“Oompa-loompa, doompity-dee, now the best director categor-ee. Oompa Loompa doompity-dong, most of these films were frankly too long.”

Fresh from starring in Wonka, Hugh Grant’s (life-size) onstage appearance at the Baftas not only saw him revive his inner Oompa Loompa when delivering the award for best director, but also openly question the length of this year’s awards season contenders.

He may have been thinking of the evening’s eventual winner, Christopher Nolan’s three-hour epic Oppenheimer, which is also expected to sweep the Oscars this weekend.

But three of the five other Bafta nominees – The Holdovers, Maestro, and Anatomy of a Fall – likewise Oscar contenders, also clock in at over two hours each.

Good thing, perhaps, that Grant didn’t have to confront Martin Scorsese’s American introspective, Killers of the Flower Moon, an Academy favourite despite its 3hr 26min runtime – the longest of this year’s best picture contenders.

But are this year’s nominated films part of a (growing) trend? If so, what does this mean for audiences, cinemas and directors?

From intermission to toilet dash

A rainy afternoon trip to the cinema may have reliably lured families, couples and single souls for decades, but film durations have fluctuated throughout this time.

The sense of screenings themselves becoming an all-day event can first be traced back to the 1960s, as directors revelled in a golden age for the silver screen.

Lawrence of Arabia ran beyond three-and-a-half hours in 1962. Cleopatra, released a year later, originally stretched to four before being cut down.

Intermissions were central to this experience as projectionists transferred over physical reels, giving audiences a natural rest break for the loo and the chance to buy ice cream.

But advancements in projector technology saw this staple of movie-going phased out by the early 80s, with 1982’s Gandhi thought to be the last major western feature to include an intermission as standard.

In the intervening decades, film lengths have steadily increased, quite literally keeping audiences in their seats.

Phil Clapp, chief executive of the UK Cinema Association, told the BBC its members are engaged in “ongoing discussions” with studios, distributors and others relevant parties about potentially reintroducing “structured intermissions”, possibly for films lasting three hours or more.

An analysis by The Economist of over 100,000 feature films released internationally since the 1930s found current popular movie runtimes to be the highest on record.

And there’s been a significant spike in recent years. Statista research across the decades reveals that, on average, the highest-grossing movies in the US and Canada have grown by around 30 minutes since 2020 alone, hitting 2hrs 23mins by 2023.

It’s not only franchise blockbusters that are responsible (yes, Indiana Jones, John Wick and Avengers: Endgame, we’re looking at you), but Oscar nominated films.

Avatar: The Way of Water, 2023’s longest best picture nominee also hit the three-hour mark.

“We’ve seen epic filmmaking do well at the Oscars in every decade,” says Karie Bible, box office analyst at Exhibitor Relations. “The very first film to win best picture in 1927 was an aviation epic called Wings that ran for two hours and 24 minutes.”

“Epic films often mean epic storytelling,” she explains. “These films are larger than life and often encompass a long, developed story that ask people to be emotionally invested.”

But this artistic rationale is being pushed to its limits – with audience bladders left bursting as directors are empowered like never before.

Streaming ‘Cold War’

The Cold War between streaming and cinema over the past decade has made the name behind the camera almost as coveted as any A-list actor.

As streaming services vie with Hollywood for credibility and prestige they’ve thrown huge amounts of money at directing talent – often far outmatching anything a legacy studio can offer – with success.

Before Scorsese partnered with Apple for Killers of the Flower Moon, he turned to Netflix to fund his Oscar nominated three-and-a-half-hour mob movie The Irishman, telling the BBC he “couldn’t get financing” from Hollywood to match his ambition.

This video can not be played

To play this video you need to enable JavaScript in your browser.

The template has similarly tempted David Fincher, Rian Johnson and latterly Ridley Scott – who has hinted at releasing a four-hour cut of Napoleon on Apple TV, despite his original version already being nearly three hours.

The dynamic can weaken producer control and inflate runtimes. In his podcast review for Killers of the Flower Moon, Mark Kermode explained: “We hear stories about… people making films for studios for theatrical exhibition, then you end up having fights with the producers about [length]. If you’re a streaming service, they don’t care.”

This challenge comes at a hefty price for traditional film studios, at a time when tinseltown is having to find a delicate balance between squeezed costs – exacerbated by the pandemic – last year’s strikes and the challenge of tempting people away from lockdown-inspired home streaming.

“Casual moviegoing, where you wait until the weekend to pick what to see, has pretty much been supplanted by streaming,” Erin Brockovich producer Michael Shamberg told Vanity Fair’s Natalie Jarvey for her aptly named article: Why Are Movies Sooooo Long?

“Now when you leave your house to pay to see a movie, you want an emotional sure thing for your time and effort. You also want a bigger experience than streaming a movie in your living room,” he added.

The knock-on effect of “event” cinema, increasingly tied to social media buzz, sees the industry – and cinemas themselves – reliant on goldrush titles, be it Top Gun: Maverick post-lockdown or Oppenheimer last year, to mask over the cracks of reduced pulling power.

And even taking Nolan’s popularity as a director into account, the mainstream success of Oppenheimer, on paper, a three-hour historical biopic, benefitted hugely from the Barbenheimer phenomenon: an accidental marketing dream.

- Barbenheimer was wonderful for cinema, Murphy says

- Immersive screenings can weaken films – Scorsese

Outside that near one-off event, the overwhelming temptation to “go long” seems to be partially wearing thin, with cinemas, audiences and directors.

Cinema chains, says Clapp, can struggle with a flurry of longer films, as this “means less screenings”, choice and ultimately tickets sold – only a fraction of which can be made up by popcorn and fizzy drinks, or luxury seating.

“We would never want to dictate creative licence, but there’s a desire amongst a proportion of the audience for a break,” he says, pointing to the potential for intermissions, and their confectionary window.

Cinema chain Vue was among a handful worldwide to forgo distribution agreements and trial intervals during Killers of the Flower Moon.

“Analysis showed customers would like to see the return of intermissions,” Vue’s chief executive, Tim Richards, told The Guardian last October. “We’ve seen 74% positive feedback from those who have tried our interval.”

Clapp describes it as a “live debate” especially with intermissions remaining in other global markets.

“The concern is that wherever you drop the curtain, so to speak, you’ll kill the narrative structure, but this doesn’t need to be the case with careful planning – arguably people getting up midway through a film causes more disruption,” he says.

Scorsese, for his part, urged viewers to show “commitment” to cinema, lambasting complaints in light of TV binge-watching at home.

“You can sit in front of the TV and watch something for five hours… there are many people who watch theatre for 3.5 hours … give cinema some respect,” he told Hindustan Times.

But not every director agrees. As Holdovers’ mastermind Alexander Payne bemoaned: “There are too many damn long movies these days.” Lengthy runtimes, he added, should always be “the shortest possible version”.

For Nolan, the relationship with the audience remains foremost in his mind: “I view myself as the audience. I make the films that I would really… want to watch,” he told BBC Culture editor Katie Razzall.

For younger audiences however, frequently cast as rejecting long-form viewing in the age of TikTok and YouTube shorts, Nolan’s epics – often near three hours – should not appeal.

But Dune director Denis Villeneuve says Oppenheimer’s success proves the opposite. He argues younger audiences value watching and paying for longer films, provided they offer “something substantial”. “They are craving meaningful content,” he told The Times.

Dune: Part Two, released last week, outlasts the original film’s 155-minute runtime by ten minutes, providing five hours of desert adventure in total.

One nationwide chain, Showcase Cinemas, offered both instalments back-to-back across the opening night.

Hopefully there was an intermission.

Related Topics

- Streaming

- Bafta Awards

- The Oscars

- British cinema

- Film

- Cinemas

17 facts you need to know about this year’s Oscars

- 18 hours ago

Barbie misses key Oscar nods for Gerwig and Robbie

- 23 January

Barbenheimer was wonderful for cinema, Murphy says

- 7 February

Lily Gladstone: The actress who could make Oscars history

- 30 January

Can anything stop Oppenheimer’s march to the Oscars?

- 14 January

10 things we spotted in the Oscars class photo

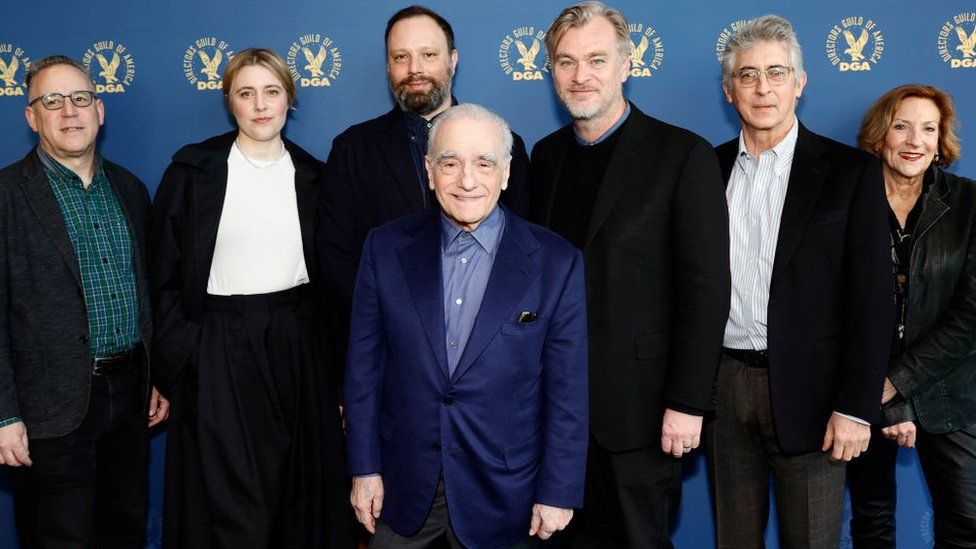

- 13 February