However, Fellini’s film doesn’t simply portray the director in his moments of being the big man on set. Instead we have access to Guido’s dreams, as he is revisited by his dead parents, has visions of memories from his school days, and even imagines a fantastical harem where all of his previous love affairs and sexual conquests reside and eventually rebel against him. He is shown to be a deeply flawed, even troubled person, lacking the confidence his crisp suit suggests. But it’s a warm admission, with Fellini being refreshingly vulnerable in his openness.

In the end, the situating of a sincere, tender autobiography in such a cool, empty milieu raises questions as to what is real and what is fantasy. After all, two such differing worlds do not sit naturally together. “What I love about Fellini is that he was a liar,” Gilliam said in his original Close-Up interview, discussing in particular the portrayal of filmmaking. “He’s a constant liar. He twists and distorts the truth.” He elaborates further on this point today. “Fellini was a great liar and yet his lies were very close to the truth,” he adds, and in fact “a better truth than the facts!” His point being that filmmaking is such an absurd and surreal venture in the first place that it may as well be a strange dream.

Fellini’s world is still an illusion. As with magic, the film is a stylish sleight-of-hand, but the human reaction it inspires is very real and potent. “He took me down these passages,” Gilliam concludes “these ways of looking at the world and this is what I thought films were supposed to do, and many films just didn’t. He broke every rule there was to break. All the things you’re not supposed to do he did, and he made it all work!” Throwing away the cinematic rulebook was a radical but undeniably cool look.

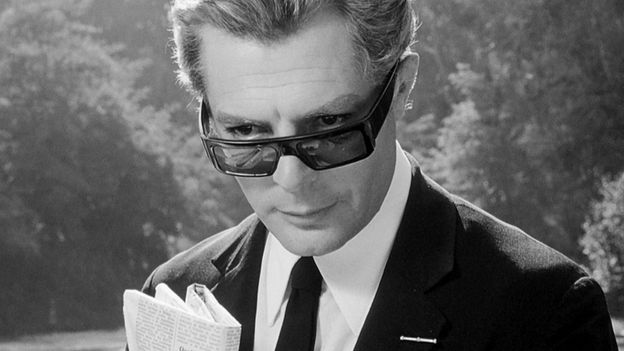

But Fellini’s film ultimately shows that what matters is the beating heart beneath the modish exterior – and it is perhaps its air of fallible humanity, alongside its distinctly timeless style, that means Fellini’s film still feels cool today. If there was nothing beneath the sunglasses – Guido’s being an iconic pair of Prada SPR 07F like any good European jetsetter – then 60 years on, the film would surely ring hollow. 8 1/2 is arguably as much a portrait about simply being alive as it is about creativity. Perhaps Fellini’s final trick is portraying life as a kind of film of our own making, one we slip in and out of like a dream. And what illusion could really be cooler than that?