Alice Neel was never one to bow to convention, neither in the way she lived her life nor in the manner in which she chose to paint. Born at the turn of the 20th Century, she grew up in a Pennsylvania town devoid of culture in a society riven with racism, homophobia and misogyny. Yet she escaped to study art and went on to create astonishingly innovative portraits of those generally ignored by society – her Puerto Rican neighbours in Spanish Harlem, black intellectuals, communist activists, pregnant women and sex workers. “I am a collector of souls… I paint my time using the people as evidence,” said Neel.

More like this:

– Unflinching images that confront injustice

– The 80s artists who predicted today

– The portraits that question history

Neel insisted on painting figuratively at a time when Abstract Expressionism was dominating the art world, a decision that meant she went largely ignored until late in her career. But Neel refused to compromise. “She understood it as a political decision… she saw abstraction as a kind of move away from humanity and human plight,” says Eleanor Nairne, curator of Alice Neel: Hot Off the Griddle

“A common thread with the people who she paints is that she admires them, and she often admires them because they share her political sensibilities. She is someone who really lived life her own way and suffered terribly in certain moments in her life and I think she was interested in people who were sympathetic to suffering and who had real courage,” says Nairne.

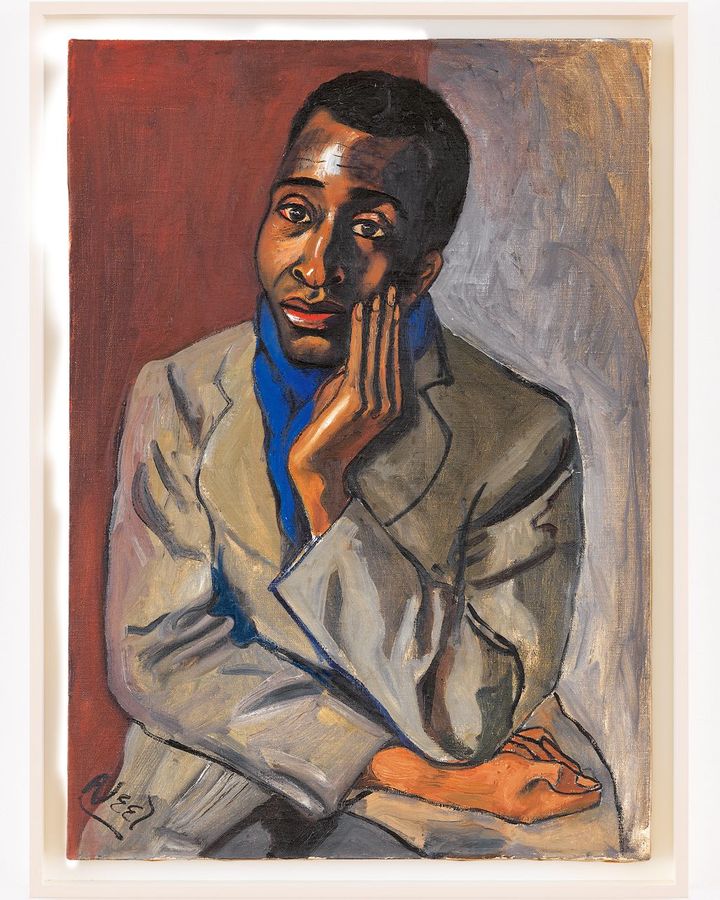

Many of Neel’s portraits were of artists and intellectuals, like Harold Cruse, who shared her passion for civil rights and creativity (Credit: The Estate of Alice Neel)

That suffering included the death of one daughter to diphtheria and the virtual kidnapping of another by her husband, the artist Carlos Enríquez Gómez, who took her to Havana, making false promises to Neel that he would send money for her to join them. The trauma saw Neel admitted to hospital with depression at the end of 1930 and the following year she was placed on a suicide ward. A social worker encouraged her to draw and she began sketching the patients around her, later remarking that: “It was the drawing that helped me decide to get well.”

Following her recovery, Neel moved to Greenwich Village with her new lover, Kenneth Doolittle, who introduced her to members of the Communist Party. The pair would regularly attend demonstrations while also immersing themselves in the vibrant artistic community around them. It was at this point Neel painted her notorious nude portrait of a local eccentric, Joe Gould, featuring no fewer than five penises, a work that reveals the mischievous, joyous side to her personality that remained undiminished despite the hardships she and those around her faced.

‘Dignity and nobility’

In 1933, at the height of the Great Depression, she was invited to join the Public Works of Art Project. Part of Roosevelt’s New Deal, the programme was designed to give unemployed artists a small salary in exchange for making artworks to decorate public buildings. “I think living through that moment would have been enormously powerful for her political sensibility. She’s living through a period where artists are literally on the breadline. People are starving. She goes to the investigation of poverty at the Russell Sage Foundation and one of the women being interviewed is said to have been living underneath her car with seven children. The kinds of poverty being witnessed at that time are unfathomable,” says Nairne.

During the 1930s, Neel would paint street scenes that illustrated the extreme poverty endured by so many, as well as depictions of demonstrations and striking workers. Neel herself understood what it was like to have little money. After the WPA was disbanded, she relied on welfare payments until the mid-1950s. She also fiercely believed that a lack of money, recognition or acceptance by society at large did not diminish a person’s worth. Dignity and nobility are words that are often used when describing Neel’s treatment of her subjects. “The dignity and the nobility are about the encounters. There are two people each recognising the other’s merit,” says Nairne.

She points to Neel’s portraits of Georgie Arce, a Spanish boy who she first met when he was about 10 or 11 and playing truant. In one particularly poignant and powerful image he can be seen holding a knife while staring at the viewer. Yet rather than seeming threatening, the boy appears vulnerable and pained. “She’s very sensitive to the fact that she’s living in Spanish Harlem, one of her own sons has a Puerto Rican father, and that Latin American culture is not being properly recognised or taught in elementary schools in those areas. She’s very empathetic and conscious of what his situation might have been,” says Nairne. “There’s this story that when she was away he’d just lie on the threshold of her apartment waiting for her to come back. Her apartment was clearly a space that felt safe for him.”

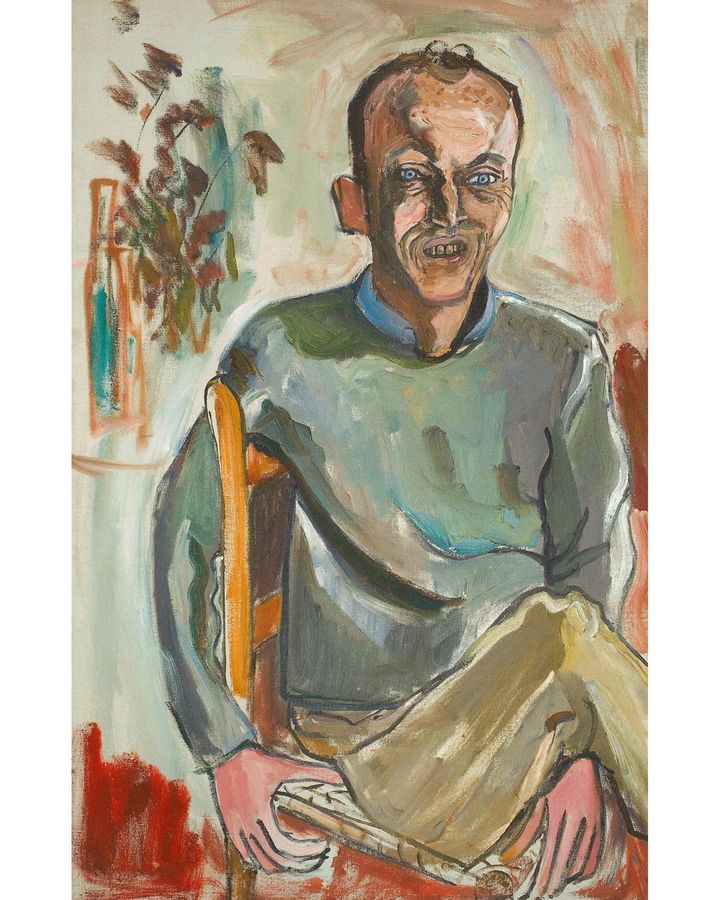

Neel painted Frank O’Hara, a notable poet and critic, in 1960, after a therapist encouraged her to get her work before the world (Credit: The Estate of Alice Neel)

Neel’s apartment seems to have been an environment where many people felt safe. It’s the setting for a large number of her psychologically penetrating portraits, many of them featuring artists and intellectuals who shared her combined passion for civil rights and creativity. Scholar Harold Cruse (1950) sits with one hand on his cheek, the other held in a fist on his lap, thoughtful yet nervy. Rita and Hubert (1954) reveals the relaxed intimacy between the writer Hubert Satterfield and his partner Rita, at ease in their own company and that of Neel, who they knew would not frown on their mixed-race relationship when the vast majority at the time would.

“She said that if she hadn’t have been a painter she would have been a psychoanalyst, because she plumbs the depths of the human psyche. When she’s talking to these people as they sit for her, she’s trying to create an environment in which they can make themselves available to her,” says Nairne. Neel herself underwent therapy in the late 1950s after the death of her mother sent her spiralling into depression. The experience would have a pronounced effect on her career trajectory. “There’s often a side A and a side B of an artist’s career, life changes that cause a dramatic shift in the work they are making, and I think for Alice Neel, the shift really happens when she starts to see a therapist for the first time,” says Nairne.

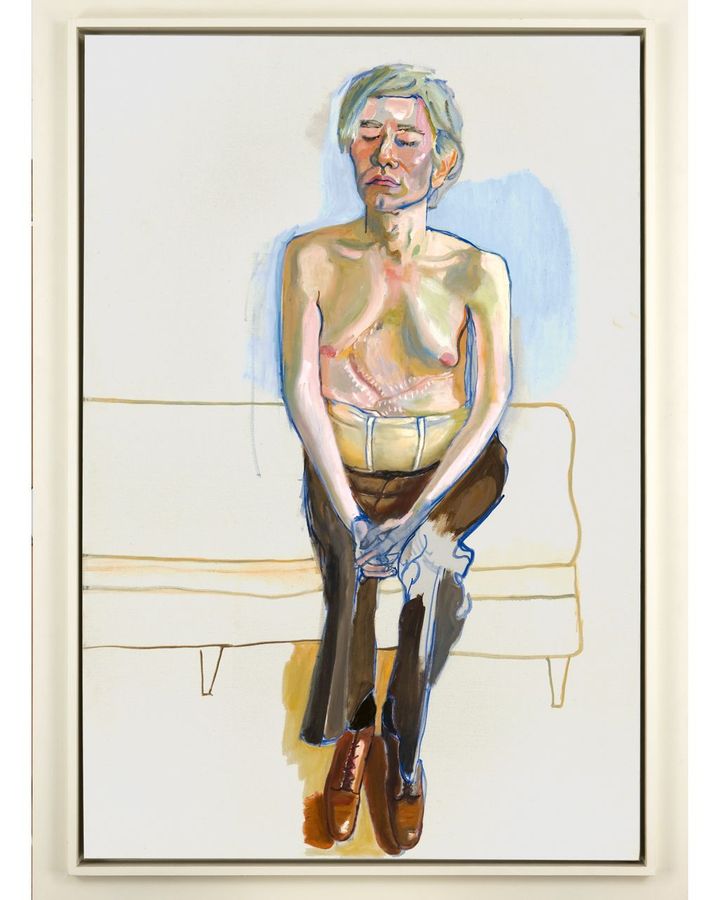

Neel painted a number of celebrated figures, like Andy Warhol, in a picture that revealed his scars and surgical corset after he was shot (Credit: The Estate of Alice Neel)

“One of the things he does is encourage her to get her work before the world. If she wants to paint a more celebrated figure like Frank O’Hara, then she should go right ahead and approach him.” Neel painted O’Hara, a notable writer and critic, in 1960, and would go on to paint a number of celebrated figures including Andy Warhol. The painting in which he sits bare chested revealing the scars and surgical corset he was obliged to wear after being shot by Valerie Solanas is astonishingly intimate. “What’s so wonderful about the Warhol portrait in particular is that it’s not like any image of him we have seen anywhere else. That Warhol allows her to paint him like that is an enormous act of trust,” says Nairne.

‘A life force’

The 1960s and 70s saw Neel finally begin to get the recognition she deserved with laudatory commentary in the press and a major retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art in 1974. One of the last people Neel painted was the artist, filmmaker and former sex worker Annie Sprinkle. Neel, then in her 80s, painted Sprinkle in full fetish gear, bare breasted with her pierced labia revealed though crotchless underwear. What could have been a titillating image is in Neel’s hands full of warmth and humanity. Sprinkle was introduced to Neel by Dennis Florio, a picture framer to the art stars, who Neel had painted in a dapper red velvet suit looking like Marcel Proust. “We’d go over and Nancy, her daughter-in-law, would make tea and we’d bring muffins and sit around and look at her paintings,” Sprinkle tells BBC Culture. “We did that two or three times and then she wanted to paint me, so I brought a suitcase full of clothes and props. She picked that leather outfit. I’d just had my labia pierced, and I’d shown that to her and she was delighted. She was always full of joy and wonder,” remembers Sprinkle.

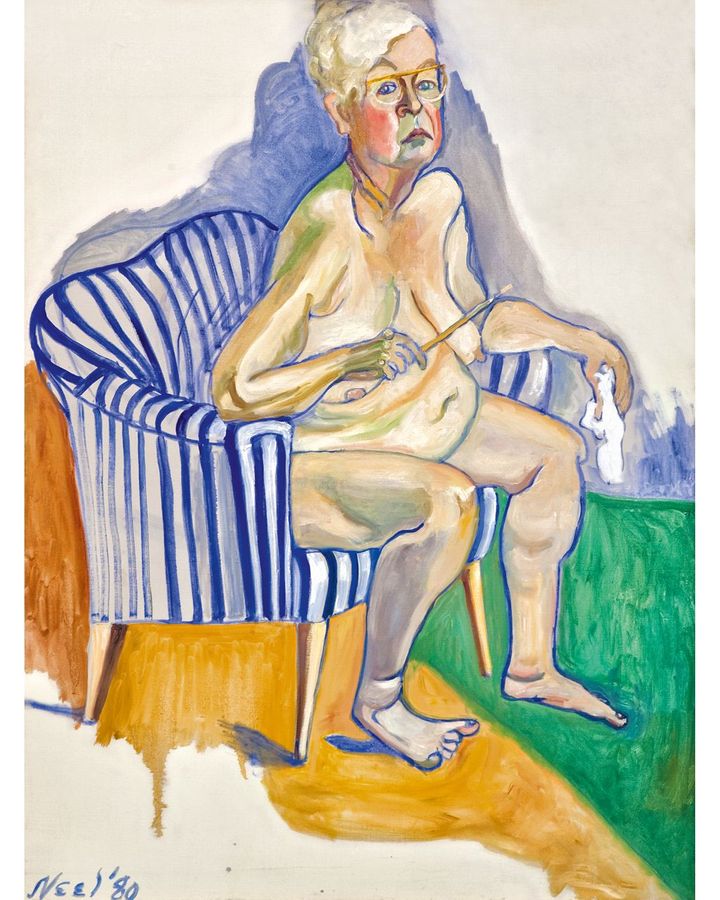

Neel’s nude self-portrait – painted when she was 80 – opens the Barbican exhibition (Credit: The Estate of Alice Neel)

The painting took around three sittings to complete and Neel being Neel, there was much conversation. “She was very interested in what I was doing, which was bridging art and porn,” says Sprinkle. “I was of course thrilled that this 80-something woman was fearlessly painting me, joyfully painting me, because in ’82 we were a small fringe group, and very much prejudiced against,” Sprinkle tells BBC Culture. “I think she really captured me in a non-judgmental and beautiful way, but also with depth and complexity.”

Sprinkle’s portrait closes the show. Opening it is Neel’s glorious nude self-portrait, completed when she was 80. “All my life I wanted to do a nude self-portrait, but I put it off till now – when people would accuse me of insanity rather than vanity,” she quipped.

In between are portraits that thrum with life, vitality and Neel’s particular insight, born of her own journey to the edge. “I think many of the most interesting artists have had some extreme life experiences that allow them to paint very expansively because they paint from a place in which they have experienced altered states of mind and body and that can make for a very rich art practice,” says Nairne.

“To have that kind of nerviness to your work can be connected to a capacity to give a painting the feel of life force. You need a kind of extra bodily sensitivity and I think she was somebody who had that.”