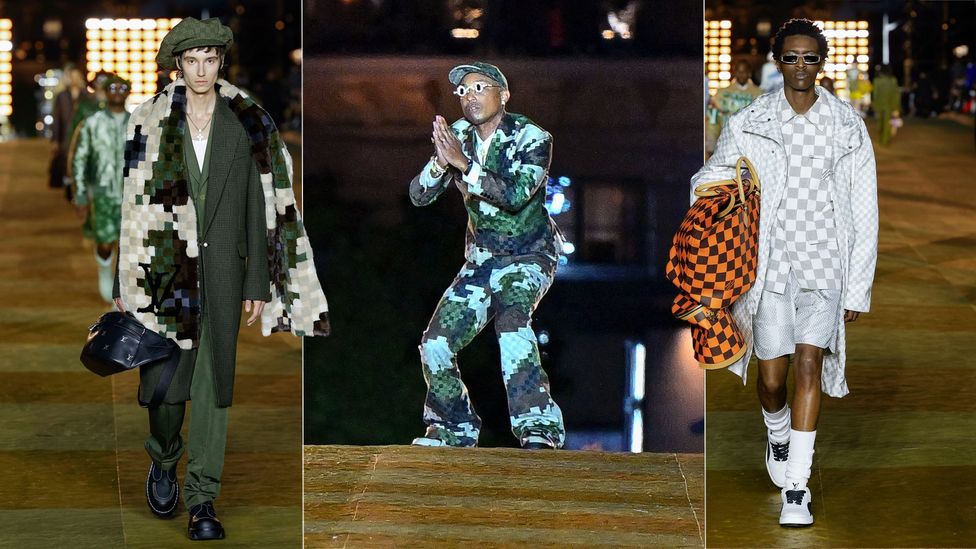

In February it was announced that Pharrell Williams would be the new men’s creative director of Louis Vuitton – a role that became vacant after the unexpected death of the US fashion designer Virgil Abloh in November 2021. Four months later, the revered musician and producer showcased his first collection at Paris Fashion Week. It included vibrant faux-fur jackets, the brand’s logo in bright colours across garments, and various camouflage pieces created by modifying Louis Vuitton’s signature Damier print.

More like this:

– The night hip hop was born

– The forgotten ‘godfathers’ of hip hop

– Eight people who rapped before hip hop

While this is not Williams’s first foray into the fashion world – he has collaborated with Louis Vuitton twice before, and with Chanel, Moncler and Adidas Originals – his role at Vuitton

Since the birth of hip hop in the early 1970s, when teenagers from the Bronx threw a back-to-school party, fashion has been an integral part of the scene. From oversized garments to bold colours to the co-opting and repurposing of luxury brands, the distinctive style that comes with the genre puts the personal tastes of individual artists front and centre, and has undeniably influenced fashion worldwide throughout its existence. “Hip-hop culture speaks to people globally because there is this thread of defiance, self-definition and uplifting others that’s universally appealing,” says Cassandra Hatton, Sotheby’s global head of science and popular culture, who in 2020 organised the auction house’s first-ever sale dedicated to the genre.

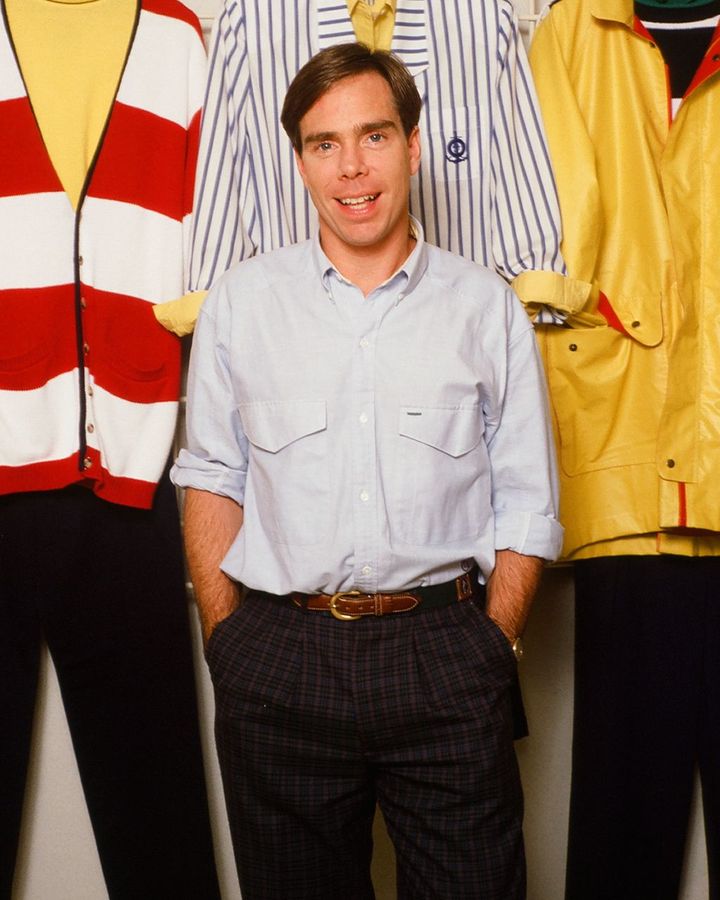

In the 1980s Tommy Hilfiger’s preppy designs were worn and endorsed by hip hop stars – today’s stars are more likely to create their own brand (Credit: Getty Images)

Hip-hop lyrics have long declared the importance of fashion in the genre. In 1992, Mary J Blige released What’s the 411? as part of her debut album of the same name. The single featured a rap by Maxwell Dixon that explicitly shouts out the US designer Tommy Hilfiger. “It was epic,” Hilfiger tells BBC Culture. “He was co-signing the brand, and it gave us credibility.” In the hip hop world, co-signing is when a usually successful artist endorses or supports another artist.

Then came a Saturday Night Live TV performance by Snoop Dogg in March 1994. Hilfiger recalls: “Snoop broadcast the brand to the world, wearing a red, white and blue striped rugby [shirt] with ‘Tommy’ emblazoned across the chest on SNL.” While Snoop Dogg’s outfit doesn’t appear out of the ordinary today, for many viewers at the time, it would have been the first sighting of a hip hop artist wearing Tommy Hilfiger, a brand now strongly associated with the genre. “Our designs had bold, bright colours, oversized silhouettes, and a playful prep vibe – they captured hip-hop’s relaxed energy,” says Hilfiger. “It was real and so much fun. We wanted to continue working with these exciting artists, so we started dressing stars of the time, including Puff Daddy, TLC, Destiny’s Child and Wu-Tang.”

For women, much of early hip-hop style came from re-working men’s clothes, and in 1997 US hip-hop artist Aaliyah starred in a Tommy Hilfiger fashion campaign wearing low-rise jeans with a pair of the designer’s boxers peeking out and a men’s shirt cut into a bandeau top. “She made it tomboy sexy,” Andy Hilfiger, brother and business partner of Tommy, tells BBC Culture. “Still to this day, people are dressing like that.”

Preppy affluence

But there is more to the appeal of brands like Hilfiger and Ralph Lauren than just how the clothes looked. It was that they were associated with preppiness and affluence. According to Elena Romero, co-curator of a recent Fashion Institute of Technology exhibition, Fresh, Fly, and Fabulous: Fifty Years of Hip Hop, part of hip hop’s attraction to luxury brands is aspirational. “That goes back to [hip hop’s] early roots, where so much of [luxury fashion] seemed so unattainable, and thus it was a status symbol,” she tells BBC Culture. Hip-hop artists and their fans were from multicultural working-class neighbourhoods who would be unable to easily afford luxury brands. “The whole idea of being on yachts and caviar dreams, those were lifestyles we had no access to,” Romero says, explaining that she grew up with hip hop herself. “And the celebrities of our community became our superheroes, who made it possible for us to see ourselves in that space and beyond.”

Dapper Dan was a lead proponent of logomania in hip hop’s early days – now he has a more official association with brands, including Gucci (Credit: Getty Images)

Logomania, where prominent branding is strewn over clothing, was hip hop’s most distinctive trend in the early days, and a nod to this was seen recently in Pharrell’s Louis Vuitton debut. Fashion designer Daniel R Day, known as Dapper Dan, considered the founder of logomania, opened Dapper Dan’s Boutique in 1982 in Harlem. Open 24 hours a day, seven days a week, it soon became a must-go-to spot for hip-hop stars such as LL Cool J and athletes like Mike Tyson. Dapper Dan’s custom pieces often used the logos of fashion houses such as Gucci, Fendi and Louis Vuitton, printed in excess across his creations. “I took brands that signify luxury and configured them in a way that had never been seen before,” Dapper Dan tells BBC Culture. “When hip hop started, Ralph Lauren gave them one horse, and Gucci gave them two Gs. I gave them a whole herd and more Gs than you could ever hope to see.”

Hip hop was also finding its way to Britain, with the release of singles such as Sugarhill Gang’s Rapper’s Delight in 1979, and Malcolm McLaren’s Buffalo Gals in 1982, which featured the New York hip-hop group World’s Famous Supreme Team. In the video of the hit song, outsized Vivienne Westwood hats and avant-garde make-up added a touch of quirky Britishness to the look.

Pharrell Williams’s appointment as creative director of Louis Vuitton menswear is part of a general shift in the fashion industry (Credit: Getty Images)

Dapper Dan notes that Europeans embraced his work even before middle and upper-class black communities accepted it. “Europeans said, ‘Look at what he took from here and made completely new”, Day says. “So when you go back to the 80s, you will see me in European magazines before I even appeared in a black publication.”

Paid in full

In the early 90s, Dapper Dan was forced to close his shop, after Fendi took legal action. “I had to go underground for 29 years, but I never stopped,” he says. Now, Day frequently works with those same labels that once overlooked its black customers, including Gucci, who announced a collaboration with Day in 2017. “That was a major move,” Day says. “Gucci, an international luxury brand, came to Harlem and allowed a designer from [the inner city] to have his own atelier to further this whole idea of hip hop fashion.”

These labels now collaborate with many contemporary hip-hop musicians and designers associated with the scene, and put them in leadership roles, as Louis Vuitton has done with Pharrell Williams. His predecessor Abloh was also known for his close ties to hip hop, and his fashion label, Off-White, has been worn by many contemporary rappers. This shift marks a new period in history. Rather than black hip-hop musicians simply wearing and endorsing the designs of white-owned brands, they are now creating their own pieces, and also having a direct say in what is being produced by the fashion houses they’ve long loved. “When people think of hip hop, they think just music, but they don’t really understand that hip hop is a culture,” says Sotheby’s Hatton. “It’s music and art and fashion and all sorts of different things intertwined. The people involved in music were having an impact on the fashion, and the people making the fashion were having an impact on the art.”