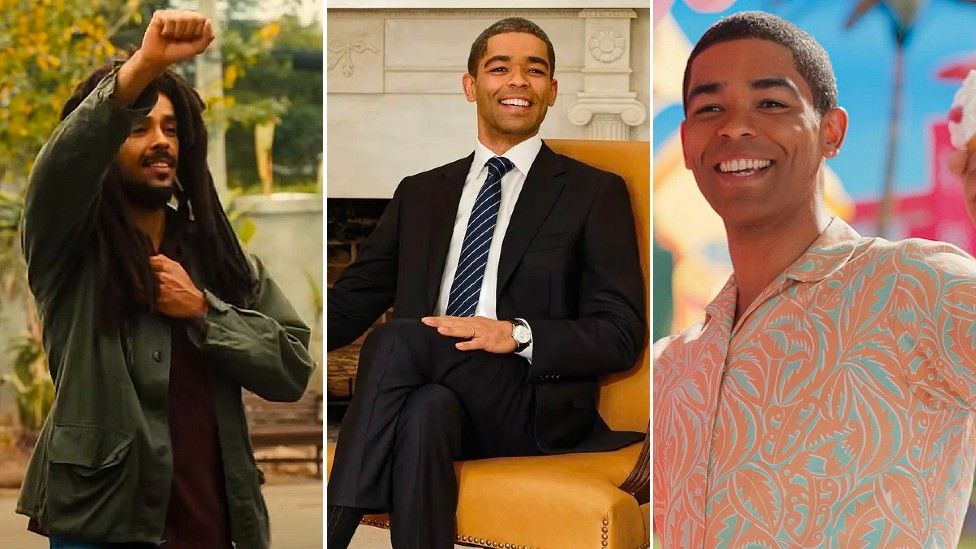

Actor Kingsley Ben-Adir knows what its like to play an iconic black leader.

In the last four years, he has portrayed former US president Barack Obama in The Comey Rule and civil rights activist Malcolm X in One Night In Miami.

But even for him, the prospect of becoming Bob Marley was daunting.

“You can’t mimic him, you can’t copy him, you can’t choreograph him,” says the 37-year-old. “It’s just not possible. It’s too spontaneous.”

So when the opportunity first arose, he turned it down. The weight and the risk simply felt too big.

“It’s a heavy burden and a very serious role,” agrees Ziggy Marley, Bob’s son and one of the custodians of his legacy.

“You look and you say, ‘Who can hold this?'”

The search took more than 30 years. Martin Scorsese and Oliver Stone were among the directors who tried, and failed, to bring the reggae legend to the big screen.

His widow, Rita, also came close. Miramax snapped up the rights to her autobiography in 2008, and Rita told reporters she wanted Lauryn Hill to play her, but the project never got off the ground.

The man who finally made it happen is Reinaldo Marcus Green. He was approached by Paramount Studios while editing King Richard – the Oscar-winning drama about the father of tennis legends Venus and Serena Williams – and instantly felt a connection to the material.

What hooked him was the story. Instead of a traditional cradle-to-grave biopic, this film would be devoted to a single, two-year timespan.

It opens in 1976, when Marley was already a star and Jamaica was in political turmoil. A wave of political shootings and firebombings rocked Kingston, as rivalries between the two major political parties spilled onto the streets.

Although Marley tried to remain neutral, he angered both sides when he organised a concert for peace.

Two days before the show, seven armed gunmen stormed into the star’s “safe house” at 56 Hope Road as he rehearsed with his band. Rita Marley was shot in the head. A bullet aimed at Bob’s chest missed and lodged in his arm.

Miraculously, both survived. But soon afterwards, the singer exiled himself in London, where he poured his feelings of betrayal, anger and ultimately hope into a new album, Exodus.

Released in 1977, it contains many of his best-loved hits: Jamming, Three Little Birds, One Love/People Get Ready and the evocative title track.

A landmark not just for reggae but for rock and roll, it was crowned “the best album of the 20th Century” by Time Magazine.

“Exodus is a ground-breaking innovative record,” says Ziggy Marley. “The open-mindedness of the record is who Bob was.”

“It was a critical time for him, rich in character and history,” says Green. “By focusing on that, we get to shine some light into the man he was.”

The human element was important, he adds, because Marley has become “such a God” that it’s hard to imagine him struggling with things like identity, paranoia and the responsibilities of fame.

“To get a sneak peek into that – who he was, how he thought – it’s pretty incredible.”

A Bob Station in Barbie-land

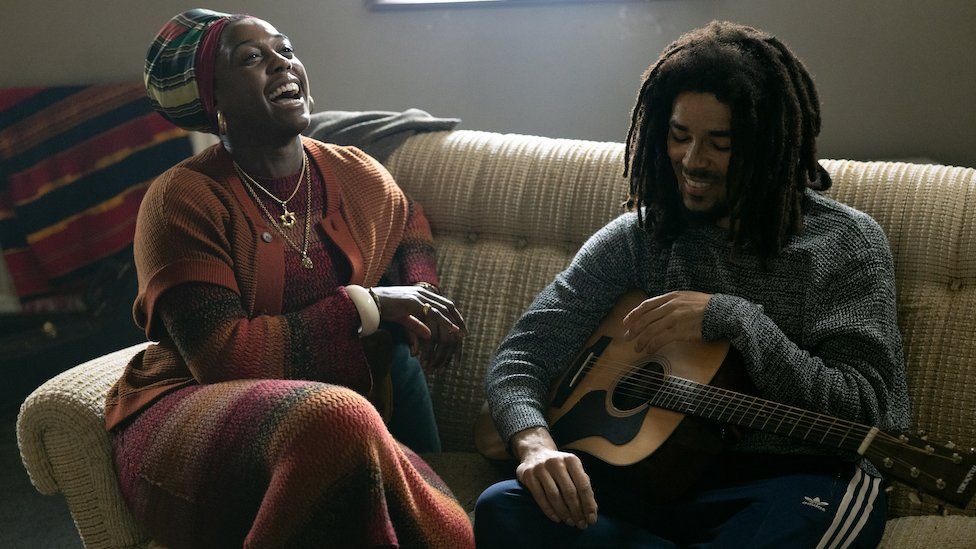

Ben-Adir thought so, too. When he read the script for One Love, he abandoned his fears and sent in a blind audition.

“It was the first tape where I thought, ‘Wow, what presence’,” says Green.

“His face, his eyes said so much behind the lens. I instantly knew we had the foundation to build something.”

There was one problem: Ben-Adir didn’t sing or dance, and he couldn’t play guitar. And when he accepted the role, he only had 10 weeks to prepare.

At the time, he was on the set of the Barbie movie in Leavesden, playing Basketball Ken. He asked director Greta Gerwig for permission to study during breaks – and she built him “a ‘Bob Station’ in Barbie-land, right behind the Mojo Dojo Casa”.

It was as surreal as it sounds. One minute, Ben-Adir would be prancing around to I’m Just Ken, the next he’d be hunched over in his paisley shirt, studying the cadences of Redemption Song.

“I was full of nervous energy and wanting to get straight to work,” he says.

Thankfully, filming got pushed back from June to December, giving Ben-Adir extra time to prepare.

“Looking back, the time-scale was not realistic,” he says. “Just the language and the patois needed such a huge amount of attention that a June start date was never going to happen.”

The patois was crucial. The Marley family wanted the film to be as authentic as possible; and that meant leaning into the musician’s Trench Town dialect.

Ben-Adir studied hours of archive interviews and unreleased recordings, reciting what he heard, then working with a team of specialists to translate the script from its original English.

“I don’t want the audience to feel like they understand everything I’m saying, because that’s not truthful,” says the actor.

“If you listen to Bob for two hours, you won’t understand everything he’s saying unless you’re Jamaican. Even I didn’t understand everything he was saying!

“So that was where Rei[naldo] and I had a really interesting dance to figure out – because we need you to understand the emotion of the story, but you’re not supposed to understand all the language.”

An early edit of the movie seen by the BBC suggests viewers won’t need subtitles, but the slang adds an extra level of immersion.

And Ben-Adir didn’t just stop at the voice. He studied hours of concert footage and learned guitar from scratch, playing “until his fingers were bleeding”, says Green.

At one point, the actor even tried writing songs of his own, just to know what it felt like.

“They were so bad!” he laughs. “I just was like, ‘God, I wouldn’t sing this to anyone. It’s so cringe.’

“But the point is not that I’m terrible songwriter – it’s that what became clearer and clearer to me was the genius of Bob’s music, and how committed he was.

“You know, he was really competitive. He’d be up at four or five in the morning with the guitar. And he liked the sound of his voice at that time of the day, because there was a roughness to it.

“So he’d play all day, break for football, then work until two in the morning in the studio. He didn’t mess around.”

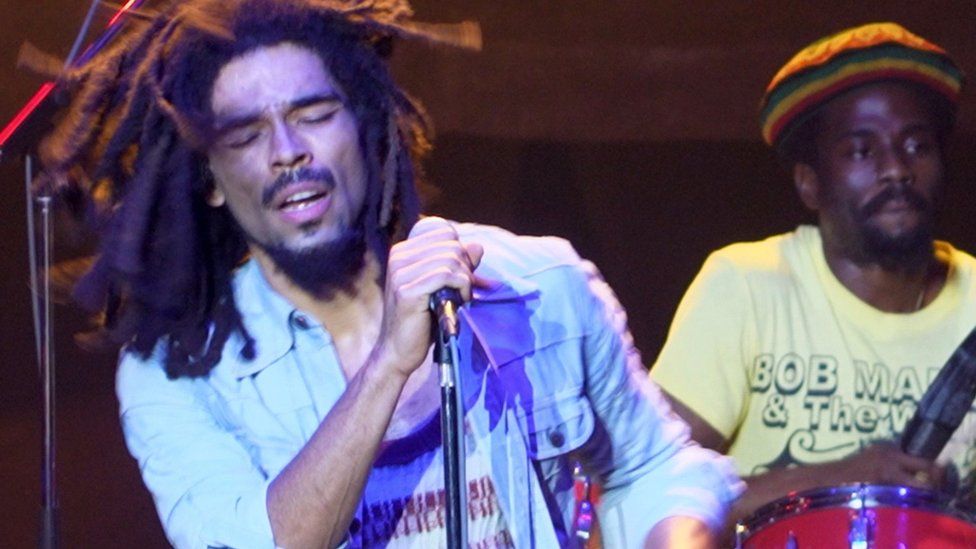

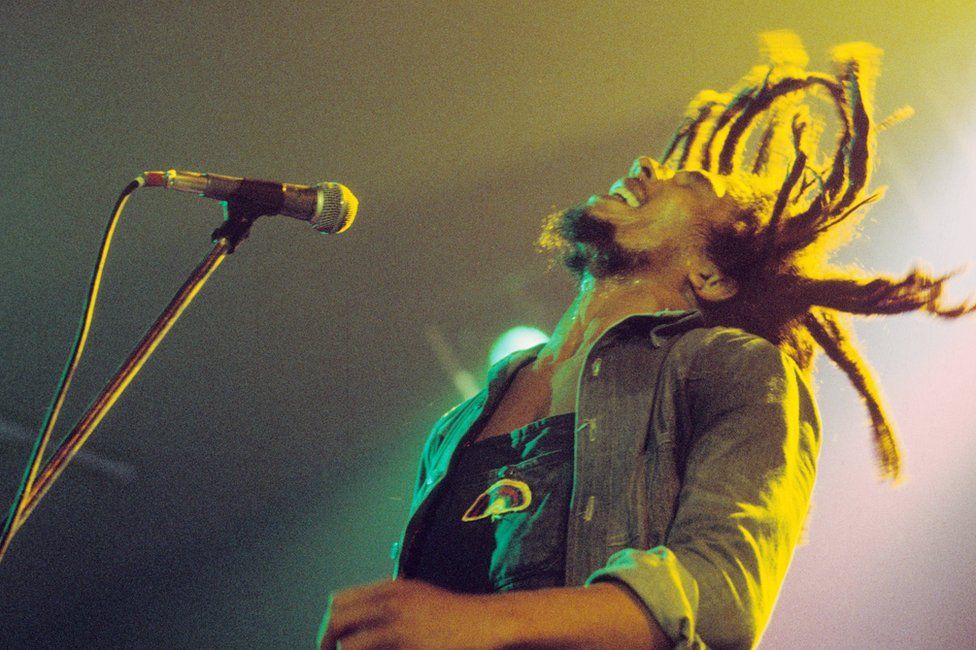

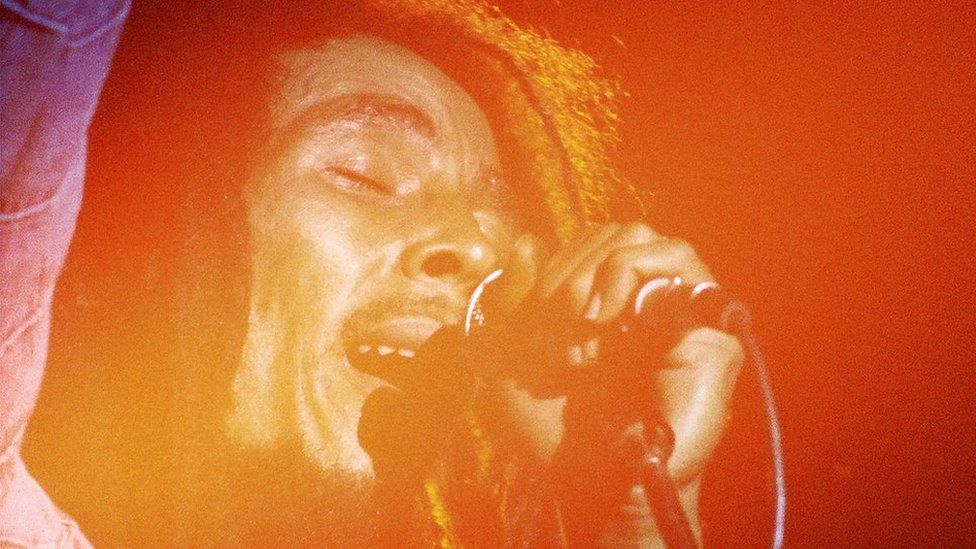

In January 2023, the BBC was invited to Alexandra Palace to watch Ben-Adir in action. The set is a faithful recreation of Bob Marley & The Wailers’ Exodus tour, filled with extras in paisley shirts, bell-bottom flares and false moustaches.

The band, which includes the sons of Wailers’ musicians Junior Marvin and Aston Barrett, play for real – jamming on Exodus and Lively Up Yourself, while Ben-Adir gets some last-minute advice from a movement coach.

Then a clapperboard claps, and the actor steps up to the mic. “Greetings in the name of his majesty,” he drawls and, suddenly, it’s like Marley is in the room.

He dances like the music has possessed him, convulsing and shaking while his dreadlocks flail.

“When he’s singing, he’s really tapping in to something else,” says the actor later. “His eyes are often closed and he’s trying to connect to the message of the song.

“It was always like he was singing for his life, every time he every time he stepped up.”

In the stalls, Ziggy Marley watches the performance with approval.

“Kingsley really did his homework,” he says. “He’s so well-prepared. I don’t think anyone else was capable of that role.”

But the film-makers are keen to stress this isn’t a sanitised, white-washed PR exercise. One Love has a loftier goal: To demystify a legend.

“Bob has become an idea for so many of us, a representation of peace,” says Ben-Adir.

“But the version of Bob the family were asking for was about what was going on for him internally. That feeling [after the shooting] of not being safe but having to front like everything’s going to be OK.”

“In those years his life was shaped a lot,” says Ziggy Marley. “And so you’re going to understand the whole of who Bob was, not just the man on stage.

“Because what you think you knew, you didn’t know.”

One Love is released in cinemas on 14 February.

Related Topics

- Jamaica

- Bob Marley

- Music

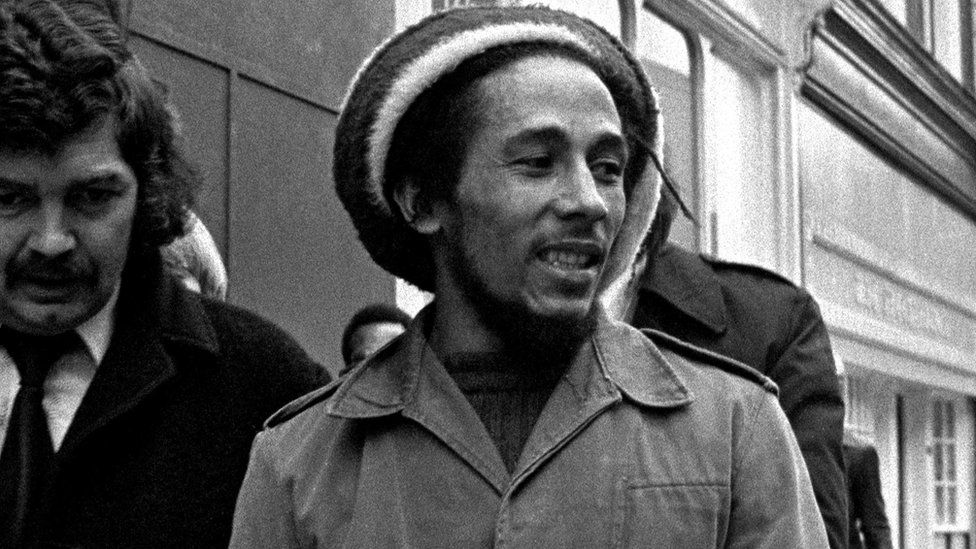

In pictures: 40 years since Bob Marley’s death

- 11 May 2021

Bob Marley house honoured with blue plaque

- 1 October 2019