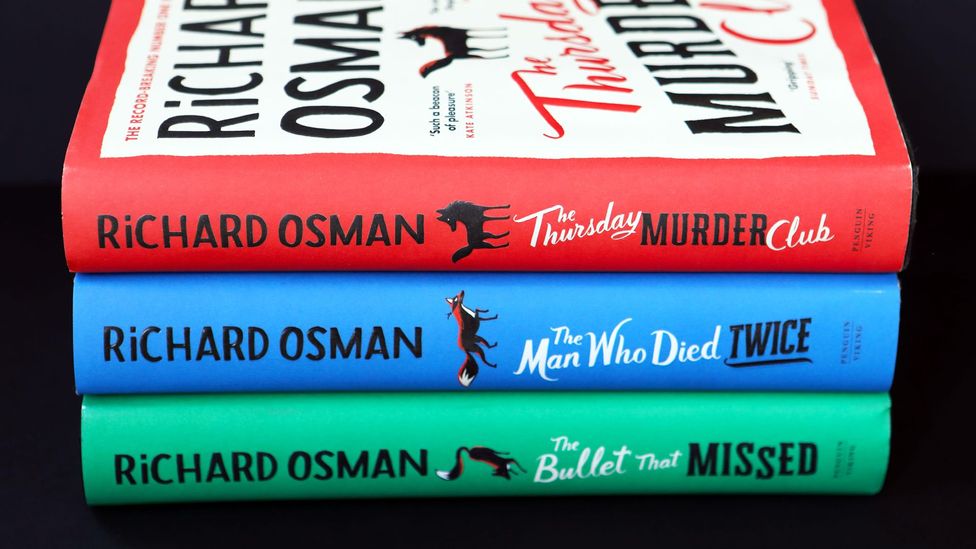

Cosy crime author Richard Osman is a British publishing phenomenon – and is now making waves in the US too (Credit: Alamy)

What’s interesting, though, is how cosy crime is also flourishing in the hands of contemporary British authors. Novels grouped into this new sub-genre by the likes of Richard Osman, Reverend Richard Coles, Janice Hallett, Ian Moore and JM Hall have been booming in the UK. Released on Tuesday, Osman’s novel The Last Devil to Die

So what exactly is “cosy” about a murder story? Well, the terminology distinguishes these novels from other kinds of crime fiction, such as police procedurals or psychological thrillers, which are often dark, gritty and upsetting.

Cosy crime, on the other hand, tends not to linger on the death that is often at the centre of the story. Of course, someone is usually dispatched in violent fashion, by way of poison, stabbing, shooting or a good cudgeling from whatever is to hand.

But cosy crime is more about the thrill of the investigation, generally carried out by an amateur sleuth or sleuths such as Christie’s Miss Marple or in Osman’s case, the residents of sleepy countryside retirement village. And the murder mysteries are often set against a typically English backdrop of, as former British Prime Minister John Major once extolled, “long shadows on county grounds, warm beer, invincible green suburbs”.

Police are generally baffled, suspects are bountiful, and murders are imaginative. Denouements are satisfying and leave the reader with the sense that crime does not pay and ultimately, all is well with the world.

The ‘cosy crime’ king

In becoming a publishing phenomenon, Osman had the advantage of having a well-established “cosy” persona thanks to his fame in the UK as a quiz show host, fronting popular series like Pointless and Richard Osman’s House of Games. (Before that, he had found success behind the camera as a creative director at production company Endemol.)

In 2019, he landed a seven-figure publishing deal for the series began with The Thursday Murder Club. However, Osman tells BBC Culture by email that when he started writing the first book in 2017, he certainly wasn’t consciously setting out to write a “cosy crime” novel. “When I started writing The Thursday Murder Club, the successful crime books of the time were mainly dark psychological thrillers with unreliable narrators,” he says. “I just wanted to write an Agatha Christie-style thriller but with some humour and with a modern twist. A book I’d love to read, but couldn’t find. I’d never heard the term ‘cosy crime’.”

With its amateur sleuth in a rural setting, Agatha Christie’s Miss Marple series is quintessential cosy crime (Credit: Alamy)

He doesn’t necessarily think his books are cosy, anyway. “Lots of fabulously bad things happen under the cosy exterior,” he says. “But I wouldn’t say that Christie and Sayers were [cosy] either. So I’m not sure I’ve ever read a ‘cosy crime’ novel.”

This week has also seen the publication of Murder in the Blitz, the debut, World War Two-set cosy mystery by Flic (writing as FL) Everett, which will shortly be followed by the sequel, Murder on the Home Front.

She also thinks that there are misconceptions about what “cosy crime” can encompass. “By ‘cosy’, we often mean ‘not gritty’ – ie no forensic poking about, no dwelling on corpses, no sexual assault or child murders,” she tells BBC Culture. “But in recent years, it’s often used pejoratively to mean ‘a bit twee’. It conjures sunlit Cotswold villages and bumbling policemen, stock characters and easy solutions.”

But isn’t that the bread and butter – served with a nice cup of tea on the vicarage lawn – of cosy crime?

“I don’t think most ‘cosy crime’ novels fit that cliché,” says Everett. She points to Endeavour – the TV series that serves as a prequel to the long-running and critically-acclaimed Inspector Morse, which starred John Thaw. “I find it deeply cosy, because it’s set in the 60s in Oxford and is a wonderfully enjoyable watch, but it certainly isn’t twee. It’s full of beautifully realised characters, tricky plots, and they actually do risk gritty storylines amongst the dreaming spires.

“Often ‘cosy’ simply means we care about the characters, and we know it will be resolved by the end of the episode, or novel. My own favourites in the genre are The ABC Murders and The Mirror Crack’d, by Agatha Christie.

“In short, yes, I am a fan of the genre – partly because it’s much broader than people often assume.”

On screen as well on the page, cosy crime has been a staple of our cultural consumption long before we used the term. Go back to the 1980s and think of Angela Lansbury’s author-turned-sleuth Jessica Fletcher in the phenomenally successful Murder She Wrote; the US TV series was perhaps the epitome of cosy crime, and indeed shows that the US stole something of a march in presenting contemporary shows that deliberately harked back to the Agatha Christie mould of storytelling.

More recently, British series such as Midsomer Murders, a procedural set within country villages where increasingly outlandish murders (burned alive in a wicker man? Drowned in a bowl of jellied eels? Death by numerous medieval weapons?) and Death in Paradise, set on the idyllic Caribbean island of Saint-Marie, have been quintessential cosy crime hits.

Murder She Wrote, featuring Angela Lansbury as an author-turned-detective, brought cosy crime to a mass US audience in the 1980s (Credit: Alamy)

Look at the schedules on broadcasters such as PBS Masterpiece and especially Acorn TV, which packages up a lot of British content for US audiences, and they’re stuffed with more and more shows of this type – the upcoming Marlow Murder Club, from Death in Paradise creator Robert Thorogood; Death in Paradise sequel Beyond Paradise; Magpie Murders; Whitstable Pearl; Grantchester and The Madame Blanc Mysteries, to name but a few. “In America, ‘cozy’ crime is a huge thing,” says Osman, nodding to the divergent American and UK spellings of the word. “And around the world I think people love British humour and warmth. And also British murder of course.”

The cosy crime dissenters

Everybody, it seems, loves cosy crime. Well, maybe not quite everybody.

Last year, journalist and writer James Greig wrote a scathing piece about Osman’s novels for the website Gawker headlined “The Thursday Murder Club Books Are Criminally Bad”. Yet he insists to BBC Culture that “I don’t dislike cosy crime per se – I like Janice Hallett’s novels, for example.”

Hallett is a British journalist and author whose debut novel The Appeal was the UK’s second bestselling fiction debut of 2021, and won the 2022 Crime Writers’ Association New Blood Dagger award. Her novels’ covers share a look with Osman’s – lots of large, slightly archaic typography in primary colours and small, often pastoral illustrations. Why does Greig like those and not, say, Osman’s?

“I guess the problem is if you actively strive for ‘cosiness’ the effect is usually very twee and insipid,” he says. “I think a lot of these writers are trying to emulate Christie without understanding what makes her good: obviously yes, there is an element of cosiness to the settings of her novels, no doubt enhanced by the passing of time, but there is also pain, loss, malice, dread and evil etc in her work, and the satirical elements are often quite acerbic – I just don’t get that with Osman etc at all, and I don’t find crime fiction with all the edges smoothed over very compelling.

“So as I see it, the shift from domestic noir to cosy crime is the biggest downgrade in the history of commercial fiction,” he concludes. By “domestic noir”, Greig is referring to another sub-genre of crime that has flourished in recent years but has actually been around for much longer, even if it didn’t have a name. Often female-led (both in character and author terms), it concentrates on seemingly normal household settings with tensions bubbling under the surface, often giving way to psychological drama. Bestselling examples include Gillian Flynn’s Gone Girl and Paula Hawkins’ The Girl on the Train.

The onrunning Midsomer Murders is among an ever-increasing range of British cosy crime TV series (Credit: Alamy)

However, while some readers might have preferred that crime novel fad, there’s no sign of cosy crime’s popularity flagging in the near future – and there are certainly plenty of cosy crime authors only just getting started. “I feel a strong affinity with this genre now, as I don’t particularly want to write ‘gritty’ crime,” says Everett. “I love being able to add little jokes, and historical detail, and I’ve no interest in grim pathologist detail – I’m focused on the characters and the mystery they need to solve.

Why cosy crime connects

“Cosy crime, at heart, celebrates the best of people alongside the worst – bravery, decency, doggedness alongside the darkness – and I suspect that deep down, I’m an optimist who fundamentally believes that people are usually good,” she continues. “I don’t want to write about serial killers and trauma, it depresses me. I have to spend months with these imaginary people, so it helps if I like them and enjoy their company.

Everett feels that cosy crime speaks to our need for resolution and neat endings in an often messy, unfocused world, and the longing to trust people to ultimately do the right thing. In a lot of other contemporary crime fiction, by comparison, the good guys don’t necessarily win – in fact, it’s often hard to tell, especially in morally ambiguous psychological thrillers and even police procedurals, who the good guys even are.

“I don’t find that need twee at all – I find it vital,” says Everett. “Particularly at the moment, when it’s so hard to trust politicians, the police, the press – it’s natural that we’d turn to a fictional world to see order restored and give us some reassurance that crimes get solved, bad people repent or are punished and good people are rewarded.”

For Osman, genre classifications are redundant anyway. “No one should ever write in a ‘genre’,” he says. “Just write what you’d love to read. Entertain and surprise people. That’s what Christie did, and that’s why we’re still talking about her 100 years later.”