This month, the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam opens its doors to the largest ever retrospective of Johannes Vermeer, bringing together 28 of the artist’s 37 extant paintings. It is an intelligent, carefully curated, and stylish exhibition, and a genuinely once-in-a-lifetime event. What first strikes you at the exhibition is Vermeer’s incredibly realistic painting technique, particularly his skill in depicting light. How it gives shape and volume to objects, and how different varieties of sunlight, filtered through windowpanes and tinged by cloud-cover, modify the colours of objects, and make textiles seem to sparkle.

But Vermeer’s art is like an ice-covered lake, where hidden life lurks beneath a deceptively cool and crystalline surface. Within the artist’s beautifully constructed visual reality is another dimension: an invisible reality of ideas spoken in the language of symbols. “For Vermeer, symbolism was crucial,” Pieter Roelofs, one of the co-curators of the exhibition, tells BBC Culture. One of the curators’ interests is how symbols functioned in Vermeer’s art to communicate religious ideas. “They helped in presenting his paintings as a kind of virtuous example.”

More like this:

– The mysteries of Girl with a Pearl Earring

– Why Vermeer’s paintings are less ‘real’ than we think

– Who was the Girl with a Pearl Earring?

Here’s how five seemingly random objects – a curtain, a footwarmer, a jacket, a set of weighing scales, and a glass orb – expose the deeper meanings of Vermeer’s paintings.

1. The curtain in Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window (1657-8)

Vermeer was 25 years old when he painted Girl Reading a Letter by an Open Window. It marks a new turn in the artist’s career where he moved away from religious scenes and began to focus on intimate, somewhat introverted episodes from domestic life. At the hub of this artwork is the silent tranquillity of the woman’s absorption in reading. Generations of art lovers have admired the painting’s exquisite rendering of artefacts and human character. And yet one detail purposefully breaks this perfect illusion.

The green curtain that covers a fifth of the composition is shown suspended by a rail and brass rings. In the Dutch Republic of the 17th Century, paintings were frequently covered with curtains to protect them, and Vermeer seems to have included it as a – an illusionistic trick of the eye tempting us to reach out and draw it aside.

It also recalls a story – famous in art history – described in Pliny the Elder’s Natural History (published in 77AD). It tells of two artists, Zeuxis and Parrhasius, who had a competition to judge the better painter. Zeuxis created a still life where the grapes were so realistic that when the painting’s covering was removed, birds flew down to eat them. When Zeuxis tried to unveil Parrhasius’s painting, he was astounded to discover that its covering was actually painted on. Vermeer’s curtain is an allusion to this renowned story to symbolise his skill and force us to question art’s exploration of illusion and reality.

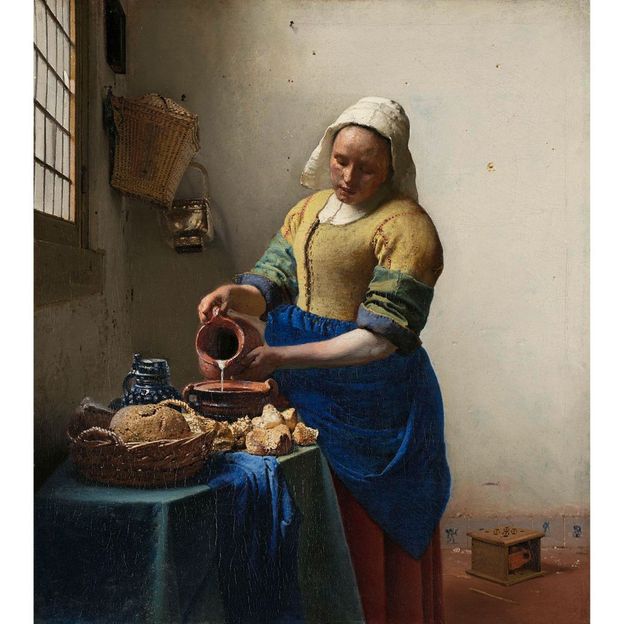

2. The footwarmer in The Milkmaid (1658-59)

The room is cold and humble, with damp spots on the wall and a cracked windowpane. The maid is doing one of the lowliest activities imaginable: making bread pudding from stale loaves and milk. However, the footwarmer at the bottom right-hand corner ingeniously transfigures the image’s meaning, making it much more than a document of daily life.

Footwarmers were designed to encase hot coals and were placed under women’s skirts whilst they worked at home in the winter months. In Vermeer’s painting, the footwarmer sits in front of a blue-painted tile depicting the love-god cupid and his arrow of desire. This combination of symbols had a specific meaning to a Dutch audience in the 17th Century. In genre paintings, footwarmers symbolised lust because they enflamed the body’s lower regions. They were often shown in combination with other euphemistic objects such as empty jugs to represent the sexual availability of milkmaids and female servants.

In Vermeer’s painting, the symbols of passion are present, but everything else suggests the woman’s respectability: she is looking away from us, her body is shrouded in heavy garments, and she faces away from the symbols of prurience towards her domestic chores.

3. The weighing scales in Woman Holding a Balance (1662-64)

A young woman is watching a set of weighing scales gradually settle their equilibrium in a noiseless, curtain-drawn room. The objects on the table suggest that she is about to value the worth of various coins and pearls, but the presence of a painting hanging directly behind her suggests a more profound unfolding of events.

Her head obscures most of the painting, but its exposed upper section reveals Christ in Judgement. In this painting-within-a-painting, Jesus is doing what the woman is doing – he is weighing something. Except his work is deliberating souls on Judgement Day.

Vermeer was intensely religious, and he encrypted several of his artworks with symbols of spirituality. He lived in the devoutly Protestant Dutch Republic, but was a Catholic convert, and the scales might be an allusion to his minority faith. The Jesuit founder St Ignatius of Loyola (1491-1556) had advised that good Catholics should weigh up their sins against their goodness when they pray: “I must rather be like the equalised scales of a balance ready to follow the course which I feel is more for the glory and praise of God, our Lord, and the salvation of my soul.”

Vermeer was connected to the Jesuits in various ways throughout his life: it is believed that he married his wife in a Jesuit church near his hometown of Delft, and he even named one of his sons Ignatius after the Jesuit founder.

“Vermeer was overwhelmed with Catholicism,” Pieter Roelofs tells BBC Culture. “He had at least seven daughters and the paintings he created could have functioned as a kind of example to his own children in his own household.”

4. Textiles in Girl with a Pearl Earring (1664-67)

Girl with a Pearl Earring seems like another image of a fleeting, naturalistic moment. It is an example of a “tronie”: a Dutch genre of art that showed an unnamed figure in an interesting costume. Her headgear was intended to show her as an exotic or ancient character, and her pearl to convey spiritual purity or earthly beauty. Her jacket is made of an iridescent fabric that seems to be a grey/blue in shadowy areas and gold in the direct light. In Vermeer’s day, the representation of fine material was of special interest to collectors, who rated painters by their ability to evoke them in art. Vermeer’s father worked in the fabric trade, giving the artist an early understanding of the beauty and significance of precious cloth.

Vermeer is known to have used the symbolic language of art defined in Cesare Ripa’s book on allegories, the Iconologia, which was translated into Dutch in 1644. In the Iconologia, the figure of Pittura – “Painting” – is represented with a shot-silk dress of colours that change in the light. Vermeer’s model is also decorated with the three primary colours that are the bedrock of a painter’s craft – red lips and clothing of yellow and blue. In Vermeer’s painting, the young woman – painted with open mouth and gazing directly at us to enhance her desirability – is turning as if to disappear into the darkness. Is she an embodiment of art itself, whose perfect ideals are always tantalisingly out of reach?

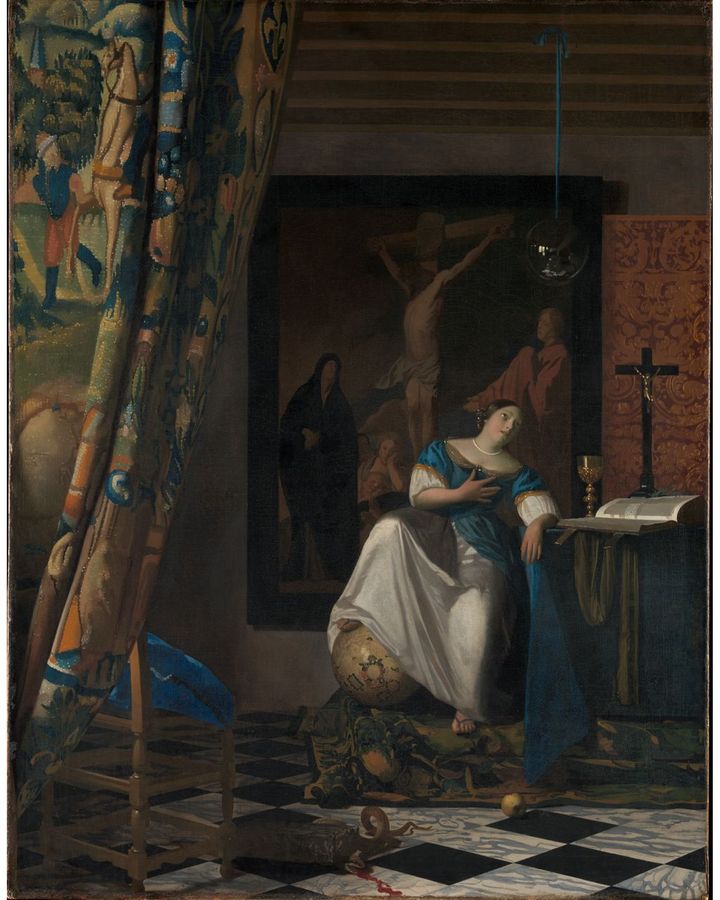

5. The glass sphere in The Allegory of Faith (1670-74)

Vermeer’s religious faith is expressed most forcefully in his late allegorical painting The Allegory of Faith. The main character is a personification of Catholicism, and her appearance and gestures are taken once again from Cesare Ripa’s Iconologia, this time from a figure denoting of “Faith”.

But the glass orb above her head is not in Ripa’s book, and it took scholars decades to work out what it meant. In 1975, the art historian Eddy de Jongh discovered the emblem – represented exactly as it does in Allegory of Faith suspended by a ribbon – in a book titled Holy Emblems of Faith, Hope and Charity by the Flemish Jesuit Willem Hesius. It was accompanied by a motto: “It captures what it cannot hold”.

A short verse in the book explains that the orb is like the human mind. In its panoramic reflections, “the vast universe can be shown in something small” – and likewise “if it believes in God, nothing can be larger than that mind”. The orb symbolises the mind’s interaction with God.

It might be added that all of Vermeer’s paintings are also like the orb, capturing passing events and ideas on their flat surfaces and sealing them for posterity. For all the paintings’ exceptional skill at capturing reality, Vermeer only enjoyed very modest success while he was alive. He created about two paintings a year, and the small amount of money he could earn from it meant that he couldn’t make a living by painting alone.

Perhaps his art appeals even more to us in the frenetic 21st Century because it offers a unique sense of calm. In Vermeer’s scenes, time appears to freeze in the crystalline sunlight and silence descends like a dead weight. But a vivacious world of symbols pulses beneath the surface: perennially relevant ideas about art, desire, materialism and spirituality, captured by Vermeer and lying in wait of discovery.