In recent months, protesters in Russia have been arrested for holding up blank signs, giving away copies of Nineteen Eighty Four and for describing a conflict that has already killed tens of thousands of Russian soldiers as “a war”. Freedom of expression has had an elastic history in Russia. Liberties have come and gone while false dawns tease the horizon. One instance came in 1956 when Nikita Khrushchev was presiding over his first Party Congress as leader of the USSR. As the conference drew to an end, a rumour began to circulate through the convention hall. There was going to be a “closed session” later that evening. Nobody from the press or from outside the Soviet Union would be allowed to attend. When Khrushchev returned to the stage shortly after midnight, he did something nobody in Russia could have imagined witnessing for the previous three decades. He denounced Stalin.

More like this:

– The ‘dangerous’ books too powerful to read

– The radical books rewriting sex

– Why the world’s most difficult novel is so rewarding

His predecessor, Khrushchev proclaimed, had constructed an almost invincible cult of personality which he used to destroy his rivals and send legions of innocent communists to their deaths. At the height of the terror Krushchev had signed off on tens of thousands of executions at a time; had he refused, he might have been branded as an enemy of the people and thrown onto the pile. Nevertheless, his withering speech lasted for four hours with an interval and numerous interruptions as guards removed outraged hecklers from the audience. At that point, Stalin was still a secular deity, the immortal personification of Russia and the revolution. Questioning his wisdom in private, let alone in public, was to take your life in your hands.

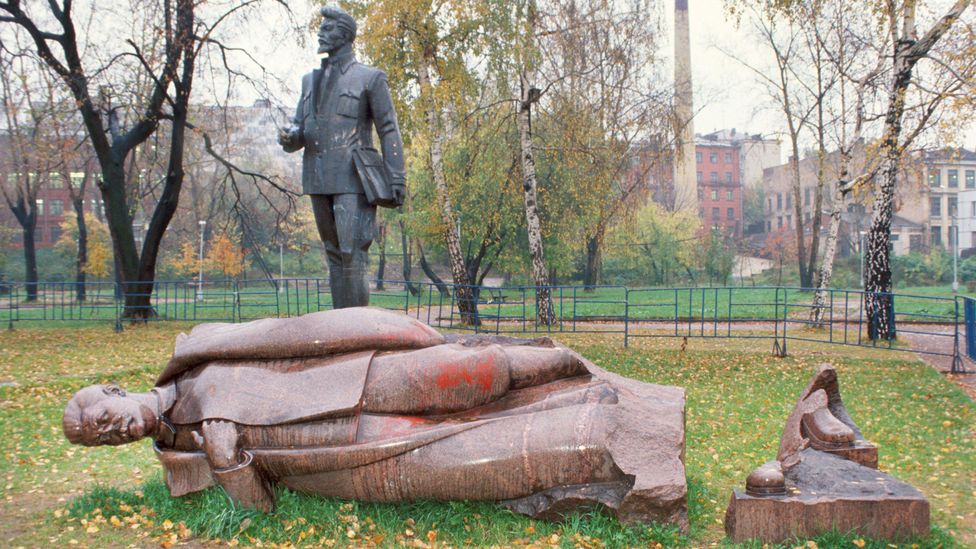

After Khrushchev’s speech, statues of Stalin were torn down (Credit: Alamy)

For Khrushchev, the immediate aim was probably to weaken his Stalinist rivals in the Politburo, but in the long run he was also trying break with totalitarianism. And while the text of the speech was considered a state secret, its consequences soon became apparent. Statues of the deceased dictator came down, political prisoners were released, Stalingrad became Volgograd and Stalino was once again Donetsk.

When he realised what was happening, the writer Vasily Grossman must have sensed an opportunity. He had been born into a Jewish family in Berdychiv, a small city to the west of Kyiv. His dad had been a Menshevik, a faction of moderate communists that had taken part in the revolution before being eradicated under Stalin. As an adult, Grossman wrote short stories while working in a coal mine in the Donbas, which would catch the attention of Maxim Gorky.

Dispatches from the frontline

In June 1941, Germany launched its ruinous invasion of the Soviet Union on a scale so large that it’s almost impossible to process. Grossman was dispatched to the frontline as a war correspondent for Krasnaya Zvezda (Red Star), an army newspaper popular among soldiers and civilians. It was rumoured that Stalin would read every page himself prior to publication. The first five months of the war saw disaster after disaster for the defenders as Germany advanced deep into Russia, capturing hundreds of thousands of Soviet troops. In the USSR, the crime of “defeatism” was often punished by death. Grossman doubtlessly saw more than he could file.

As a war correspondent for a Red Army newspaper, Grossman wrote first-hand accounts of the battles of Stalingrad, Moscow and Kursk (Credit: Alamy)

Nevertheless, he became one of the most respected journalists in the USSR. In a time of repression and paranoia, Grossman would earn the trust of his interviewees by chatting to them without a notepad. Later he would explain that he relied on “talks with a soldier withdrawn for a short break. The soldier tells you everything he has on his mind. One does not even need to ask questions.” He didn’t encourage his interviewees to repeat exaggerated acts of heroism or reiterate communist cliches for the sake of propaganda, and he didn’t do so himself either. “He was extraordinary for being a Jewish intellectual who was respected by soldiers,” says Sir Anthony Beevor, who drew heavily on Grossman’s journalism for his books about the battles for Stalingrad and Berlin. “As soon as they read his articles, they saw that he was the only one writing the truth. Grossman would visit them in their trenches and memorise everything they said.”

But he was still constrained. We can see this today in his first major novel, Stalingrad, which was published in 1952 and surgically edited to tiptoe around the cruelty and the contractions of the Red Army and was rewarded with serialisation after the war.

For Stalingrad’s sequel, the gloves would come off. During his time at the frontline, Grossman said that he could only read one book, War and Peace. When he finished, he started again. It’s clear from the size and the title of Life and Fate that Grossman wanted to honour the suffering that had surrounded him with its own classic worthy of Tolstoy. The difference was that Tolstoy hadn’t lived through Napoleon’s invasion, and his novel focused on the elites in St Petersburg and Moscow. It’s largely a tale of princes, princesses, counts, countesses, diplomats and generals. Life and Fate is a story of mothers, fathers, daughters and sons. Hitler, Eichmann and Stalin are there too, but for the most part they form an ominous backdrop, ever-present but mostly distant and always detached from the consequences of their orders.

Between the reader and the looming tyrants we find portraits of those caught in the crossfire. Short digestible chapters flicker between family dining tables, prisoner of war camps and the foxhole, where Grossman, in episode after episode, sews together the banalities and the absurdities of the eastern front. “One soldier was singing; another his eyes half-closed, was full of dire foreboding; a third was thinking about home; a forth was chewing some bread and sausage and thinking about the sausage; a fifth, his mouth wide open, was trying to identify a bird on a tree.”

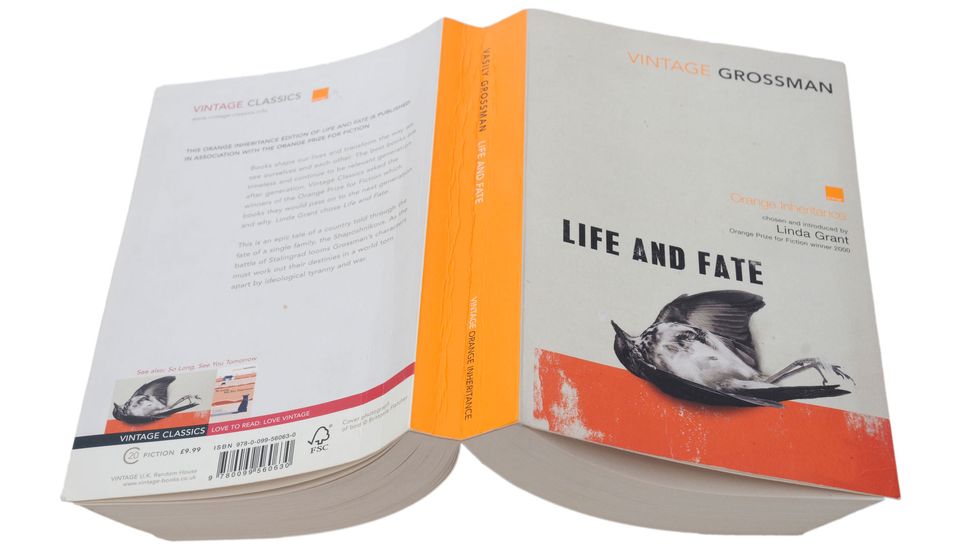

Life and Fate was the second part in a duology of novels; Stalingrad, the first, was published in 1952 (Credit: Alamy)

The result is a Bruegelian landscape divulging the grand sweep of history alongside the granular detail within. In Life and Fate, we see not just the broom but all the human dust that’s shunted along with it. Perhaps Grossman was aiming for something like War and Peace but, because of his time on the frontline, crash-landed halfway between Tolstoy’s era-defining epic and Chekhov’s timeless, microcosmic short stories. One such episode follows a young unmarried woman called Sofya as she encounters an unaccompanied little boy named David in a cramped cattle truck on its way to Auschwitz.

In 1941, Grossman’s Jewish mother had been killed by the Nazis in a mass execution in Ukraine and his reporting from the liberated death camp at Treblinka was cited as evidence at Nuremberg. Life and Fate is as much a novel about genocide as it is about war.

When they arrive, David is condemned to death. Sofya is a doctor and the Nazis are willing to spare her. She declines. Instead, Sofya goes to her death so that she can hold on to David in the gas chamber, allowing him to feel like a son and allowing her to feel like a mother.

Acts of kindness

The novel is brimming with “everyday acts of ordinary kindness that are not motivated by morality, but are motived by the moment”, says Linda Grant, a novelist who picked up Life and Fate after seeing Grossman’s name in Beevor’s footnotes. The poison turning people against each other in almost every strand of the story is ideology. Soldiers, revolutionaries and civilians alike are denounced by self-righteous Stalinists. To stay alive, they too betray the innocent. Grossman knew because it had happened to him too. He had been compromised and had compromised others, not to succeed but merely to survive. “The lesson is that you shouldn’t believe in overarching ideology,” Grant tells BBC Culture, “it’s against moral certainty.”

Grossman would have known that such a novel could never be published under Stalin, but in 1961, five years after Khrushchev’s not-so-secret speech, it must have felt like a good time to try. It was now or never. When Grossman submitted his manuscript, however, he was visited by the KGB, who ransacked his apartment, confiscating three copies of the manuscript. One would land on the desk of the party’s chief ideologue and censor, Mikhail Suslov, who is said to have summoned Grossman to his office to explain that Life and Fate was so dangerous that it couldn’t be published “for another two to three hundred years” – although this quote has been questioned by a biographer of Grossman, Yuri Bit-Yunan.

It’s often said that war involves long stretches of boredom punctuated by moments of sheer terror. Life and Fate is journalistic in style and never had a chance to be edited. Chapter after chapter gives us the day-to-day experience of life on the frontlines of totalitarianism. As the reader slowly gets to know the characters, it almost becomes comforting. But every 50 pages or so there’ll be a passage that’s utterly heartbreaking.

Khrushchev hadn’t ushered in a new openness, but his speech had inadvertently ignited a candle in the dark that burned just long enough for Life and Fate to exist. Grossman spent the last few years of his life in a state of abject depression, telling friends that his book had been “arrested”. In 1964 he died with his book behind bars. But a decade later, a copy would be smuggled out of the USSR on microfilm, and in 1988, under Mikhail Gorbachev’s policy of Glasnost, Russians and Ukrainians were finally allowed to hold Grossman’s masterpiece in their hands. Somehow truth often seems find a way of escaping the clutches of totalitarian regimes. The same can seldom be said for truthtellers.