This November, it will be 60 years since the assassination of President John F Kennedy. A significant anniversary usually provides a chance to remember and reflect on past events – but, in the case of JFK’s death, interest has never really faltered. Almost immediately after those gunshots rang out on a sunny autumn day in Dallas, speculation over Kennedy’s death began, and it hasn’t stopped since.

More like this:

– The greatest spy novel ever written

– The hit song that has divided the US

– A watershed moment for ‘faith-based’ filmmaking

Thousands of books, documentaries, podcasts, TV shows and Hollywood movies have been dedicated to the events of 22 November 1963, and the shockwaves it sent around the world. And yet, the more information that emerges, the more the doubt over what really happened grows. No other event has spawned as many conspiracy theories – from the mainstream (CIA or Cuban involvement) to the bizarre (UFO cover ups

Now, there’s a new twist in the tale. Last week, after six decades of silence, a key witness revealed new information that casts further suspicion on the “official” account of JFK’s murder. In an account that also features in a forthcoming memoir, ex-secret service agent Paul Landis – who was detailed to Jackie Kennedy that day – said that he retrieved a bullet from the Kennedys’ limousine after JFK was shot and later left it on the former president’s stretcher at the hospital. It’s a seemingly tiny detail, but one that differs from the official version of events – in which the bullet was found on the stretcher of Governor John B Connally Jr, who was shot while riding in the president’s car – and further fuels the theory that the shooter Lee Harvey Oswald did not act alone.

The fascination with JFK’s death is fed by different factors. “If you think of Kennedy, then he is the iconic president for most people,” says Peter Ling, Emeritus Head of American Studies at Nottingham University, and author of the biography John F Kennedy. “He was the first television president, and the young guy with the attractive wife and the nice kids.” For a future project, Ling has been reading a fraction of the nearly two million condolence letters sent to Jackie Kennedy following her husband’s death. The correspondence – kept in the John F Kennedy Library in Boston – comes from all over the world, and demonstrates the seismic impact JFK’s death had at the time.

After JFK’s death, there was an outpouring of grief around the US and across the world (Credit: Getty Images)

There’s also the fact that this horrific event was caught on film. The Zapruder film – 26 seconds of silent 8mm footage – was captured on a home movie camera by Dallas dressmaker Abraham Zapruder, who was standing on a concrete ledge watching the president’s visit. The image of Jackie Kennedy in her pink suit, crawling across the back of the car is emblazoned on the memory of anyone who’s seen it. Zapruder has been called the first citizen journalist and the footage is credited by some as changing the limits of cinematic violence.

An enduring mystery

Most of all though, the continued fascination with JFK’s assassination is likely due to the enduring mystery surrounding it. A year after JFK’s death, The Warren Commission’s report – instructed by President Lyndon B Johnson – published its findings, which concluded that Oswald had acted alone to kill Kennedy, firing three bullets from the sixth-floor window of the Texas School Book Depositary. The second and third bullets hit the president from behind, with the third killing him. The report dismissed any notion that what happened was part of “any conspiracy, domestic or foreign, to assassinate President Kennedy” and concluded that Jack Ruby shot Oswald two days later as act of patriotism.

The assassination was captured on cameras and home-video footage – this image was taken moments before it happened (Credit: Getty Images)

It wasn’t long before doubts and questions over the report’s findings arose – which have only intensified over the years. “Part of the problem with the Kennedy assassinations that we never actually got to hear Oswald’s side of the story,” says Ling. “You had someone who seemed to be the culprit, even though he protested his innocence, but he never went to trial.

In a fiercely divided country, Americans largely agree on one thing… there’s more to the JFK killing than they know. A 2017 survey found that 61% believe others were involved in the assassination.

This uncertainty – and continued interest from the public – has proved fruitful for writers, directors and artists. An estimated 40,000 books have been published about Kennedy. This includes a slew of non-fiction titles pushing various alternative theories – including the involvement of the Russians, Castro, Cuban exiles, the CIA, the FBI and organised crime. In his 1995 book Oswald’s Tale, Norman Mailer took a deep dive into the life of the gunman.

But fiction writers have also found inspiration in the events of November 1963. Stephen King’s 11/22/63 tells the story of a time traveller who tries to prevent JFK’s assassination. James Ellroy’s American Tabloid is a fictionalised account of JFK’s death from the perspective of three rogue law-enforcement officers. Don DeLillo’s 1988 novel Libra placed Oswald at the centre of a CIA conspiracy. DeLillo spent three years researching the book and told The New York Times: ”I don’t know any more than you do what happened in Dealey Plaza that day. I purposely chose the most obvious possibility – that the assassination was engineered by anti-Castro elements – simply as a way of being faithful to what we know of history. Will we ever know the truth? I don’t know. But if someday evidence of a conspiracy does emerge, I expect it will be much more interesting and fantastic than the novel.”

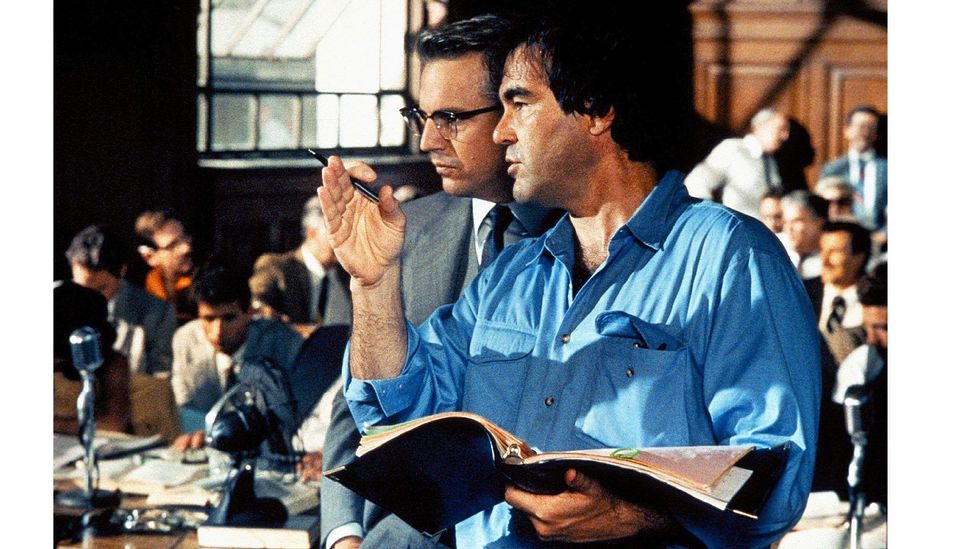

Oliver Stone’s JFK film was partly responsible for the release of previously classified documents about the assassination (Credit: Alamy)

On the big screen, the assassination shows up in various forms – from brief mentions in Stanley Kubrick’s Full Metal Jacket to inspiring entire plot lines. In 1993’s In the Line of Fire, Clint Eastwood plays fictional Secret Service agent Frank Horrigan, the man guarding Kennedy in Dallas on that fateful day. Consumed with guilt over his failure to save him, Horrigan becomes obsessed with preventing a new assassin. In 2016’s Jackie, Natalie Portman plays the first lady in the immediate aftermath of her husband’s death.

But by far the most pivotal film about the assassination is Oliver Stone’s controversial JFK. The 1991 drama landed eight Oscar nominations, including best picture, but some critics called it “dangerous” for mixing documentary footage with fictionalised drama. In Stone’s version of events, the CIA wanted Kennedy dead because he planned to deescalate the conflict in Vietnam. It’s this theory that has gathered most steam over the years – not helped by the CIA and FBI’s reluctance to release information.

“There’s a kind of psychological dynamic here in that we tend to remake our memories to make sense of how things have gone,” says Ling. “And so the Kennedy assassination becomes seen as this moment when the hopefulness of the 60s starts to falter. By the time Oliver Stone comes out and basically says [Kennedy] is killed by the CIA to enable the Vietnam experiment to go forward, that’s what many Americans sort of want to believe – that it’s all been taken away from them by evil forces.”

In 1992 – partly as a result of Stone’s film – US Congress passed the John F Kennedy Assassination Records Collection Act, leading to the release of millions of previously classified documents about the assassination. They have been released in batches – Biden authorised release of the final batch this year – and every new burst of information feeds the frenzy further.

Paul Landis’s shocking new revelation, which comes from his upcoming book The Final Witness, set to be published on 10 October, is sure to shake things up even further.

“It’s fundamental in what it blows out of the water,” says Ling. Because the bullet was found on Connally’s stretcher, the Warren Commission originally concluded that a single bullet travelled through Kennedy and hit Connally, causing several injuries. It became known as the “magic bullet” – but many were doubtful one bullet could behave this way.

“If it didn’t go through in that way we are left with unanswered questions as to where the bullet is that hit Connally,” says Ling. “If we start getting more bullets than we can reconcile with the speed of fire that Lee Harvey Oswald could maintain, we’re in a situation where there has to be somebody else shooting.”

Ling though, has doubts about the credibility of this new information. There are questions over why Landis waited so long to reveal it (he says he avoided anything about the assassination for years), and it’s certainly stirred up interest in his book. In a piece for Vanity Fair, historian James Robenalt says he believes Landis. He has called the findings “the most significant news in the assassination since 1963.”

It’s too soon to tell where this new information will lead, but one thing is certain: it won’t stop people coming up with theories on what happened that day. “It’s a whodunnit that everybody knows,” says Ling. “But no-one has the final chapter.”