Bradley Cooper’s biopic of Leonard Bernstein revolves around one key question: is it possible to have it all? That is, can you be a world-class classical conductor if you’re also a Broadway and Hollywood composer? Can you be accepted by the US establishment if you have a Jewish surname? Can you be happily married to a woman while having affairs with men? Another iteration of the same overarching question must have struck Cooper himself: can you be the handsome dude from The Hangover and also be taken seriously as an Oscar-worthy actor-director-writer-producer? It turns out that you can.

More like this:

– Poor Things review: ‘Emma Stone is perfectly cast’

– Ferrari is ‘stuck in the slow lane’

– Is Hollywood self-destructing?

It takes courage to premiere a film about a world-renowned, Mahler-loving composer and conductor at the Venice Film Festival just a year after the last one, Todd Field’s Tár (even if Lydia Tár was a fictional character). And it takes courage to direct a film that was due to be made, at various times, by Steven Spielberg or Martin Scorsese, both of whom stayed on as producers. But Maestro confirms what was suggested by Cooper’s directorial debut, A Star Is Born. He has sky-high ambitions, and he has the technical virtuosity and big-hearted sincerity to fulfil those ambitions with flair.

One bold aspect is that the film’s timeline spans several decades, and Cooper adjusts its style to suit the period. It begins in 1943 when the 25-year-old Bernstein is a last-minute stand-in at Carnegie Hall for the New York Philharmonic’s indisposed conductor. With no time to rehearse, he nonetheless wields the baton with such brilliance that, well, a star is born. Soon, he is busy composing the score for a musical, On the Town, and he is trading urbane quips with Felicia Montealegre (Carey Mulligan), a moneyed actress who is keen to marry him despite her knowledge of his gay relationships.

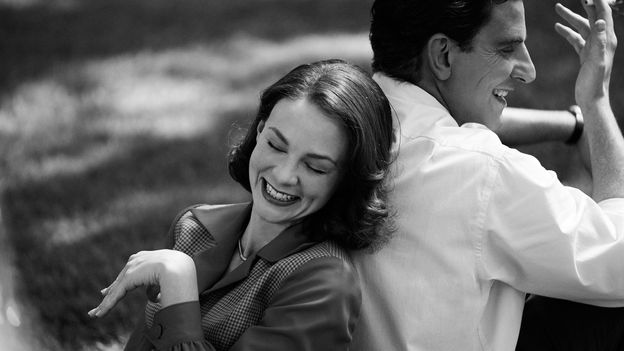

The early stages of their romance are presented as a black-and-white 1940s backstage melodrama, a whirlwind of fast talking, hectic pacing and wild dream sequences. It can be too frantic for its own good, and it doesn’t dodge every cliché of a Hollywood biopic: sometimes you’re at risk of being deafened by the clatter of all the names being dropped. (You know the kind of thing: “Hi, Jerome Robbins, I was just chatting to Aaron Copland about a lyricist called Stevie Sondheim.”) But the pastiching is done with such verve that it’s hard to resist. Later, when Bernstein is an over-stretched, over-indulged celebrity, Maestro switches to colour, and has the look and feel of a gritty 1970s drama.

The screenplay, by Cooper and Josh Singer, avoids ticking off all of Bernstein’s major triumphs and setbacks. Instead, they have constructed a fond character study that luxuriates in its subject’s livewire personality while acknowledging how exasperating and exhausting he could be. Bernstein greets the world with wide eyes and a wide grin, and conducts with such animation that he looks as if he is singing and playing every note himself. He fizzes with boyish gusto, and Cooper, in turn, doesn’t hold anything back, even when he and Bernstein are on the verge of being ridiculous and, frankly, pretty irritating. You can’t quite forget that you’re watching an actor doing an uncanny impersonation, but you never doubt that he loves the person he is playing, or that he understands Bernstein’s underlying sadness as well as his jovial brio. Maestro is a warm yet melancholy portrait of someone who is the life and soul of every party not just because he loves company but because he fears being alone.

Maestro

Director: Bradley Cooper

Cast: Bradley Cooper, Carey Mulligan, Maya Hawke, Sarah Silverman, Matt Bomer

Run time: 2hrs 9min

There is one obvious problem, though. Cooper has been criticised for wearing a prosthetic nose, a contentious choice for a non-Jewish actor playing a Jewish character. Personally, I’d argue that prosthetic noses are so distracting on the big screen that they should never be used unless someone is playing either Pinocchio or Cyrano de Bergerac. But the make-up artist, Kazu Hiro, does such an expert job that it’s easy to forget that the nose isn’t Cooper’s own. And when the elderly Bernstein talks to interviewers in the film’s framing scenes, he has some of the best old-age make-up I’ve ever seen.

Still, Maestro is not just the Bradley Cooper show. In the credits he takes second billing, ceding the top spot to Mulligan. The choice doesn’t really make sense: Bernstein is undoubtedly the central character. But Mulligan’s performance as the loyal but tortured Felicia is a sparkling tour de force, especially in the lengthy, complicated scenes in which the dialogue overlaps with documentary-like naturalism, but is also enunciated with the precision of the most sophisticated screwball comedy. She has never been better. Apparently there is some debate as to whether a woman should be addressed as a “Maestro” or a “Maestra”, but whichever term you prefer, Mulligan definitely qualifies.

★★★★☆