Sony

Sony

The new Blake Lively movie about a romance that turns abusive is adapted from the bestseller by New Adult phenomenon Colleen Hoover. Will it be as popular – and as divisive – as the novel?

Warning: This article contains references to domestic violence.

When the trailer for It Ends with Us dropped in May, it earned 128 million views in just 24 hours. The hullabaloo can partly be explained by the fact that the film’s co-producer and star is the talented Blake Lively, aka Taylor Swift’s friend, aka Ryan Reynolds’ wife. But it’s mostly because It Ends with Us is based on a best-selling novel by 44-year-old-Texan, Colleen Hoover, who is viewed by millions of Gen-Z women as a goddess, yet has been accused of glamorising domestic abuse.

While, for example, The Literary Vault praised the book’s “rare sensitivity and nuanced approach”, others have suggested it is much more problematic. “Like too many books and movies, It Ends with Us feeds into the very structures of toxic masculinity that it purports to combat,” Jennie Young wrote in a 2022 review of the book in Ms Magazine, and more criticism followed. Cosmopolitan said: “Colleen Hoover’s books are extremely popular and leave an impression on young women – Hoover’s primary audience – by casually portraying abuse as ‘just how a relationship is supposed to work'”.

Hoover’s humble origins are all part of her myth. In her early 30s, she was married with three children, living in a trailer in Saltillo, Texas, and struggling to pay the bills – her husband was a long-distance truck driver, she was a social worker. In 2012, she self-published her first book, a romance called Slammed. Thanks to positive reviews on Amazon, she was able to keep writing, and a few years on was then discovered by BookTok, the corner of TikTok dominated by bookworms.

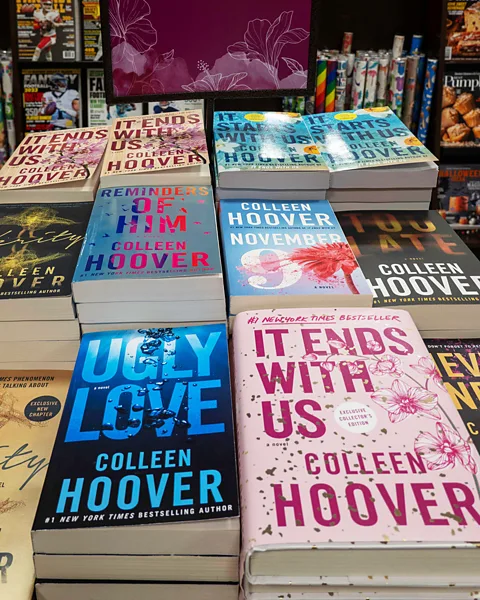

Gen Z-ers started posting videos of their happily breathless or tearful selves, during and after reading “CoHo’s” novels. These “CoHorts”, as her fans call themselves, put Hoovers back catalogue on the map, with It Ends with Us, written in 2016, at the very top of the pile. By 2022, six of Hoover’s books were on the New York Times’s paperback fiction bestseller list, and were outselling the Bible. She has published 26 fiction works in all, and this year – according to Forbes – sold 1.83 million print copies, despite having no new books on the market.

Hoover doesn’t always stick to the romance genre (she’s written mysteries and psychological thrillers, too). But her stories generally involve twists, goofy humour, a lot of euphoric sex, and her gorgeous, twentysomething female protagonists tend to have suffered in their teens and/or view themselves as dark (the heroine of It Ends with Us hits on the idea of creating an “edgy” floral shop that “caters to all the people who hate flowers”). Hoover has written about infertility, adultery, stalking, maternal filicide, fatal car-crashes, abortion and gender-based violence. Arguably, her work has a meta side: many of her central characters are published or wannabe writers, who fight for the right to let their imaginations run free. Undeniably, she’s an expert at creating young characters to whom young readers respond. The phrase “New Adult” (NA) was coined back in 2009 to describe books aimed at emerging adults (aged roughly 18 to 25), and as Hoover has said “New Adult was huge” when she began writing It Ends with Us. Suffice to say, she’s got the YA (Young Adult) and NA markets covered.

Alamy

Alamy

Molly Crawford, Editorial Director at Simon & Schuster UK and Hoover’s UK editor, says Hoover is successful because she offers “a unique experience that is hard to quantify and impossible to mimic”. It’s tempting to make a connection between Hoover and Taylor Swift, another mega-successful, female-centric, US wordsmith who offers insights into tortuous love affairs (aptly, Swift’s song, My Tears Ricochet, is used on the trailer for It Ends with Us). Crawford demurs: “I’m not sure that’s the most helpful comparison, although I’d guess there’s some overlap in their fandoms.” Asked why Hoover’s work resonates with the young, Crawford tells the BBC, “It’s an interesting phenomenon, given that Colleen’s books are intended for adult readers. I think it’s probably to do with the fact that Colleen’s novels deal with life’s big emotions and pivotal moments – something teenagers are more concerned about than most.”

Author Joanna Nadin, who has a PhD in YA literature, has a different theory. She says the attraction of Hoover’s books is that “everyone else is reading them. Teens see them on TikTok, see their friends reading them, see them in the ‘TikTok made me buy it’ section of bookshops, which really is a thing, by the way. It’s a self-fulfilling prophecy.” The books’ spicy content, Nadin tells the BBC, is another plus. “As with Virginia Andrews, whose Flowers in the Attic series is the 1980s equivalent, the books deal with taboo subjects. That appeals to teens, who are beginning to wrestle with power, test boundaries, explore the dangerous and forbidden. Add to that they’re an easy read, and it’s a great formula.”

Nadin – whose latest novel, My Teeth in Your Heart, is out now – has never read a Hoover book from beginning to end. She bought a copy of It Ends with Us (“As someone who writes for teens, it felt like a must”), but stopped reading after the first few pages, “Not because it was bad – it wasn’t, it’s compelling writing – but because I felt it wasn’t aimed at me. And fair enough, I’m 53, I’m not the target audience for New Adult.” It’s easy to mock It Ends with Us, which charts the doomed romance between heroine, Lily, and Ryle, an impulsive, possessive, increasingly violent, 28-year-old neurosurgeon. For starters, it’s not possible to be a 28-year-old neurosurgeon; how did that glaring error get past the book’s editors? Also, too many pages are devoted to cringey descriptions of how hot the perfectly toned Ryle looks in scrubs.

Getty Images

Getty Images

At the end of the book, in the Note from the Author, Hoover says she based Lily on her own mother, who left Hoover’s abusive father just before Hoover turned three. Hoover didn’t need to research this topic. Her mother lived it and, as Hoover is at pains to point out at the end of the book, “She wasn’t rescued by another man – a knight in shining armour. She took the initiative to leave my father on her own”.

Lily, as a teenager, watches her mother being abused by her father. Her mother is unable to walk away from the situation; the abuse stops only because the dad dies. As an adult, the empathetic but also insecure Lily finds herself drawn to the love-bombing, pent-up Ryle. Three months into their relationship, he is physically abusive to her, in a reworking of a scenario that had happened to Hoover’s mother. Soon, Lily finds herself thinking, “People spend so much time wondering why the women don’t leave. Where are all the people who wonder why the men are even abusive?” It’s crucial to the book’s effect that the self-deluded Ryle is a painfully human and, in many ways, sympathetic figure. You don’t want Lily to stay with Ryle; each abuse scene is more harrowing than the last. At the same time, you understand why it’s hard – emotionally and financially – for her to extricate herself from his life.

‘Text-book bad boys‘

So why is Hoover criticised for white-washing abuse? Maybe it’s because so many of the heroes in her other novels are text-book bad boys – sexily screwed-up loners who put the heroines through hell before offering the heaven of a Happily Ever After. In 2014’s Ugly Love, traumatised pilot, Miles, is sometimes sensitive but mostly “angry” and “intimidating”, a combination which heroine, Tate, finds irresistible. In Hoover’s 2015 novel November 9th, budding writer, Ben, sets fire to a car, stalks Fallon, (the victim of said fire) and fantasises about using physical force against her. In 2018’s Verity, we discover that handsome married hero, Jeremy, once tried to kill his wife. At the end of the book, he kills his wife.

True, in 2022, Hoover wrote a bonus epilogue chapter for Verity (published exclusively in the collector’s edition, but available on-line), that paints both Jeremy and the love-struck young narrator, Lowen, as unhinged. But that doesn’t cut any ice with feminist film critic, Linda Marric. “Colleen Hoover has made her name by fetishing toxic relationships,” Marric tells the BBC. “Her very young readership are growing up thinking that unacceptable behaviour, by men, is normal.” (The BBC approached Colleen Hoover’s representatives for comment.)

The new film adaptation of It Ends with Us, released in UK and US cinemas today, has also been met with mixed opinions. While The Guardian review describes it as a “glossy, and often rather graceful romantic drama”, The Telegraph says: “Blake Lively’s queasy drama repackages domestic violence as slick romance”.

There has also been criticism that the marketing for the film does not fully prepare the audience. In a comment to Metro, domestic violence charity Women’s Aid says: “It is important for popular culture to show survivors of domestic abuse they are not alone… Films like this, which depict domestic abuse, can be dangerous and retraumatising for survivors, especially if they are not expecting these themes.”

When it comes to cinematic depictions of domestic abuse, Marric says that the sanitised spectacles served up by Hollywood are insulting. “If you’ve seen abuse up close, those kinds of movies are horrible. I can’t stand Sleeping with the Enemy [the 1991 thriller, starring Julia Roberts], or Enough [with Jennifer Lopez]. All they’re offering are simplistic, cautionary tales.”

The movies that successfully explore the issue for Marric – “the films that really get it right” – are indie dramas like Gary Oldman’s 1997 film Nil by Mouth, (in which Ray Winstone’s protagonist constantly lashes out at his wife, played by Kathy Burke), or another British actor’s feature film directing debut, Paddy Considine’s 2011 effort Tyrannosaur, starring Olivia Colman. “For me,” says Marric, “Tyrannosaur was a really authentic representation of what it’s like to be abused in a relationship.”

Sony

Sony

Film critic Jonathan Romney cites There’s Still Tomorrow, an Italian period drama that was hugely popular with local audiences. “It’s a mainstream, feelgood film, with a feminist message,” Romney tells the BBC, “and what makes it interesting is its knowing attitude. The setting is 1940s Rome, and heroine, Delia, played by writer/director Paola Cortellesi, clearly doesn’t have the kind of strength we associate with Italian neo-realist icons like Anna Magnani or Silvana Mangano. She’s brutalised by her husband and patronised by her three children. She suffers for her family, yet yearns for freedom. Cleverly, the film leads us to think that freedom will come through romance and finding the right man. Yet freedom turns out to be political [the film’s climax revolves around a national referendum, the first election in which Italian women were allowed to vote].”

Romney says There’s Still Tomorrow, playfully exposes how far we haven’t come. These sort of narratives, he says, appear to serve up soothing nostalgia, only to alert us to problems in the present: “Cortellesi’s point is that gender-based violence isn’t a thing of the past.” Cortellesi, of course, is right. It’s been estimated that domestic violence impacts around 10 million people in the US, and as many as one in four women. Meanwhile, in the UK, two million women are estimated to be victims of gender-based violence each year. Police chiefs recently called the situation a “national emergency”.

The question is: for all the mixed reviews, can the film of It Ends with Us connect with mainstream audiences, and transform the kind of conversations we have about abuse? When the trailers first appeared, TikTokkers were obsessed with the casting, and it was widely felt 36-year-old Lively was too old to play Lily. Justin Baldoni, who plays Ryle and doubles as the new film’s director, is hoping what viewers take away from his movie is the realisation that “abuse happens to women of all ages… powerful women… affluent women… If a Lily walks into that theatre, and she watches this movie, will she go home and make a different choice? That’s exciting to me.”

In Hoover’s It Starts with Us, the 2022 sequel to It Ends with Us, Lily decides that anyone who’s ever left a manipulative, abusive spouse deserves a “superhero movie”. Because “it takes less strength to pick up a building than it does to permanently leave an abusive situation”.

Sony

Sony

Maybe we could think of Baldoni’s It Ends with Us as a superhero movie in disguise. This summer you can watch Deadpool (played by Ryan Reynolds) save the world. And/or you can watch Lively’s Lily Bloom save herself. What a shocking twist it would be if it was Lily’s bravery that got everyone talking. Variety says that the film is predicted to do well at the weekend in the US, with some saying it could “skyrocket to $40m to $50m”, which could put it neck to neck with Deadpool.

Meanwhile, Verity is now being adapted for the big screen. It’s also been announced that, over the next five years, Atria Books and Grant Central Publishing will publish four new Hoover novels. This author is a cheerful Cinderella, juggling many balls. For now, at least, her fans outnumber her foes, and it seems there’s no end to what she can do.

It Ends With Us is released on 9 August.

If you have experienced gender-based violence or know someone who you believe has, you can consult the UN Women’s Global Database on Violence Against Women to find a support hotline in your country, or click on this BBC Action Line if you are based in the UK.