The Austrian Symbolist painter Gustav Klimt is best-known for the immortalising opulence of such milestones of modern art as his gold-leaf-encrusted canvases The Kiss, 1907-8, and Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I, 1907. But it is a rather less famous work – one that was still sitting on the artist’s easel when Klimt died from pneumonia as a result of the flu in February 1918, a month after suffering a devastating stroke that had left him partially paralysed and unable to paint – that is expected to fetch the highest price ever paid for a painting in Europe when it is sold at auction next week

More like this:

– The tragedy of art’s greatest supermodel

– 10 artworks that caused a scandal

– The 300-year-old pet portraits

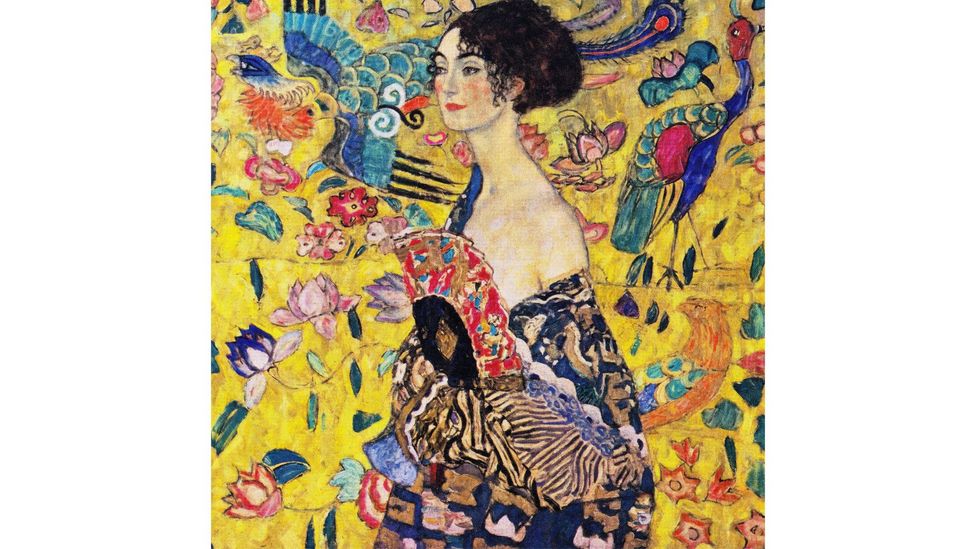

A wonder of interweaving patterns and mingled rhythms, Lady with a Fan captures a young woman lost in thought as she stands before us, staring askance into the faraway distance to our left. Her identity remains unknown. That she hasn’t noticed our intrusion into the intimate space that she inhabits, bedroom or boudoir, seems clear enough from the unheeded slip of her ornate robe down her arm and the tentative hold that her fingers have on the folding fan that shields her breasts – a perilous prop that feels a flimsy flick away from falling.

Eschewing the traditional vertical format for portraits in Lady with a Fan, Klimt used a square, giving the painting a modern edge (Credit: Alamy)

What holds us entranced by the woman’s entrancement is the carefully choreographed clash of pattern, pigment and texture that fix her in this alluringly stylised elsewhere. The work is a vibrant inventory of Klimt’s own cultural obsessions, from flowing Chinese robes to the floating lyricism of Japanese woodcuts, both of which the artist collected and turned to for inspiration. Klimt’s home, according to the Austrian expressionist Egon Schiele, whom Klimt mentored, was furnished with “a large number of Japanese prints covering the walls” and “a huge wardrobe, which held his marvellous collection of Chinese and Japanese robes”. The rich silk of the young woman’s green and gold striped robe, her porcelain complexion blushed with rouge, her chestnut curls, and the imagined flutter of the fan’s vermillion leaves, all form a riot that is invigorated further by the chaos behind her.

This flattened background, which recalls the smooth dimensionalities of Japanese woodblocks and painted Chinese porcelain, could as easily be ornate wallpaper as the immaterial fabric of the daydreaming young woman’s imagination. Here we find floating a mystical phoenix (or , a symbol of grace and virtue in Chinese mythology) with fabulous emerald fangled feathers, as if fledged from the mystery of her mind. Opposite the phoenix, standing on the right of the canvas, boasting breast feathers of resplendent ultramarine, stands a long-legged crane, an emblem of wisdom and immortality, while all around the unreal air explodes with bright bursts of pink lotus flowers, signifying the immutability of beauty.

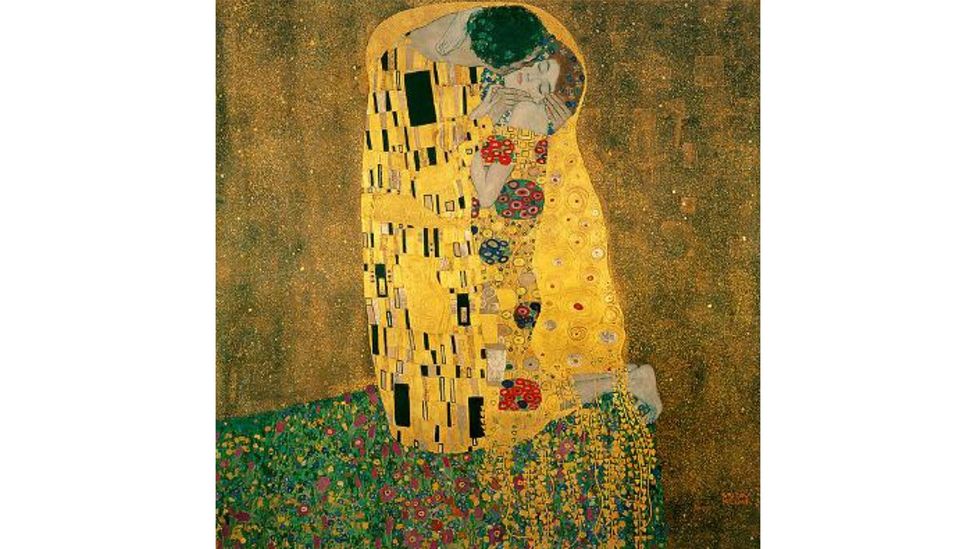

Influenced by the Art Nouveau style and painted with added gold leaf, The Kiss (1907-8) is one of Klimt’s most popular works (Credit: Alamy)

Lady with a Fan is among the very few portraits by Klimt, a leading figure of the Vienna Secession art movement, to be owned privately. It was last sold in 1994, when it fetched $11.6m (£9m). Thirty years later, it is expected to command nearly seven times that, likely becoming one of the most expensive portraits ever to come to auction. If Sotheby’s achieves the price it is asking, £65.5m ($83.4m), Klimt’s final painting will soar past René Magritte’s L’empire des Lumières, which sold for £59.4m ($75.6m) in 2022; Alberto Giacometti’s Walking Man I, which set the record for any work of art sold at auction in Europe when it went in 2010 for £65m ($83m); and Claude Monet’s Le Bassin aux Nymphéas, which sold for £40.9m ($52m) in 2008.

Set side-by-side with Klimt’s better-known works, such as The Kiss and Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I, Lady with a Fan reveals how far the artist had travelled creatively in the decade before his death. Gone is the audacious glitter of gold leaf that exalted his sensual subjects into secular icons. Far looser and more expressive in its brushstrokes, Lady with a Fan relies for its intensity on the blurring of textures, both material and psychological, as everything bleeds into a single scintillating substance. Intensifying that sense of unfixable fluidity are moments in the painting where the bare weave of linen canvas is still visible – unpainted patches that have led some to suspect that work was still unfinished. But this is a painting whose very power issues from flux and fragmentation. Its unfinishedness is what completes it.