Nigeria, Africa’s most populous country and home of the continent’s biggest democracy, is set to select a new leader in a few days. After the #EndSARS peaceful protests that were quelled by the shooting of young protesters in October 2020, a revolutionary spirit lingers in the air. For this election, Nigerian youths have come forward to register to vote en masse, making up nearly 40% of the total. It’s a collective defiance that finds its voice in one of the most charged songs by Nigeria’s legendary activist and musician, Fela Kuti, the father of Afrobeat.

More like this:

– The exhilarating songs of street protests

– How Afrobeat was formed

– The song that changed the US

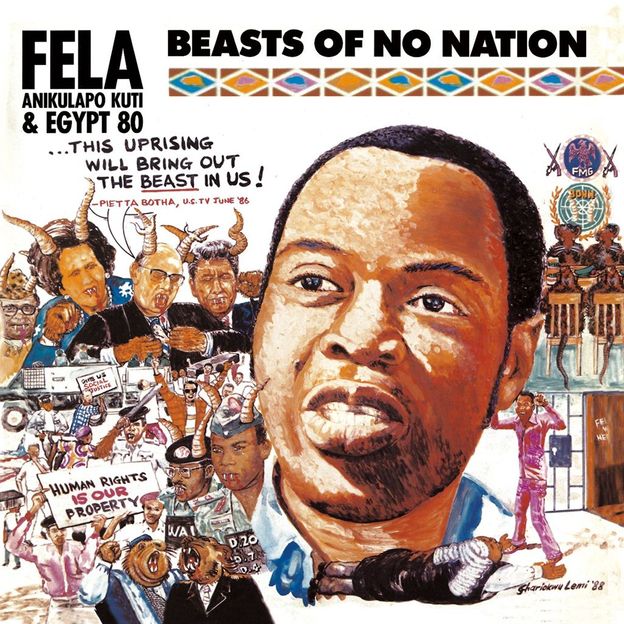

In 1986, Kuti could not wait to get Beasts of No Nation off his chest. He had been in jail for 20 months, held on charges of unlawful possession of foreign currency – according to the official statement. But he always insisted that he had been unjustly incarcerated for politically motivated reasons. While in prison, he began thinking of a song that would arguably become his most political.

“Beasts of No Nation would, no doubt, pass as one of Fela’s most defining albums in the course of four decades in terms of its scathing exposé on discordant global issues of the time,” writes Raheem Oluwafunminiyi, an academic at Osun State University. “No African artist of his generation had more artistry, deep knowledge and understanding of global politics than Fela, who used trends in both national and global discourse to name album or track titles, album jackets or poke fun at institutions, political and private figures.”

Kuti was known as an incredible performer; Paul McCartney said that he and Africa 70 ‘were the best band I’ve ever seen live’ (Credit: Getty Images)

Kuti was not a messenger the Nigerian government would have chosen to present to the world, visually or lyrically. Shirtless, with zoot (joint) in hand, and chalk decoratively marking his face and body, Fela was a living, wriggling thorn beneath the flesh of corrupt politicians and repressive military heads of state who deposed democratically elected civilian governments with a pretext of ending the widespread corruption in the country. Nigeria’s current president, Muhammadu Buhari, one of the political figures Kuti mentions in Beasts of No Nation, was the country’s military head of state from December 1983 to August 1985, after taking power in a coup d’etat.

“Fela first started singing Beasts of No Nation around 1986… He was arrested at the airport as he was about to go overseas to play on tour. There was widespread disenchantment with the governance of the country, corruption was still rampant, and beyond Nigeria, there were violent protests in South Africa against apartheid. Even the cover of the album shows these anxieties,” Nigerian writer Ikhide Ikheloa, who was a youth when Kuti first sang Beasts of No Nation, tells BBC Culture.

Kuti denounced the colonial and Eurocentric framework that he claimed African leaders adopted, and rejected what he perceived as the corrupt and oppressive political cycle. And he did this openly, through his lyrics. In his 1977 song Fear Not For Man, Kuti wrote “the father of Pan-Africanism Dr Kwame Nkrumah says to all black people all over the world:

‘The secret of life is to have no fear'” – cowering in the face of repression was a posture he was not ready to take with his craft.

Family history

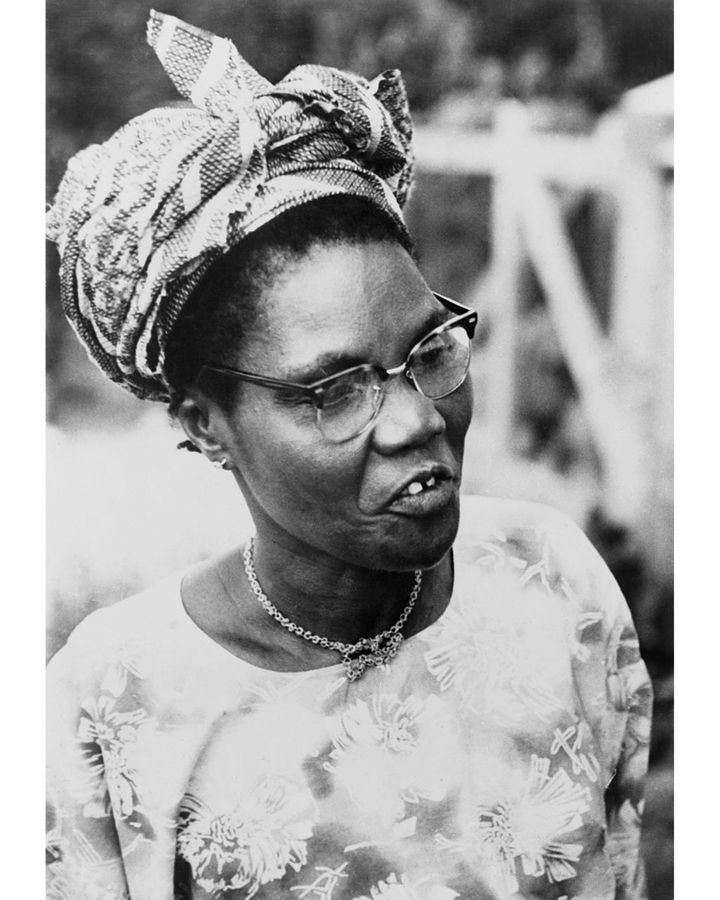

Kuti’s stand against corruption came naturally; his parents were activists who fought against colonialism and oppression. Fela’s father, Israel Ransome-Kuti, was an Anglican reverend and a unionist. His mother, Chief Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti, was a suffragist who fought for Nigerian women’s rights to vote under colonial rule. At the end of Nigeria’s colonial era in 1960, Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti helped unionise Nigerian women of different classes to demand tax cuts and better conditions for women.

Kuti’s mother, Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti, was a womens’ rights activist (Credit: Alamy)

From them, Olufela Ransome-Kuti, better known by his chosen name Fela Aníkúlápó Kuti, learnt to demand more, creating a discography of protest and opposition to oppression. Beasts of No Nation has all the ingredients that make a hit Fela record – the intoxicating, almost overpowering blasts of trumpets, sax, and horns in a cantankerous marriage with drums, guitar, and pianos that come together in the end, going on for minutes before the singing finally enters; the instrumental then makes way for the punned satire – in this case a quote from the South African president PW Botha – with which Fela indicts.

“This uprising will bring out the beast in us!” Fela screeches as he contorts himself into dance positions that bring to mind a possessed person undergoing exorcism of whatever holds them captive. And that was what it was, a kind of supernatural possession that he could neither escape nor prevent himself from responding to – the repeated arrests, or the military throwing his 77-year-old mother from the second-floor window of his home, causing injuries that led to her death 14 months later, could not stop him. It had him screaming unintelligible incantation-like chants spasmodically at the end of records and performances, either because there was more musical energy in him than he could put into actual lyrics or because he was simply no longer in control at such moments of creative release.

Aside from craftily quoting Botha, Fela points out in different parts of the song that different leaders are nothing but animals in human skin: “animal he wear represented Nigerian leaders who had come to favour the Yoruba outfit that is made with over six yards of clothing and drapes over the wearer like an extravagantly large priestly vestment. Before he wraps up the song, he names political leaders of the era – Buhari, Botha, Reagan, and Thatcher.

“Fela has this charming pedestrianism that unfailingly cloaks gleaming deconstructive spikes,” Tejumola Olaniyan writes in Arrest The Music!: Fela and his Rebel Art and Politics. “With it,” he continues, “[Fela] verbally caresses all the pet and well-embroidered foreign-policy commitments of successive Nigerian governments and completely perforates them, making them look ridiculous to the people.” Kuti goes on to criticise the United Nations for their inaction in the face of South Africa’s apartheid regime, arguing that the imbalance of the voting power of member states means that they can never really be “united”.

This global callout had the desired effect on his listeners. “Whatever came out of his lips and instruments was well received. He had the same force of reach as today’s social media. He was a powerful communicator, and the rulers knew it. He was literally a man of the people, especially among youths,” says Ikheloa. “Fela’s songs had a revolutionary fervour that resonated with everyone whenever they played. His songs remain evergreen, especially in Nigeria today, where nothing much has changed. He was a great pan-Africanist who knew how to use the power of his voice to start conversations.”

Afrobeat lives on

Kuti’s place as “The Father of Afrobeat” was not just handed to him just because he coined the word. He earned his place with sweat, blood, rigorous practice, and jail time. Through these arrests – some 200 or more – his fans, the Nigerian public, waited faithfully for him. Kuti is the father of Afrobeat because he sang it for over 20 years until it became a global sensation. He earned his place and title.

Beasts of No Nation was released in 1989 with two tracks, the title track as well as one called Just Like That (Credit: Shanachie Records /cover design: Lemi Ghariokwu)

What he started from nothing, with no blueprint – the fusion of consciousness, politics, sax, drums, spirituality, sexuality, activism, authenticity, Africanness, family, and music – has gone through sonic shape-shifting over the years in the custody of the likes of Kuti’s son Femi, as well as the singer’s protégé, Lagbaja, and countless others, to birth what today the world knows and enjoys as Afrobeats (a fusion of sounds coming out of West Africa).

In what can be called a musical sacrament – an audio grace with a spiritual power – contemporary African musicians pick up an original Kuti record and sample it in an Afrobeats track. This marriage of records across generational lines produces sounds that are as relevant today as Kuti’s songs were 30 years ago. In an Afrobeats song sampling Kuti’s Afrobeat music, listeners today find a tune that lets them dance while being politically conscious. They also find themselves overcome, feeling as though their wait is over. Many years after Kuti’s guttural singing owned stages around the world, the thirst to hear the lone voice of a musician call out the politics of the day is still quenched by him.