Every element of the natural world tremored with significance in Vincent van Gogh’s world. Sunflowers were his symbol of joy and devotion. Stars were glimmers of heaven. Why did cypress trees become his symbol of fortitude?

More like this:

– The tragedy of art’s greatest supermodel

– 10 artworks that caused a scandal

– The 300-year-old pet portraits

In the summer of 1889, Vincent van Gogh arrived as a voluntary patient at the asylum of Saint-Paul-de-Mausole, in Saint-Rémy. His recuperation from a series of breakdowns was overseen by a team of doctors, but the artist had a self-prescribed remedy. It was to engage with nature and embroil himself deeper with his art. And he became increasingly fixated with one feature of the surrounding Provençal countryside: its muscular, ancient cypress trees.

Van Gogh’s Cypresses, a new exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, puts the spotlight on the tree that became the artist’s obsession. “This is the first exhibition to focus on Van Gogh’s cypresses,” its curator Susan Alyson Stein, tells BBC Culture. “It is an unprecedented and entirely new perspective. It reveals the back story behind his long-standing interest in the motif.”

Here’s what four key artworks in the exhibition reveal about Van Gogh’s symbol of resilience.

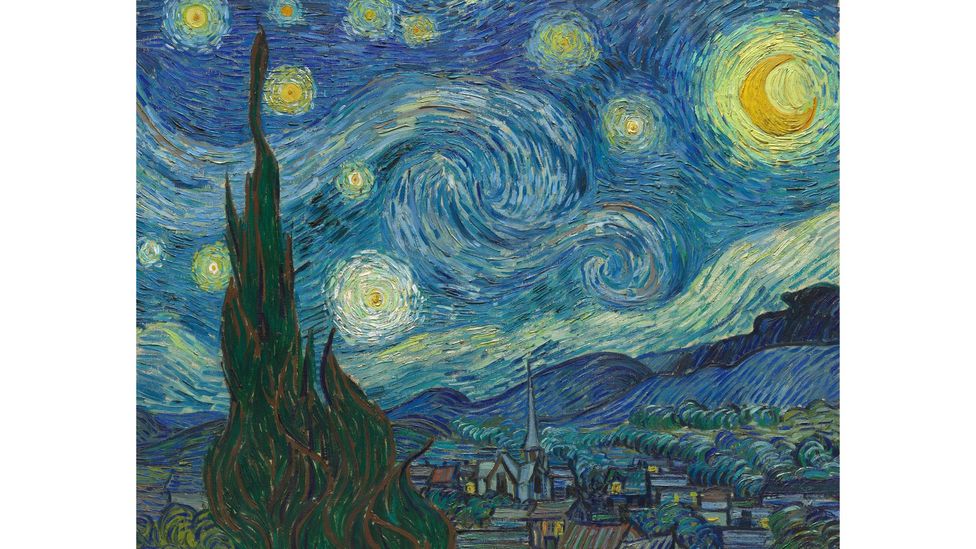

The Starry Night, June 1889 (Credit: MoMA, NYC)

1. The Starry Night, June 1889

“It’s beautiful as regards lines and proportions, like an Egyptian obelisk. And the green has such a distinguished quality.” This written description of cypresses was noted by Van Gogh at his asylum in Saint-Rémy, and you can see it expressed in visual form in all his canvases depicting the tree in 1889 and 1890, particularly The Starry Night.

He had discovered an equivalence in the form of the cypress and obelisks after reading about Egyptian architecture displayed at the Paris World’s Fair of 1889. As well as expressing endurance through history, cypresses and obelisks possessed a graceful simplification of form, and linked Earth to sky, a feature that Van Gogh used most dramatically in The Starry Night. Egyptian obelisks were symbols of Ra, the Sun God and, like cypresses stretched vertically into the empyrean, linking the cold ground to the fire of the heavens, expressing hope and immortality.

By painting cypresses like obelisks, Van Gogh’s aim was to express the grandeur, timelessness, and monumentality of nature, something he could draw solace from at his moment of despair.

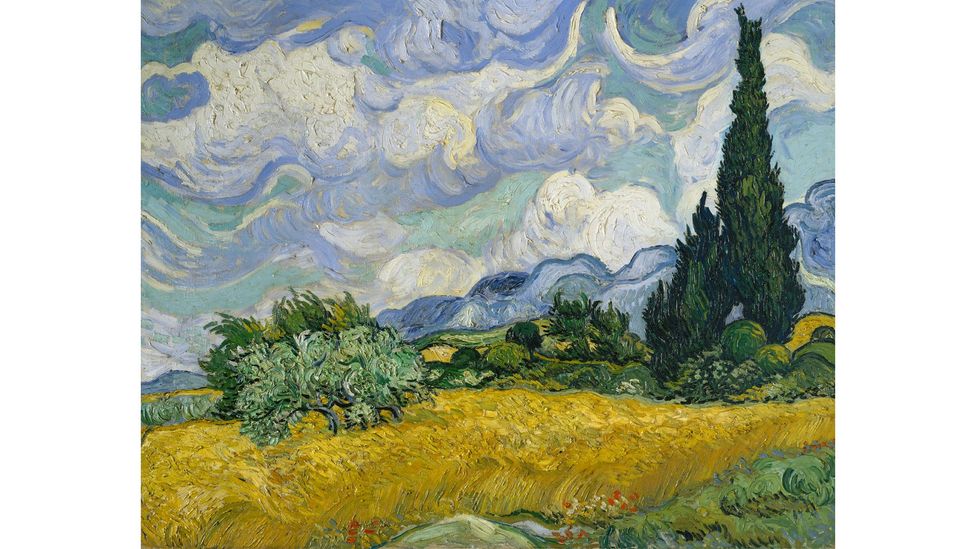

Wheat Field with Cypresses, June 1889 (Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art, NYC)

2. Wheat Field with Cypresses, June 1889

“The cypresses still preoccupy me, I’d like to do something with them like the canvases of the sunflowers because it astonishes me that no one has yet done them as I see them,” noted Van Gogh in a letter to his brother, Theo. He had been thinking about cypresses and their expressive potential ever since he had arrived in Provence in February 1888, yet the fruition in his art came about after his arrival at Saint-Rémy. In admitting to wishing to “do something with them… as I see them”, Van Gogh confessed to a key aspect of his personal resilience: the struggle for professional success.

“He was always very mindful of what was going on in in the art world,” Stein explains. “He was very ambitious, and always thought of his legacy. He did identify the cypresses really from the start as a motif which resonated on many different levels. It spoke to his idea of a motif emblematic of Provence that would set him apart.” Cypresses came to dominate his work, serving as a kind of signature and a symbol of the region he loved, in landscapes like Wheat Field with Cypresses (June 1889).

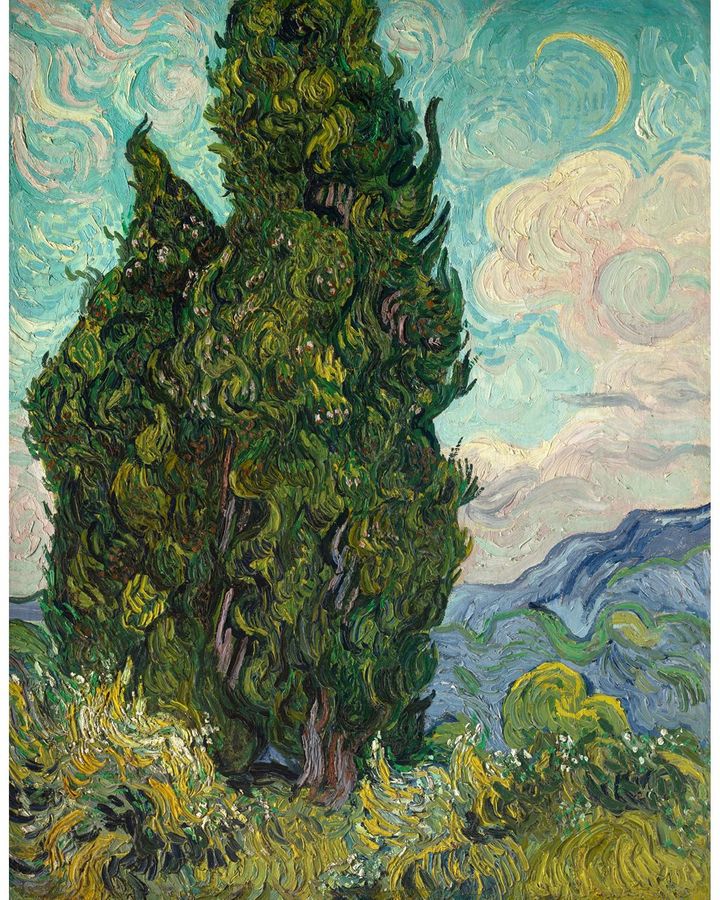

Cypresses, June 1889 (Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art, NYC)

3. Cypresses, June 1889

Finding a unique style of painting nature was also on Van Gogh’s mind and he considered it an important stepping stone on the road to fulfilment. On first arriving in Provence, he had wanted to establish an artists’ colony, and particularly craved the presence of his colleague, the artist Paul Gauguin whose work he admired. The Dutchman was intrigued by Gauguin’s bold ideas about art and its spiritual role. Gauguin believed that artists should study nature directly, but then apply the powers of human imagination to modify appearances by intensifying shapes and colours. However, even though Gauguin joined Van Gogh in Provence in October 1888, he left that December, disturbed by the Dutchman’s erratic behaviour.

But Van Gogh persisted in making cypresses a vehicle for artistic singularity. Cypresses (June 1889) exemplifies his unique approach – painting the tree as if it was a frozen column of smoke, coiling upwards with twisting dashes of the brush, using the same technique as he did for the flow and flicker of the surrounding clouds and fields. The style was a product of Van Gogh’s deep feelings about nature. Energies are represented as responding to one another – the potency of the soil’s minerals, which are drawn up by the cypresses, are unified in ecstasy with the dynamism of wind, hills, and moon.

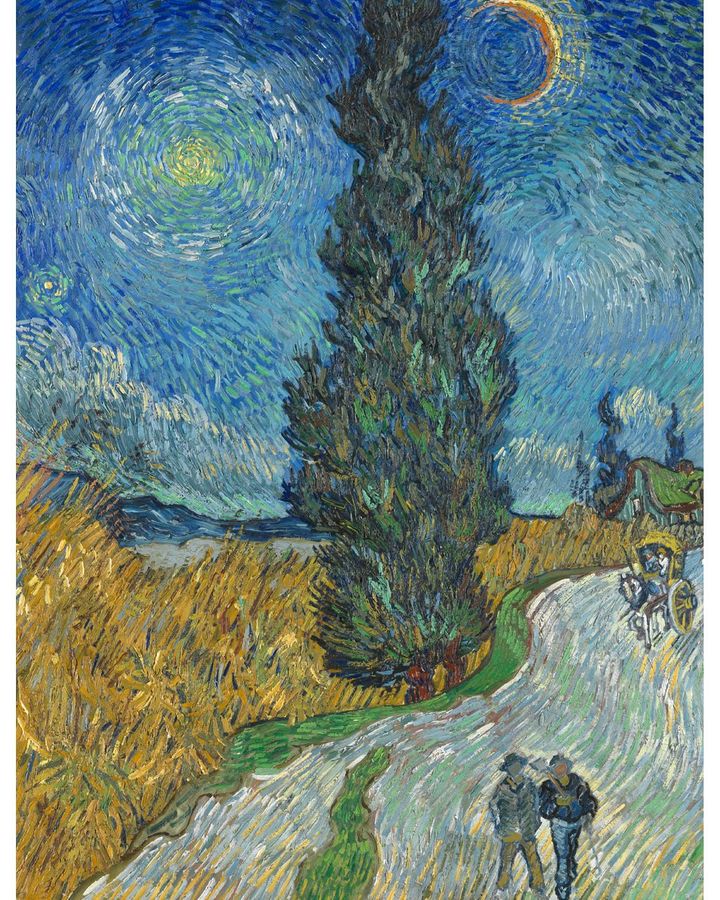

Country Road in Provence by Night, May 1890 (Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art, NYC)

4. Country Road in Provence by Night, May 1890

“It’s the dark patch in a sun-drenched landscape,” wrote Van Gogh to his brother Theo about the tone of the cypress trees that surrounded him. “But it’s one of the most interesting dark notes, the most difficult to hit off exactly that I can imagine.” The darkness that Van Gogh perceived echoes traditional associations of cypresses with death and immortality – important concepts to an artist seeking a certainty amid life’s vicissitudes. Cypresses were often planted in cemeteries and their wood used for coffins. In the writings of classical authors like Ovid and Horace, they appeared in the context of bereavement. These associations persisted through the centuries, reappearing in the plays of Shakespeare and the novels of Victor Hugo, authors that Van Gogh knew and admired.

“He appreciated that these were century-old trees, and certainly knew their associations with rebirth, immortality and death,” Stein explains. “From the get-go he associated them with stars and wheat, which were his tried-and-true metaphors for eternity and the eternal cycles of life. They stood for millennia as protectors and guardians of the countryside from the fierce northerly mistral winds.”

In Country Road in Provence by Night, the cypress dominates the centre point of the composition, dividing a star and the moon in the night’s sky. Below are two men – possibly symbolising Van Gogh and Gauguin – walking away from the ancient, obelisk-like tree.

Shortly after painting Country Road in Provence by Night, Van Gogh left Provence and moved to a town near Paris, still coveting the idea of a creative partnership with Gauguin. The cypress in the painting seems like a final homage to the bedrocks of nature, spirituality, artistic ambition, and cultural history that had sustained Van Gogh in the south of France.

Van Gogh killed himself in July 1890. At his funeral, the artist’s coffin was strewn with sunflowers and cypress branches, the artist’s two signature motifs. Nowadays we associate the artist mainly with sunflowers – a symbol of temporal devotion and transient joy. Van Gogh called his sunflowers “the complimentary and yet the equivalent” to his cypresses, which stood for the steadfast and the eternal.

Cypresses were Van Gogh’s symbol of resilience. As Stein puts it, the exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art shows the stalwart character of Van Gogh: “his resourcefulness, his determination to carry on, his ability to face the challenges that stood in his way with new fresh invention”.

At his lowest ebb, he saw cypresses as giant totems in the landscape, emblems of the power of nature, protectors of the Provençal countryside. He drew upon history, his own sense of ambition and traditional symbolism from art and literature to inform his vision and create an enduring icon – of deep time, of ambition, of uniqueness, and of inner strength in the face of life’s turbulence.