With its seething menace and bleak realism, punctuated by the occasional dose of the surreal, Shane Meadows’ Dead Man’s Shoes (2004) is a uniquely British story of small-town cruelty and revenge. Made on a shoestring budget with a cast of actors who would later go on to major work in Hollywood, the film, now just shy of 20 years old, has long been difficult to see, and is mercifully receiving a restoration and UK theatrical re-release today.

More like this:

– The most violent film Hitchcock ever made

– Why The Devils is still being censored

– William Friedkin’s undersung masterpiece

Meadows’ film is narratively straightforward: it stars Paddy Considine as Richard, a soldier returning to his small Derbyshire town after seven years’ absence, who wants to confront the sleazy thugs that viciously bullied his learning-disabled brother Anthony, played by Toby Kebbell.

Like other Shane Meadows’ films, Dead Man’s Shoes is set in the Midlands – in this case a depressed but picturesque Derbyshire town (Credit: Warp films)

Dead Man’s Shoes takes place far away from the well-spoken Brits of Richard Curtis romances or even the unquestioning machismo of Guy Ritchie’s Cockney gangsters. Shane Meadows provides a more grimly realistic and questioning tone to the idea of the tough-guy Brit, and takes his story north of London, crucially: something much of British cinema exported abroad fails to do.

The film is also part of a current British Film Institute season Acting Hard, exploring working-class masculinity in British films from the Thatcher era onward, and curated by filmmaker Nia Childs. BBC Culture spoke to Meadows – the one-of-a-kind progenitor of British working-class stories, best known for This is England (2006) – on the phone, while he was en route to location scout for his first potential feature film in a decade. He couldn’t say much on the details for that one, but he was more than happy to share his thoughts about his earlier modern classic. On the inspiration for Richard’s ex-soldier character, for instance, he looked to his own upbringing in the market town of Uttoxeter, Staffordshire.

“It was a mixed thing where I grew up, where some lads went into the army if they were caught fighting or thieving, almost like a last resort. I can remember a few people I grew up with where they were going into the army so they didn’t go into prison. Other lads it was more the dream of escaping the town, a geographical romance. If you factor in that industry in so many of these towns was dying, it was a more attractive proposition than staying in the same precinct for the rest of your life,” he says.

A tale of a ‘forgotten place’

Location is everything in Meadows’ work, not least because the Nottingham-based filmmaker has centred the Midlands, its dialect, and its cultural specificity in basically every way. That is particularly true for Dead Man’s Shoes: its setting in a depressed but picturesque Derbyshire town near the Peak District known as Matlock is one of the “forgotten places”, as Meadows has it.

“Everyone thinks cities are much more dangerous. But that’s not always the case, especially with bullying. In a city or larger town, it’s easier to avoid people. Where I grew up, there was one high street and one bus station, so they could be on your case for the next eight years. Matlock had all of those ingredients, and this incredible deserted building looking down on it – Riber Castle – which reminded me again of my childhood, kids playing in these old derelict abandoned buildings,” he explains of the striking setting.

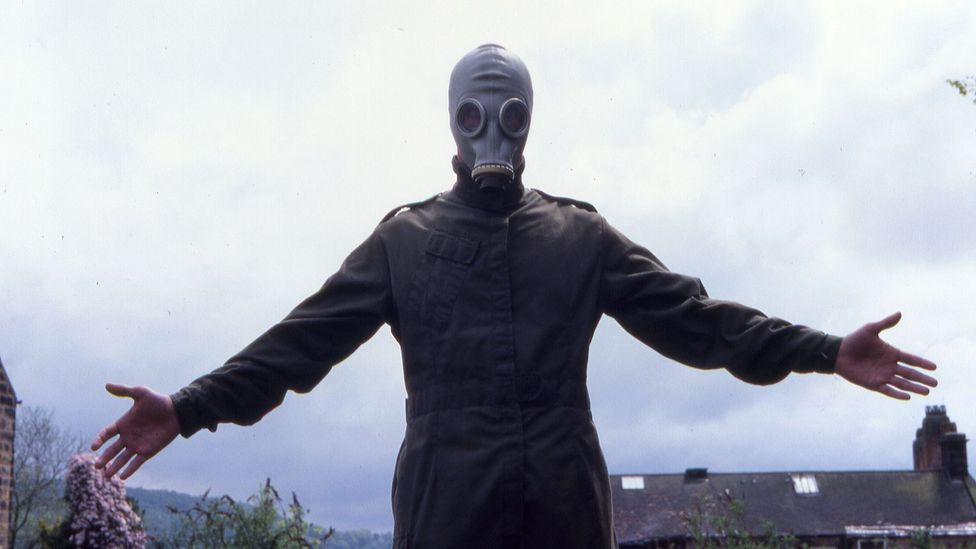

Paddy Considine’s Richard wears a gas mask to sinister effect – something the actor came up with via improvisation (Credit: Warp films)

The claustrophobia of that setting lends itself to the dread of the resulting film, with a gas-mask-donning Richard appearing like a vindictive apparition to hunt down each of the gang members. But Meadows constantly utilises black-and-white flashbacks to instances of Anthony’s bullying; he is certain to drive home precisely why this revenge is occurring. “I grew up on films like Made in Britain, by Alan Clarke. Alan Clarke’s work is the closest thing I ever saw to my life on screen. But I would say that the most putrid, the most visceral and affecting experiences of violence have always been seeing it happen in the flesh, how violence spins from nothing. It can be brewing over hours in a room, and you know something bad’s coming. Or it comes out of laughter: you think everything’s fine, and then it’s unleashed,” Meadows says. “For me, my aim has always been to show the minimum amount of violence, but the maximum impact that it can have on screen.”

There is a viscerally unpleasant quality to Dead Man’s Shoes that undergirds the director’s fascination with masculinity and violence throughout his career. Its depiction of the thugs bullying and forcing recreational drugs on the disabled Anthony – not to mention their sexual coercion of a young woman – remains incredibly difficult viewing years on. But not without rhyme or reason: this lean thriller comes deep from the psyche of small-town British meanness, where people follow the macho flock. Be that the football hooligans of Alan Clarke’s The Firm or the skins of Meadows’ own This is England, the peer pressure of masculinity is a running theme in British cinema of this kind.

“The thing I’ve always been fascinated by was that I always had to pretend to be a tougher nut than I actually was. Growing up where I grew up, by night – if you’re being bullied or people are on your case, the only way to get out of that was to attach yourself to, or pretend you were, a hard man,” Meadows says. “It’s a bizarre ranking system that goes on, where you have the whole hierarchy – to avoid the maximum amount of violence, you actually had to engage in some to be able to avoid it long term. And that can cause some quite deep wounds.”

The depictions of the increasingly paranoid gang – led by Sonny (Gary Stretch, a former boxer with no previous screen credits to his name, doing a phenomenal job as the sadistic ringleader) – are fascinatingly complex. We spend more time with their perspective than we do our protagonist, and know more about their daily rituals – hanging out, shooting up, playing cards, looking at porn, and talking rubbish – than we might otherwise with a bunch of antagonists.

“Most bullies have been bullied themselves, so I didn’t just want to whack them in as two-dimensional thugs. What they’ve done is disgusting. But at the same time: where I grew up, it was a mixed bag. You end up with mates or in these situations where you may be hanging around with people that you wouldn’t necessarily choose to later. You end up having a soft spot for them even if they’re not the nicest. So it’s never simple.”

The film spends considerable time observing the vicious gang on whom Richard is taking revenge (Credit: Warp films)

To achieve such a humane approach, Meadows filmed chronologically, encouraging improvisation in rehearsals to fully flesh out even the most diabolical of his characters. It’s how Paddy Considine ended up with a green army jacket – he wanted to pay homage to Sylvester Stallone in First Blood – and a random gas mask which helped him get into character. The results are effective. “When [one of the thugs] Herbie thinks he’s striking a deal for his life, and then he gets that awful [knifing], and you can hear the fluid dripping out from the knife wound. I was watching that live, and we weren’t quite sure how Paddy was going to play it. It was frightening. That’s almost where he’s becoming a monster himself, playing psychological games to wreak that revenge. He’s becoming like the people who did what they did to his brother.”

Reckoning with revenge

In retrospect, the film’s interest in the complexity and futility of violent revenge does feel part of a running thread in Meadows’ work. In 2019, in an interview with The Guardian before his TV series The Virtues aired, Meadows spoke for the first time about a long-repressed childhood sexual assault he experienced, an incident that haunted him, and has perhaps informed his work. The Virtues is arguably Meadows’ most mature and haunting output, and features a masterclass in performance from Stephen Graham as a man searching through the pieces of a similarly traumatic past.

When I say that rewatching Dead Man’s Shoes tale of reckoning between closure and payback drew some parallels with The Virtues, Meadows says: “I won’t go into The Virtues on a personal level too much, but, over the course of [reckoning with the assault], I had a decision to make for myself. I’m not saying it was on the scale of Dead Man’s Shoes. But there was a part of me that wanted to give someone a right good hiding. But I thought, I’ve got two choices here. And maybe the best thing I can do is use the tools that I’ve learned to use best, which is actually to make something about it, rather than try and go back to my life 20 years ago and get into an excessive sort of street fight scenario. So I’ve not got to the roots of some of those things in myself, but [with Dead Man’s Shoes] I was already kind of starting to think, well: forgiveness is the answer.”

That the men of Dead Man’s Shoes are too poisonous or blind to see that until it’s too late is undoubtedly part of the point, but there’s no judgement here. “Sometimes it wasn’t the case of wanting to be this cockfighting uber-man kind of character,” Meadows says of his rough-and-tumble past. “You were almost protecting yourself like a shield. So my interest in masculinity has always been about that complexity, and I’ve been drawn to that my whole life. There’s a grey area to it that’s about more than people just being thugs.”

Given the cultural specificity of Dead Man’s Shoes, it’s a perfect crown jewel for a film season like Acting Hard. It is not only about violence, masculinity, or revenge as free-floating academic ideas: it’s about a scenario where all of these things are inextricable from the world they emerge from, and the very act of examining them at all is a step in the right direction.