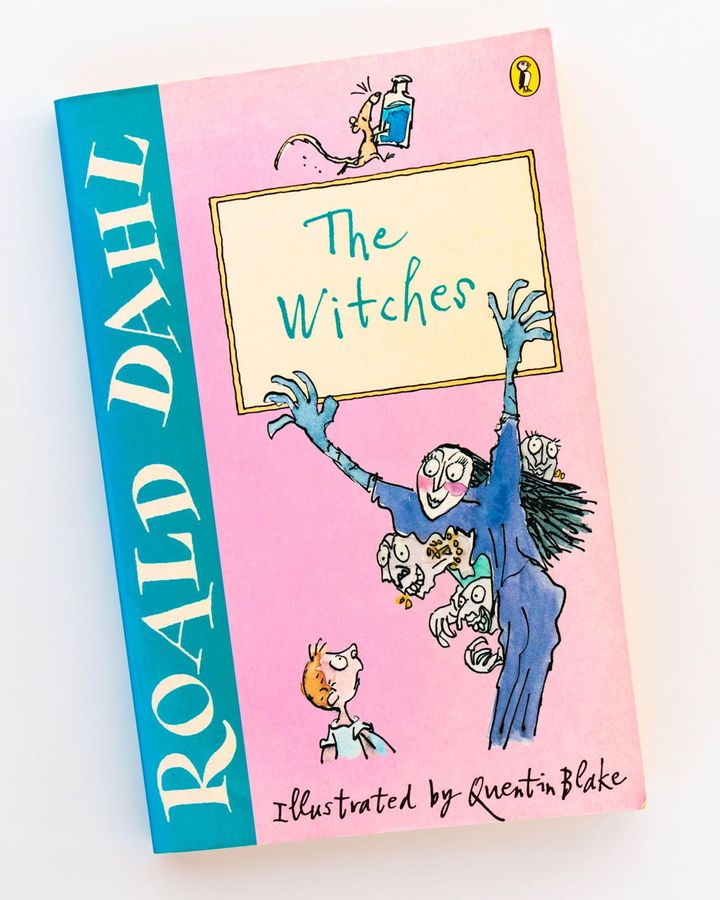

Sir Salman Rushdie had his say. The UK Prime Minister Rishi Sunak weighed in. The New York Times published a piece debating the pros and cons. Steven Spielberg offered his opinion. Even the Queen seemed to refer to it. When The Telegraph revealed earlier this year that hundreds of changes had been made to the original text of Roald Dahl’s children’s novels in their latest editions, the news caused quite a stir. The newspaper found that Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, The Witches, Matilda and more than a dozen other titles had words relating to weight, height, mental health, gender and skin colour removed. Some of the changes seemed baffling.

Read more about BBC Culture‘s 100 greatest children‘s books:

– The 100 greatest children’s books

– Why Where the Wild Things Are is the greatest children’s book

– The 21st Century’s greatest children’s books

– Who voted?

For example, “You’ve gone white as a sheet!” in The BFG was now “You’ve gone still as a statue!” and nor could the BFG wear a “black” cloak. James and the Giant Peach’s “Cloud-Men” had become “Cloud-People”. “Aunt Sponge, the fat one, tripped over a box” in the same novel was now “Aunt Sponge tripped over a box”. In fact, the word “fat” had been excised from every book. And lines not written by Dahl had been inserted. In The Witches, a reference to the fact that witches are bald and wear wigs was now followed by the new line: “There are plenty of other reasons why women might wear wigs and there is certainly nothing wrong with that.” Rushdie described the changes

The Telegraph newspaper found that several of Roald Dahl’s titles, including The Witches, had words removed (Credit: Alamy)

In the New York Times, Suzanne Nossel, the chief executive of the free speech charity, PEN America, was quoted as saying: “You want to think about the precedent that you’re setting, and what would happen if someone of a different predisposition or ideology were to pick up the pen and start crossing things out.” Asked about the changes, Spielberg responded: “For me, it is sacrosanct. It’s our history, it’s our cultural heritage. I do not believe in censorship in that way.” And during a reception for authors at Clarence House, even Queen Camilla appeared to criticise the changes. “Please remain true to your calling, unimpeded by those who may wish to curb the freedom of your expression or impose limits on your imagination,” she said.

Although Dahl’s reputation is not what it once was – his family apologised after his death for his anti-Semitic remarks – the broad consensus seemed to be that this was the first step on the path to a literary wasteland of bland, boring identikit texts. Revisions such as these, some maintained, were inimical to the idea that literature might challenge or provoke. If every text were stripped of every single thing that someone might conceivably be offended by, there wouldn’t be much left. After all, even Maurice Sendak’s Where the Wild Things Are, ranked number one on BBC Culture’s recent children’s book poll, met with some opposition on publication on the grounds that sensitive children might find it frightening.

Although Dahl’s reputation is not what it once was, many – including the UK’s prime minister – opposed the changes to his books (Credit: Getty Images)

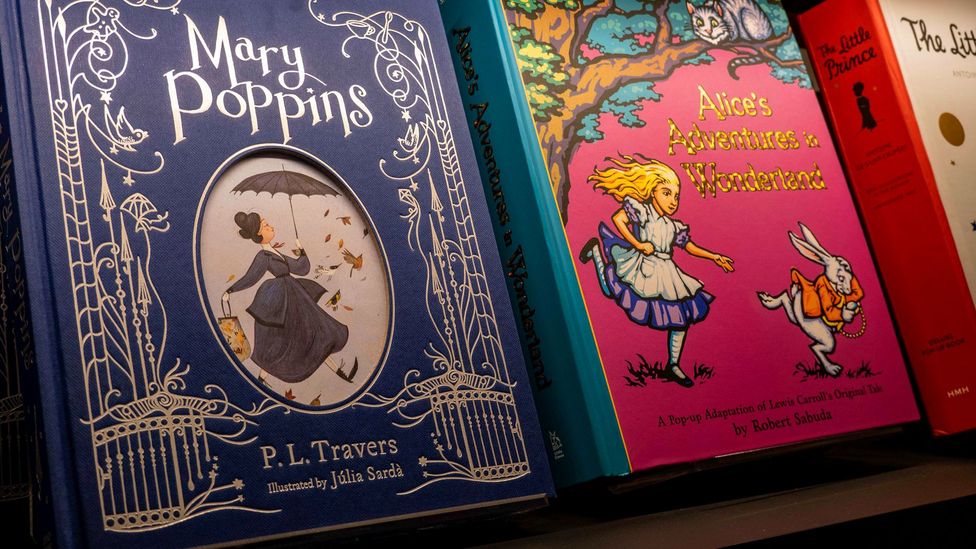

However, the journalist and author Sam Leith, who is currently writing The Haunted Wood, a history of children’s literature, points out that the revision of texts of children’s books is nothing new. Hugh Lofting’s 1920 book The Story of Dr Dolittle was rewritten to remove a subplot in which a black character wishes to be turned white. PL Travers’ 1934 novel Mary Poppins (51 on BBC Culture’s list) was revised twice by the author to remove ethnic stereotypes. In the late 1960s, Dahl himself agreed to “de-Negro” (his words) the Oompa-Loompas in his 1964 book Charlie and the Chocolate Factory (18 on the list).

“The culture war position that ‘it’s woke Stasi stuff’ was sort of nonsense because children’s stories are quite robust,” Leith tells BBC Culture. “It’s not like the government or some sinister organisation is removing Roald Dahl’s original texts from libraries. Any scholars who want to understand what the original text said can go and look in the archives. I think the problem with the Dahl changes, to me, was that they made a complete mess of it. It’s not that the texts are sacred or that removing a single word would utterly destroy the literary quality of the story but that they’d just done it really, really badly. The problem is, at the moment, Young Adult and children’s literature is absolutely at the heart of the whole cancel culture row.”

‘Harmful stereotypes’

Certainly writers do seem to be cautious about putting their head above the parapet. BBC Culture contacted five prominent children’s authors to ask if they wished to comment on this issue. Four did not want to contribute, one did not respond. Amanda Craig is a novelist as well as a critic of, and advocate for, children’s books. “Children’s authors are very, very cowed and very anxious not to upset readers,” she tells BBC Culture. “I think they have been absolutely terrified of offending anybody for a long time.

“Regarding a historic text, the author of which is dead, even if it is offensive, and a number of children’s books are offensive, I think we still have to let it stand because otherwise you are lying about the past and I’m against censorship of the past.”

The Bookseller is the magazine for the UK publishing industry. Caroline Carpenter, the Bookseller’s children’s editor and deputy features editor, tells BBC Culture: “Most of the controversy around this issue seems to be centred on classic texts, which are still widely read and obviously very nostalgic for many people. Plus, this throws up difficult questions around what are or aren’t appropriate changes to make when an author is dead and cannot agree to them. For example, I’m not sure if there was the same backlash regarding the David Walliams edits” (HarperCollins removed a story from Walliams’s The World’s Worst Children after it was criticised for using “harmful stereotypes” in its depiction of a Chinese boy). “I think that what is more common with contemporary children’s books is that now this sort of editing is being done before they are published, sometimes with the help of sensitivity readers – which can be controversial too. It’s a slightly different issue, but covers some of the same ground.”

PL Travers’ classic 1934 novel Mary Poppins was revised twice by the author to remove ethnic stereotypes (Credit: Alamy)

Puffin, the UK publisher of Dahl, worked with sensitivity readers from a consultancy called Inclusive Minds to make the changes. The Bookseller has described “sensitivity readers” as “readers from specific backgrounds, or those with particular life experiences reading manuscripts to help eliminate problematic and harmful representations”. If, for example, an author is depicting a character of a religion or from a culture other than the writer’s, they might use a sensitivity reader to check for faux pas. Their use originated in the US where sensitivity reading is thought to be more widespread than in the UK.

‘An outcry’

However, in America there was an outcry over the Dahl edits, with the author’s US publisher announcing that there are no plans for similar revisions in the US editions. Emma Kantor is deputy children’s book editor at Publishers Weekly, the US book industry’s trade magazine. She says such edits there are usually less extensive. “My sense is that the revisions are typically minor ones, done for clarity. One example of a backlist title that has undergone this kind of ‘low-key’ revision is Judy Blume’s Are You There God? It’s Me, MargaretThe original 1970 edition featured references to sanitary napkins with belts, which are no longer in use. Starting in the late ’90s, subsequent editions were updated with references to self-adhesive pads, to avoid confusing contemporary young readers. Some fans who grew up reading the book expressed disappointment that the retro feel was lost with this change, but otherwise, there wasn’t much upset.”

The debate will no doubt continue as will, in all likelihood, the practice of revising classic books although after the fierce debate over the Dahl changes, Puffin announced that the works would also be reissued in their uncensored form so readers could choose which version they preferred. Kantor suggests one alternative way forward. “Reissues of backlist titles also sometimes have added introductions, as an alternative to revisions,” she says. “I think introductions are a great (and minimally invasive) tool for adding context to older texts – not necessarily for young readers, but for the teachers, librarians, parents and guardians who are putting books into kids’ hands or reading aloud with them. In addition to providing a deeper understanding of the book and the time in which it was written, these kinds of intros can open up valuable discussions without changing the author’s words.”

It is perhaps worth remembering that it is not just children’s literature that is subject to these sorts of revisions. Both Agatha Christie and Ian Fleming have recently had offensive references removed. Nor is it a new practice. Charles Dickens was so stung by the hurt reproaches of a Jewish reader over his depiction of the villainous Fagin that he halted a reprinting of Oliver Twist mid-run and removed many of the references to Fagin as “the Jew”. The kindly Jewish character of Mr Riah in Our Mutual Friend, Dickens’s last completed novel, seems to have been intended as an atonement.

And, of course, the very word “bowdlerisation”, bandied around so much recently, originated with over-zealous 19th Century sensitivity reader Thomas Bowdler rewriting Shakespeare to remove, among other things, sexual innuendo. If the Bard can be rewritten, so can anyone.

Read more about BBC Culture‘s 100 greatest children‘s books:

– The 100 greatest children’s books

– Why Where the Wild Things Are is the greatest children’s book

– The 21st Century’s greatest children’s books

– Who voted?