For fans of disco and baseball alike, the night of 12 July 1979 is one to remember for all the wrong reasons. In a notorious promotional stunt, a Chicago DJ named Steve Dahl detonated a dumpster filled with disco records between White Sox games at Comiskey Park, leading to a riot. Years later, Dahl claimed that disco was “probably on its way out” but admitted that his stunt “hastened its demise”. Nile Rodgers of the disco group Chic told biographer Daryl Easlea, “It felt to us like a Nazi book-burning.”

More like this:

– Why disco should be taken seriously

– Stunning music from the US’s most notorious prison

– The forgotten godfathers of hip-hop

The so-called Disco Demolition Night figures in every history of disco but The Saint of Second Chances, a new Netflix documentary about flamboyant White Sox owner Bill Veeck and his son Mike, approaches it as a baseball story. Indeed, at the time it was seen as a shameful night for major league baseball rather than the symbolic death of disco. The Chicago Tribune damned it as “an outrageous example of irresponsible hucksterism that disgraced the sport of baseball” in a leader column headlined Veeck asked for it.

In the summer of 1979, the flailing White Sox were attracting on average just 15,000 fans to a stadium with a capacity of almost 45,000. Bill Veeck needed a gimmick to boost ticket sales, and Mike, the team’s director of marketing, turned to Steve Dahl. The previous Christmas, Dahl had been dropped from Chicago radio station WDAI when it switched, like so many others, from rock to disco. He reinvented himself at rival station WLUP as an anti-disco culture warrior who encouraged his followers, the Insane Coho Lips, to besiege and occupy disco nights in the city with the rallying cry “Disco sucks!”

DJ Steve Dahl had positioned himself as an anti-disco culture warrior, encouraging his followers to occupy disco nights in the city (Credit: Getty Images)

Comiskey Park had previously hosted a “Salute to Disco”, with dancers on the field. Mike figured, “We ought to have a night for people who disco.” He had the brainwave of offering discounted 98 cent tickets to anyone who brought along a disco record for Dahl and his sidekick Garry Meier to ceremonially detonate between games during the White Sox doubleheader against the Detroit Tigers. On the night, the stadium was filled to capacity, with thousands more people fighting to get in. The dumpster designated for the disco vinyl soon overflowed, so many of the excess records were repurposed as aerial missiles. The first game unfolded to a ceaseless chant of “Disco sucks!” Afterwards, Dahl and Meier circled the field in a jeep, wearing military fatigues. “This is now officially the world’s largest anti-disco rally!” Dahl bragged.

Once Dahl had exploded the vinyl records, thousands of spectators stormed the field (Credit: Getty Images)

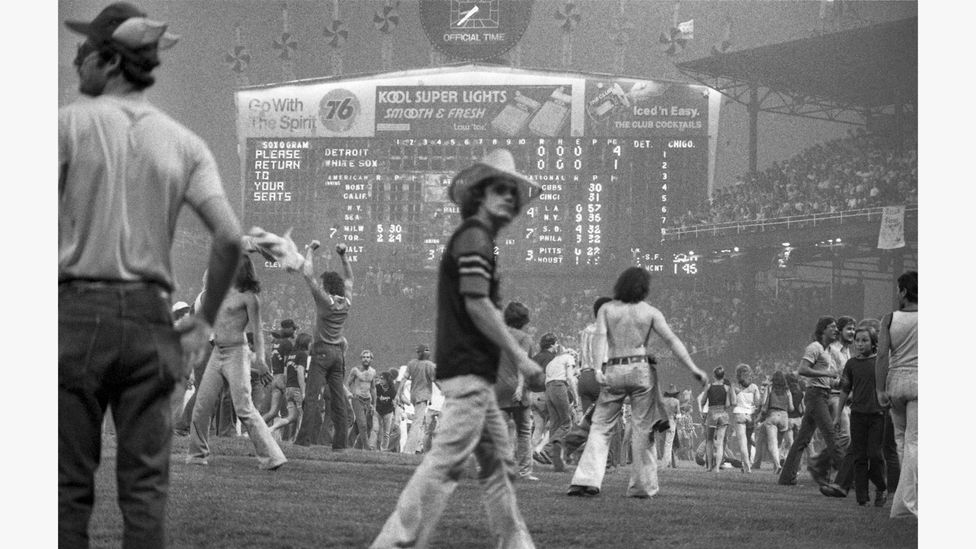

Dahl triggered the explosives, sending shards of shattered vinyl 200ft into the air. More than 5,000 fans took this as their cue to storm the field, tearing up the grass, kindling bonfires, and stealing the bases, until they were dispersed by riot police. With the ground a battlefield, the White Sox had to forfeit the second game. This mayhem was all televised, making it an international scandal. The Veecks were disgraced. Bill sold the team the following year. “That event was so traumatic it broke his heart,” author Neal Karlen says in the documentary. Mike became persona non grata in the world of baseball. Jimmy Piersall, the White Sox’s own broadcaster, called Disco Demolition Night “the worst promotion in the history of the world”.

Disco’s last gasp

From a music perspective, Dave Marsh of Rolling Stone saw the debacle as an ugly expression of the reactionary backlash that was sweeping American in 1979, the year the Reverend Jerry Falwell founded the Moral Majority, a conservative evangelical lobbying group. “White males, eighteen to thirty-four are the most likely to see disco as the product of homosexuals, blacks, and Latins,” Marsh wrote, “and therefore they’re the most likely to respond to appeals to wipe out such threats to their security.”

Dahl has always denied bigotry. “This event was just a moment in time. Not racist, not anti-gay. Just kids, pissing on a musical genre,” he insisted in his 2016 memoir Disco Demolition: The Night Disco Died. Yet at the time he derided disco as effeminate and described rock’n’roll as “threatened as a species”. A media consultant canvassing young men on behalf of radio stations in 1979 reported, “Obviously, some people dislike disco for being black and gay.” Ushers at Comiskey Park noticed that fans weren’t just bringing along disco records. They were more likely to deposit funk and R&B discs than, say, Debby Boone’s gloopy 1978 chart-topper You Light Up My Life. In their eyes, the target wasn’t mainstream pop music but black music.

The entire incident was televised – and it became an international scandal (Credit: Getty Images)

Disco didn’t perish overnight. Donna Summer’s Bad Girls led an all-disco top three in the Billboard Hot 100 that week, remained at number one for five weeks and was succeeded by Chic’s Good Times. But that was the last gasp of disco’s chart supremacy after two years during which it accounted for three in four chart-toppers. Across the land, radio stations who had not long ago switched from rock to disco hastily U-turned, while thousands of discotheques closed their doors.

In the long run, though, disco won. In Whit Stillman’s 1998 movie The Last Days of Disco, one character delivers a passionate defence of a misunderstood scene: “Disco was too great, and too much fun, to be gone forever! It’s got to come back someday.” That same year, a Chic sample powered Stardust’s massive hit Music Sounds Better With You, initiating a craze for disco-house records which was then picked up by Madonna and Kylie Minogue. Music critics began celebrating disco’s underground roots and its pioneering gay, black and Hispanic DJs. By the time Nile Rodgers appeared on Daft Punk’s Get Lucky in 2013, the rehabilitation was complete. In 2019, the White Sox’s decision to invite Steve Dahl to Comiskey Park to commemorate the 40th anniversary of Disco Demolition Night was widely condemned. “I wouldn’t have done it [in 1979] if I thought it would hurt anyone,” Mike Veeck says in the documentary.

‘Destined to collapse’

Such revisionism is all to the good but it risks simplifying the nature of the disco backlash. Disco evolved in New York in the early 1970s, when DJs such as David Mancuso and Nicky Siano revolutionised dancefloors with ingenious blends of long, percussive soul and funk records. Rolling Stone magazine first covered the scene in 1973. Billboard launched its American Disco chart in November 1974. Within months Billboard was claiming that disco was “rapidly becoming the universal pop music”. When any cultural force becomes that big, that quickly, it inspires opposition. “Everybody hates it,” wrote the critic and future Mercury Music Prize founder Simon Frith in 1978. “Hippies hate it, progressives hate it, punks hate it, teds hate it, NME hates it… Disco is the sound of consumption.”

Chic’s Good Times topped the Billboard 100 later in 1979 – but it was the last gasp for disco’s supremacy over the charts (Credit: Getty Images)

Nor were disco’s discontents entirely white: the civil rights activist Jesse Jackson accused it of smothering the social consciousness of 1970s soul, while Funkadelic’s George Clinton deemed it insufficiently funky. Even some of the hipsters who had spearheaded disco thought that by 1979 the genre had become suffocatingly mainstream and deeply uncool. As opportunists jumped on a winning formula, not every disco record was as thoughtful and deft as Chic’s output.

Nile Rodgers could see the backlash gathering in April when he told Rolling Stone, “Disco is the new black sheep of the family, so everyone has to jump on it”. Two days before Disco Demolition Night, the New York Times published a column called Discophobia, in which Robert Vare equated disco with national decline: “The Disco Decade is one of glitter and gloss, without substance, subtlety or more than surface sexuality… After the lofty expectations, passions and disappointments of the 1960s, we have the passive resignation and glitzy paroxysms of the Disco 1970s.”

Even in a world without “Disco Sucks”, then, pop music would have been ready to move on. In his book Major Labels, the critic Kelefa Sanneh argues that the disco crash made way for new forms of blockbuster dance-pop such as Michael Jackson’s Thriller and Madonna’s Like a Virgin (produced by a rejuvenated Nile Rodgers), not to mention the rise of hip-hop and the birth of house music. (In a pleasing twist, the first ever house record, On and On by Jesse Saunders, was co-written by Vince Lawrence, who had been an usher at Comiskey Park on 13 July 1979.) Far from dying, dance music became more innovative and diverse. Modern club culture is indebted to the rise of disco but also to its fall.

This is not to deny the toxic currents of racism, misogyny and homophobia that erupted at Comiskey Park. Dahl and his Coho army certainly wanted to kill disco, but they should not be credited with doing so. As a ubiquitous consumer phenomenon, disco was destined to collapse. As a form of music, and a fine way to spend a Saturday night, it lives on.