She almost always wore black, but in Woman with a Hat (1905) so many colours swirl around the canvas that Amélie Matisse’s dress is an indeterminate shade. She was a brunette, but her hair is a streak of fiery red paint, and her nose and forehead are green.

Putting the wind up the snooty Paris art scene at the Salon d’Automne of 1905, works such as this one with their noisy, unnaturalistic colours and childish flattened forms were dubbed “Fauves” (wild beasts) by a critic − and the name stuck.

More like this:

– The tragedy of art’s greatest supermodel

– 10 artworks that caused a scandal

– The 300-year-old pet portraits

Building on the work of Paul Cézanne and Vincent van Gogh, Fauvism’s untamed art freed colour from a uniquely descriptive, imitative function. Colour was now communicating emotion and its delineated planes prepared the way for the fractured geometry of cubism and the dawn of abstract art.

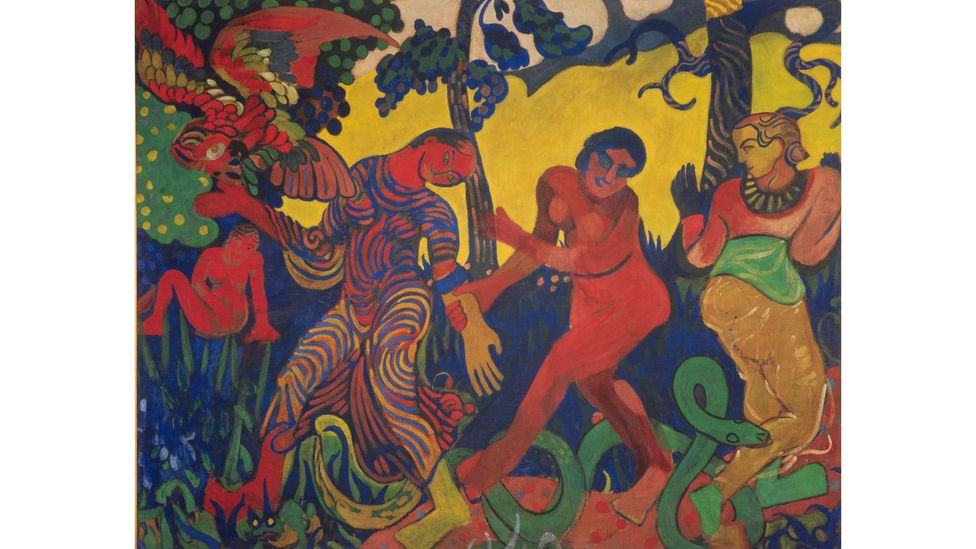

The Dance (1906) by André Derain (Credit: Privatsammlung)

Fauvism might have lasted just five years, but this autumn it is back in the limelight with Vertigo of Colour: Matisse, Derain, and the Origins of Fauvism on 13 October at New York’s Met, where the Fauves’ ground-breaking use of colour takes centre stage; and Matisse by Matisse, the largest ever exhibition on the artist, showing first in Beijing (until 15 October) and then Shanghai.

But despite this fervour for Fauvism, art history has not always seen the full picture. Matisse, Derain and Friends: The Paris Avantgarde 1904-1908, which opened at the Kunstmuseum Basel on 2 September, hopes to change this, and is believed to be the first gallery to explore the largely unacknowledged role of women in the movement.

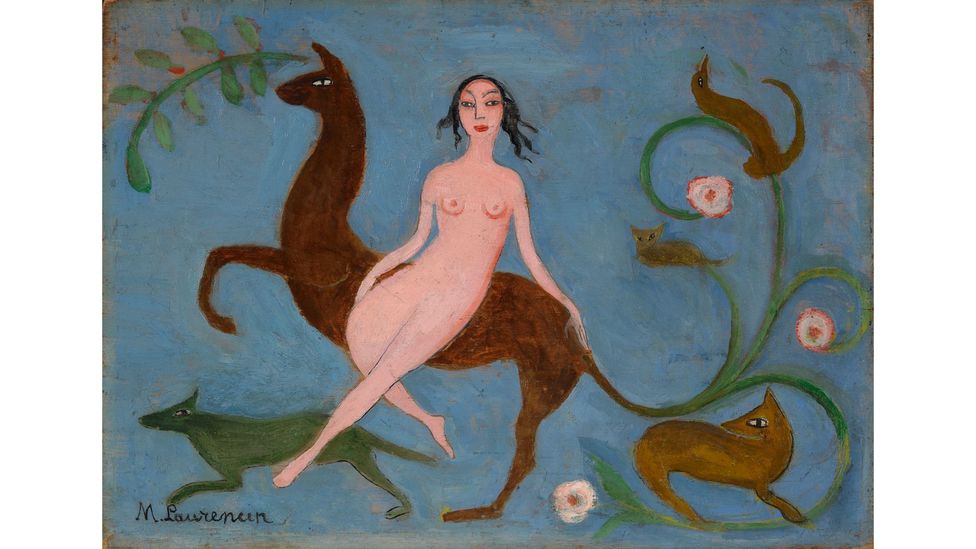

“The biggest misunderstanding about women in Fauvism is that there were none,” the exhibition’s co-curator, Arthur Fink, tells BBC Culture. He gives the example of Émilie Charmy, so much more than Charles Camoin’s muse, but “people just actively ignored her work”; and Marie Laurencin, sidelined by art history, but painted by Henri Rousseau, and “clearly part of the aesthetic discourses of the time”. And then there’s Alice Bailly, Suzanne Valadon, Sonia Delaunay, Gabriele Münter, Marianne Von Werefkin… Who? Quite.

Diane Hunting (1908) by Marie Laurencin (Credit: Musée Marie Laurencin, Tokyo)

But perhaps even more important than the female painters of the period is the debt owed to the women who enabled Fauvism from behind the scenes, yet enjoyed none of the applause. The visionary art dealer Berthe Weill, for example, had a keen eye for fresh talent, and provided support and exposure that helped drive the movement forward.

Weill, says Fink, “was not an accessory at all: she was a very, very strong woman… very autonomous.” Weill was one of the few art patrons to champion the work of women artists and, in 1902, the first to show Fauve work. Her protégés included Charmy, who painted her portrait, and Laurencin, whose nickname La Fauvette speaks to her importance within the movement.

Portrait of Berthe Weill (c 1920) by Émilie Charmy (Credit: Galerie Bernard Bouche, Paris)

The US art collector Sarah Stein (1870-1953), sister-in-law to the writer Gertrude Stein, was not just the passive subject of Matisse’s art, but a key figure in bringing early attention to his work, providing financial support and encouraging him to set up an art academy. Vivacious in character and eloquent in speech, she made a strong impression on Matisse and became his confidante.

It was Amélie Matisse’s income as a milliner that bankrolled her husband’s financially volatile art career, and she gave up much of her time to pose for him and his friends for paintings such as his celebrated Woman with a Hat, where she’s most likely wearing one of her own creations. Though the art world frequently referred to her as Mme Matisse, emphasising this association with her husband, portraits of her by fellow Fauves André Derain, Charles Camoin and Albert Marquet testify to her significance in this moment in art history.

When the Fauves weren’t painting their wives, sex workers were a popular subject, but the choice was primarily a practicality. The artists needed nude models, and the sex workers offered a rich supply of women willing to remove their clothing for money. There were an estimated 50,000 sex workers operating in Paris at that time, most illegally. But brothel numbers were declining, and sex work was infiltrating other areas − streets, bars, hotels and cabarets and, according to letters to the police on display at the Kunstmuseum Basel, becoming a nuisance to residents of all walks of life.

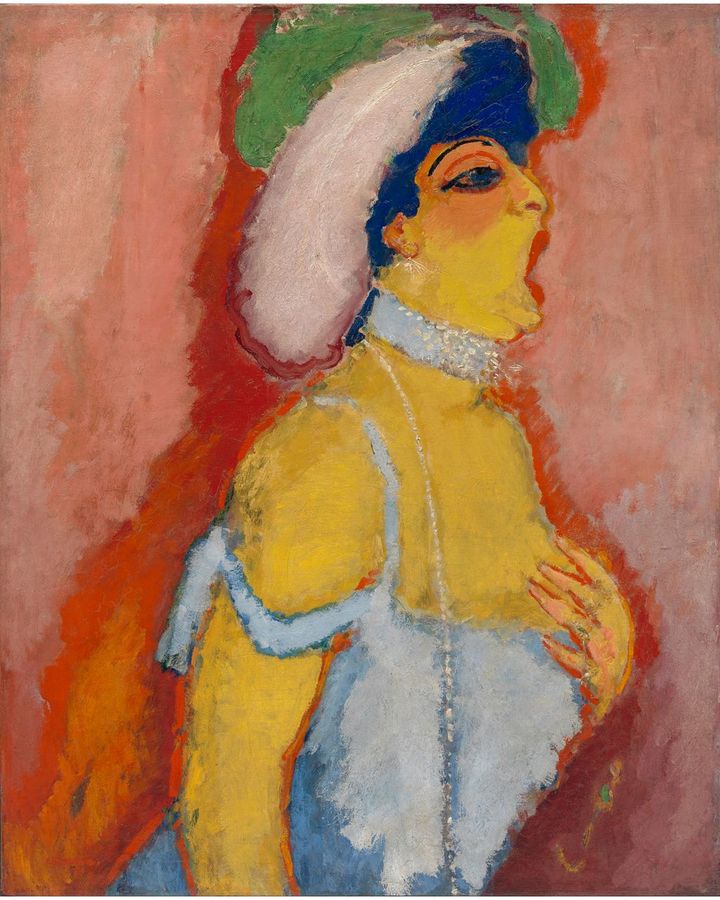

Modjesko, the Soprano Singer (1908) by Kees van Dongen (Credit: The Museum of Modern Art, New York, gift of Mr and Mrs Peter A Rübel, 1955)

Kees van Dongen was one of several Fauves to have a studio in the sex district of Montmartre, the centre of bohemian life and an ideal place to source inspiration and models. “Van Dongen had an almost carnal knowledge of the prostitution system, which he knew well from the red-light district of Rotterdam,” says historian Gabrielle Houbre, whose research in association with the Kunstmuseum Basel brings the link between sex work and Fauvism to an exhibition for the very first time.

Van Dongen’s The Hussar (1907), for example, illustrates the financial negotiations between a woman and her client, while Auguste Chabaud’s paintings, Houbre tells BBC Culture, “represent the entirety of the prostitution system” – from luxury hotels to hovels, soldiers to street walkers – with his interest becoming personal when he falls for the ebony-haired Yvette, a sex worker from society’s lower echelons.

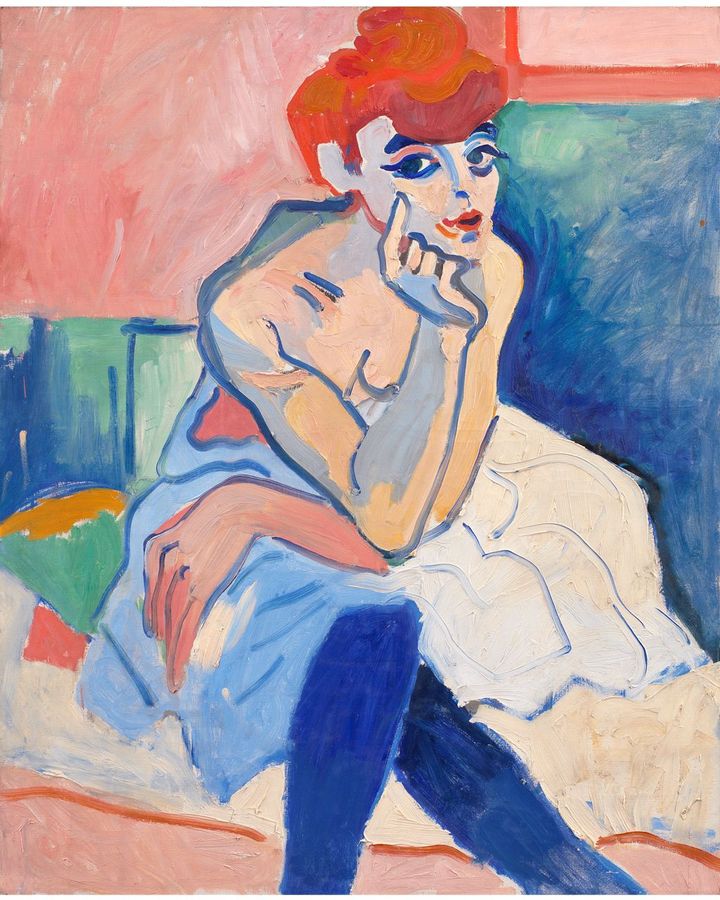

There’s an apparent disdain for the women populating Paris’s entertainment district in Maurice de Vlaminck’s early portraits, with their overly made-up, clown-like faces – grotesque dolls, it seems, for a man’s amusement. Vlaminck, who proudly admitted to painting “with my heart and my loins”, expressed his own virility on canvas in his tawdry depiction of a dancer from the Rat Mort nightclub, while Derain’s painting of the same subject, Woman in a Chemise (1906), communicates a sexual tension but is more sympathetic. This time, says Houbre, the woman “has a look about her which shows she’s no idiot”.

Woman in a Chemise (1906) by André Derain (Credit: Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen)

In some ways, the works were a form of socially acceptable erotica, sold to bourgeois men who didn’t dare participate in the lurid night life of Montmartre themselves, but were titillated by scenes of it. Made by men for men, the artworks inevitably reflected the same obsessions.

Fauvism, with its brash colours and vigorous brush work, might seem rebellious and anti-establishment, but the male artists’ portrayal of women perpetuated the same old stereotypes. “They are not the crazy anarchists that we tend to believe they are,” says Fink. “They were all petit-bourgeois, they had families, and they were members of the art committees of the time.” And since it was predominantly men both creating and buying the art, he explains, a patriarchal perspective pervaded.

There’s the trope of the female as closer to nature, for example, with pieces such as The Dance by Derain (1906) and Dance by Matisse (1909-10) ascribing women with a primitive, naïve quality. In her 1973 essay Virility and Domination in Early 20th-Century Vanguard Painting, feminist art historian Carol Duncan describes “the absoluteness with which women were pushed back to the extremity of the nature side of the dichotomy, and the insistence with which they were ranked in total opposition to all that is civilised and human”. The “beastliness” of Fauvism clearly extended to the representation of women. “A young woman has young claws, well sharpened,” Matisse once said.

But, says Fink, there’s “a clear distinction” in the way Fauves represented different women. “They depict their wives in an idolised way, in a way, morally superior. They’re dignified in their presence. Whereas, informed by late 19th-Century discourses, there’s this other extreme, where many of the portraits of the Fauves that are sexual, focus not on the face of the woman, but really on the flesh, on the genitals, on the breasts. There’s this depiction of a sexual appetite, of virility, that is not present at all in the family portraits.”

In contrast to his dressed models, Matisse’s nudes − such as Pastoral (1905) and Nude in a Forest (1906) − tend to be turned away, faceless and objectified, lacking in personality and relegated to lines and curves. Even a still life, such as Goldfish and Sculpture (1911), is a case in point. “It’s quite extreme,” agrees Fink. “The buttocks of the woman are enlarged quite significantly.” The Fauves, aware of the taboo, argued that they had a “formal” interest in women, he says. “But obviously it goes beyond that.”

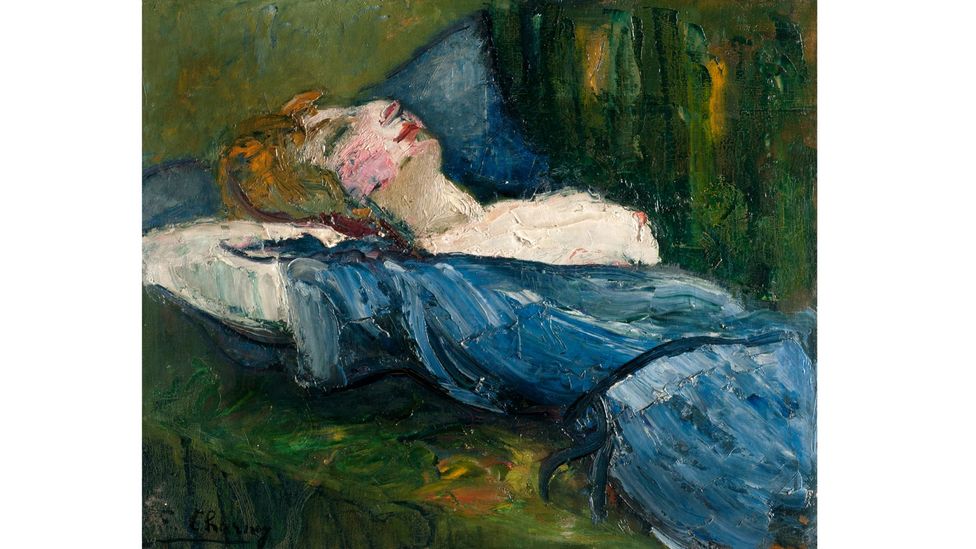

Self-portrait by Émilie Charmy (Credit: Galerie Bernard Bouche, Paris /Photo Credit: Studio GIBERT)

It took Charmy to break the mould − a rare example of a woman who frequently painted female nudes, including sex workers. “Charmy is not particularly well-known still, but deserves to be,” says Houbre. Charmy did the unthinkable: took off her own clothes, and used self-portraiture to depict women’s sexuality and desires based on her own lived experience. Divorced from the male gaze, her paintings show her enjoying her own body or in a suggested state of sexual ecstasy. “She defies the prevailing social conventions dictated by men,” Houbre continues. “For me, she’s the most audacious painter of them all.”