At Studio Morra, Naples in 1974, for six hours, it was possible to be in the same room as Marina Abramović. Of course, the performance artist has occupied many rooms since, but this was room – the most notorious one, the site of her work Rhythm 0, in which she stood completely still and invited the audience to do what they wanted to her using any of 72 items laid out for them.

“I am the object. During this period I take full responsibility,” was the instruction. All her clothes were removed from her with razor blades, and a man forced her to press a loaded gun to her neck. The next morning a clump of the artist’s hair had turned grey.

More like this:

– The artist whose naked body was a canvas

– 10 artworks that caused a scandal

– The man hunting down dead celebrities

This might be Abramović’s best-known work, but an infinitesimal number of people familiar with her today experienced it. It has been described over and over again, including by Abramović herself in her 2016 memoir Walk Through Walls and her new Visual Biography co-written with Katya Tylevich. There are photographs of the piece, showing Abramović transitioning from clean, clothed statue to vandalised, dirtied nude.

Marina Abramović at London’s Southbank Centre, where she is doing a ‘takeover’ with her performance art institute (Credit: Javier Hirschfeld)

These images are projected in a gallery room at the current Marina Abramović retrospective at London’s Royal Academy. The question of how to display Rhythm 0 was first resolved, at least to an extent, in 2010 for a similar exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York – to show these photographs around a long table, altar-like at the head of the room, with the 72 objects offered to those original viewers in 1974 to use on the artist’s body. Lipstick, feather, cotton, flowers, chains, nails, honey, saw, gun, bullet… To see those objects, laid out in tangible space, is to accept a challenge – what would you do?

These implements are once again laid out at the Royal Academy. But the photographs of Abramović being played with, doll-like, by her audience lack impact. Be it via Yoko Ono, who invited people to cut off her clothing ten years earlier, the works of her contemporary pioneers Carolee Schneemann and Ana Mendieta, or Abramović’s own 50-plus-year career, there is an extent to which audiences have been desensitised to the impact of such work – we have become accustomed in our culture to displays of violence and cruelty. Or rather, the distance created by photographic documentation has made it easier to consume such works, because no gallery would allow Rhythm 0 to be performed within its walls today. The artist might claim to take responsibility in the piece, but that can never be true.

While one can watch films of many of Abramović’s 1970s performances, to engage with her retrospective is to accept the ephemerality of her art. Abramović writes in her memoir that she loved a quote from fellow performance art pioneer Yves Klein: “My paintings are but ashes of my art.” But there is still a need for legacy, longevity, and perhaps even notoriety for the artist. Sitting in a Claridge’s suite, Abramović tells BBC Culture, “It’s really difficult to make the work presentable in a way that isn’t dated. Some of the works have this energy that has survived time. I was always interested in documentation and how to present the work for a future when I’m not there or nothing is left.”

Marina Abramović performing her 1974 piece Rhythm 0, at the most extreme end of her work (Credit: Marina Abramović/Donatelli Sbarra)

Part of that energy exists within Abramović herself. From 14 March until 31 May 2010, for 736 hours and 30 minutes, Abramović sat at a table in the middle of the MoMA retrospective of her work with visitors invited to sit opposite her, in silence. She carries her work within herself – The Artist is Present, as that piece was called, but so is the art. But she won’t be appearing in the Royal Academy retrospective. “I’m not going there because people will want to take a selfie with me. They are there to see the work, not me.” There is a distinction then between being with Abramović when she is performing and when she is not. At least, in her own self-perception. Unlike the MoMa exhibition, by removing herself entirely from the Royal Academy retrospective, Abramović is wondering whether the works survive on their own without her physical presence.

How she’s sealing her legacy

An interesting dichotomy is being created across cultural spaces while Abramović is in London. While her own works are shown at the Royal Academy, the Marina Abramović Institute (MAI), which she created in 2007 to aid the development of performance art, is this week staging a “takeover” across the Thames at the Southbank Centre. “The problem that we always face is how to present new work without attaching my name to it,” she says. “I hope that this is only temporary because once these people prove themselves, then I don’t need to be there. I need to remove myself. I become an obstacle to my own work.” That new work is to raise a generation of performance artists capable of performing long durational pieces which speak to their personal motivations. Her aims are global, staging collective performances all over the world, and for this show she has selected 11 artists from South America, Europe, America, and Asia. While Abramović will be on hand at the start and end of the takeover to introduce the audience to the work, in between she will leave her artists to speak for themselves.

In 1973, Abramović performed Rhythm 10 at the Edinburgh Festival. Adapting a Slavic game in which the player stabs a knife between their fingers, taking a drink each time they cut themselves, Abramović used ten knives and two tape machines to perform and record the dangerous feat until she had wounded herself ten times. She then stopped, replayed the recording, and attempted to reproduce the exact same rhythms and pattern of mistakes she’d made the first time.

In Walk Through Walls, Abramović remembers, “The sense of danger in the room had united the onlookers and me in that moment: the here and now, and nowhere else”. At the Royal Academy retrospective, the work is displayed as a long series of photographic stills, with the sound recording played from a speaker in the corner of the room. It is a work that plays on the nature of reperformance, of the attempt to recreate but never being capable of hitting the exact same beats. The uniqueness of the moment of artistic creation being art itself.

Discussing her 1970s works, Abramović concedes that such work could not be performed now. “Your freedom is limited by this,” she says, “and then you are so worried about what you say, to not be crucified.” It seems to Abramović that the climate of hostile response to her works has worsened since her early career, moving beyond restrictions placed by artistic spaces to a general culture that does not allow for performative risk. When Abramović started to develop her art, danger was imperative. But as she matured, she realised that art did not have to be ugly or scary in order to have meaning.

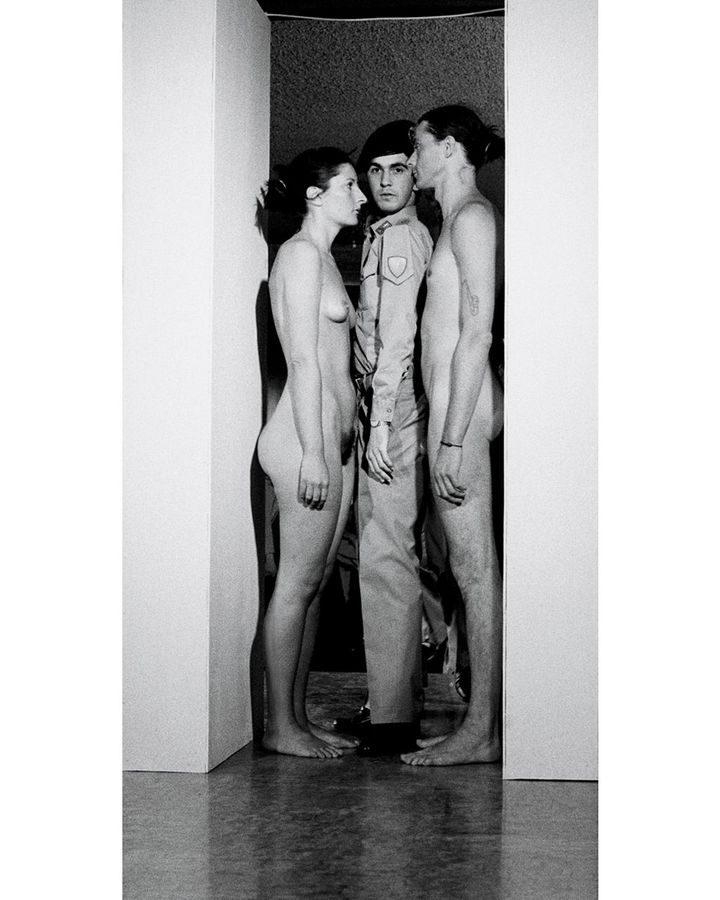

Marina Abramović’s 1977 work Imponderabilia saw her and partner Ulay stand naked as an “entrance” to the gallery (Credit: Marina Abramović Archives/ Ulay / Marina Abramović)

One of the new generation of artists performing at the MAI Takeover is Cassils, a transgender artist who uses the material of their body to explore the physical fluidity of gender. Their performance, Tiresias, sees them melt neoclassical Greek male torsos carved out of ice with their body heat. Asked about the role of danger in performance art, Cassils tells BBC Culture that it is a misconception that performance must involve physical risk. “I conduct research, consult with experts and undergo training regimes to understand the limitations of my body,” they say. “My practice is about fostering a deep somatic connection so that I may respect, deepen and care for my vessel. As we are in an increased time of oppression and violence this attunement is paramount.”

Why she’s still causing a storm

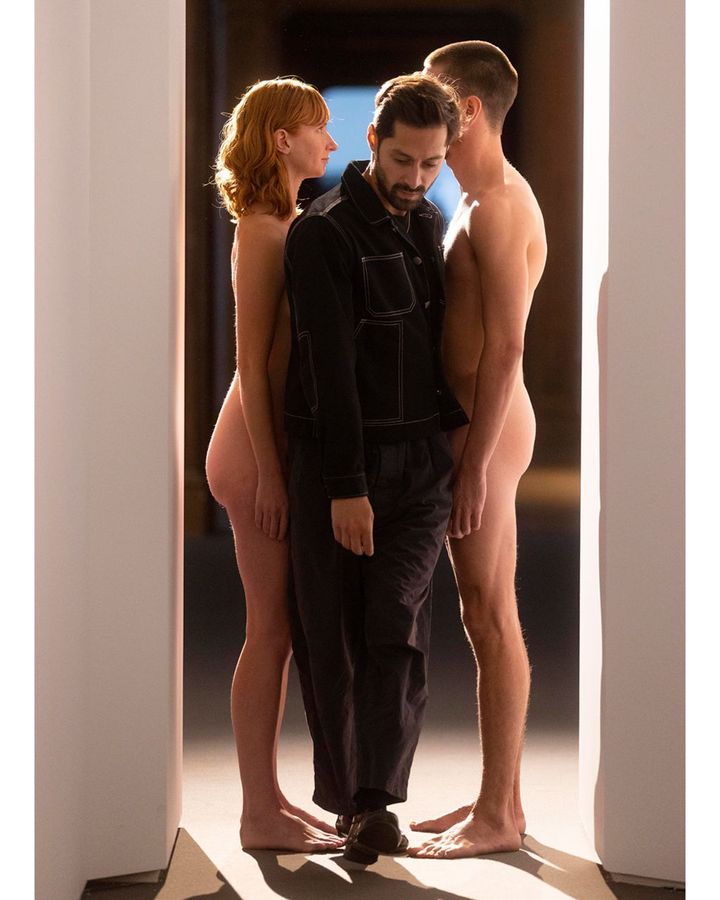

This seems to be in tune with the turn that Abramović has taken in her own works, that there are forms of response and meditation in performance art beyond sharp shocks. That is not to say that the art should not be controversial. In 1977, Abramović and her partner Ulay stood naked in a narrow doorway to become the entrance to the Galleria Comunale d’Arte Moderna, Bologna. The text next to them read: “Imponderable. Such imponderable human factors as one’s aesthetic sensitivity. The overriding importance of imponderables determining human conduct.” Entitled Imponderabilia, the piece forced the visitor to make countless decisions about how to navigate this socially undesirable situation to which there can be no right answer. The piece has been restaged at the RA, with a pair of nude performers replacing Abramović and Ulay, and almost as many protocols as there are imponderables, including security guards, restrictions on photography, psychiatric support for the artists, and so on.

Yet despite the protective measures in place, Imponderabilia has once again caused a storm. “The British audience is so puritan,” Abramović says, responding to the controversy of having real nude figures in the exhibition. “It’s so interesting that it is the same question I have been asked over and over again after 55 years of my career. Why is this art, and why is there nudity? I will never get used to it.” She is pleased at least that nobody is indifferent, and that it prompts so many responses in people who experience it. “I have always said that the public complete the work. You should never say everything.” It seems that after Abramović and the first generation of performance artists broke the rules and taboos of the art world in the 1970s, they have been rebuilt with more resolute prudishness.

It is also true that long durational performance art has largely vanished from public gallery spaces, at least in the UK. The MAI Takeover at the Southbank Centre, filling the spaces of the Queen Elizabeth Hall, including changing rooms, courtyards, and underground spaces usually closed off to the public, will be a totally new experience for a younger generation of visitors. Brazilian artist Paula Garcia tells BBC Culture that this is why a sense of danger and unpredictability still has a vital place in performance. “They both trigger a change of state,” she says, “It is as if the body, at that moment in action, manages to break out of inertia.”

The retrospective at London’s Royal Academy recreates Imponderabilia with two younger performers – and has created a storm (Credit: Royal Academy of Arts/David Parry)

Garcia’s piece, Noise Body – It’s Not Done Yet, promises to rupture the traditional, static nature of art by inviting her audience to cover her body with industrial iron scraps that will attach through magnets. “The sound of nails being thrown at a body covered by magnets is a powerful reminder of danger,” she says. “People close to the work feel the sensation of sound in their body, so it is as if the action is happening directly to them.” As with many performance pieces, including those staged by Abramović, Noise Body explores the radical freedom of the body through art, one that Garcia believes many of us have forgotten.

Each work in the takeover will respond to the specific space in which it is being staged. This is particularly the case for Sandra Johnston, whose practice is rooted in processes of improvisation. The piece she will perform, Shutter, unfolds across the five days of the takeover, with the title referring to the structures called shutters upon which the support columns of the Queen Elizabeth Hall were constructed. Reflecting on the basement space in which she will work, Johnston tells BBC Culture, “The experience is shaped by how each of us individually understands the space”. She describes the “collision” between the artist’s expectations and the actual encounter with the audience as being the space in which art exists.

Her vision for art galleries

The diversity of Abramović’s curation for the takeover reflects her vision for the future of artistic spaces. She quotes museum director and art historian Alexander Dorner (1893-1957): “The new type of art institute cannot merely be an art museum as it has been until now, but no museum at all. The new type will be more like a power station, a producer of new energy.” It is this energy that she now wants to harness and make accessible on an unprecedented scale. The museum, she says, “is not a place where you reflect on what’s happened in the past, but what is now.”

This relationship between art and audience has been central to Abramović’s work. The practice might be called “long durational performance”, but really it is a fleeting thing – something that changes in nature with every passing second, never to be regained. Most people familiar with Abramović have never been in the same room as her, let alone experienced the original staging of the works they know her for. There is a contradiction at play – Abramović has put performance art in the mainstream without most of those people ever having actually been a part of that art.

Abramović is helping a new generation of performance artists flourish (Credit: Javier Hirschfeld)

“This is why it’s incredibly important for me to help the younger generation,” she concludes. “They don’t need to go through hell like I did. I have the knowledge and I have so much experience that I can help them. We find the venues, we show different artists, different works in different countries. And once they get a reputation, they can start living out of their work.” It is interesting that restaging Abramović’s own works still has the power to inspire strong reactions, as shown by the Royal Academy retrospective, but the real force maintaining the unpredictability of performance art are the artists appearing at the Southbank Centre simultaneously. They gesture towards an uncertain future for art, but that’s what keeps it alive.

To end, Abramović stresses that not all performance art must be serious. Humour too is vital, so she wants to tell a joke: “How long do you need to fix a lightbulb in a performance context? I don’t know, I was only there for six hours.”