Once upon a time a small orphaned boy was packed off to live with his aunts. They were a sadistic pair, these sisters, and rather than console and nurture they bullied and beat and half-starved him. But he got his revenge, literally crushing them as he finally escaped, bound for adventure and a better life. It doesn’t sound much like the set-up of a bestselling book for children, but what if I told you that the boy’s getaway vehicle was a gargantuan fuzzy-skinned fruit?

Read more about BBC Culture’s 100 greatest children’s books:

The 100 greatest children’s books

Why Where the Wild Things Are is the greatest children’s book

The 20 greatest children’s books

The 21st Century’s greatest children’s books

Who voted?

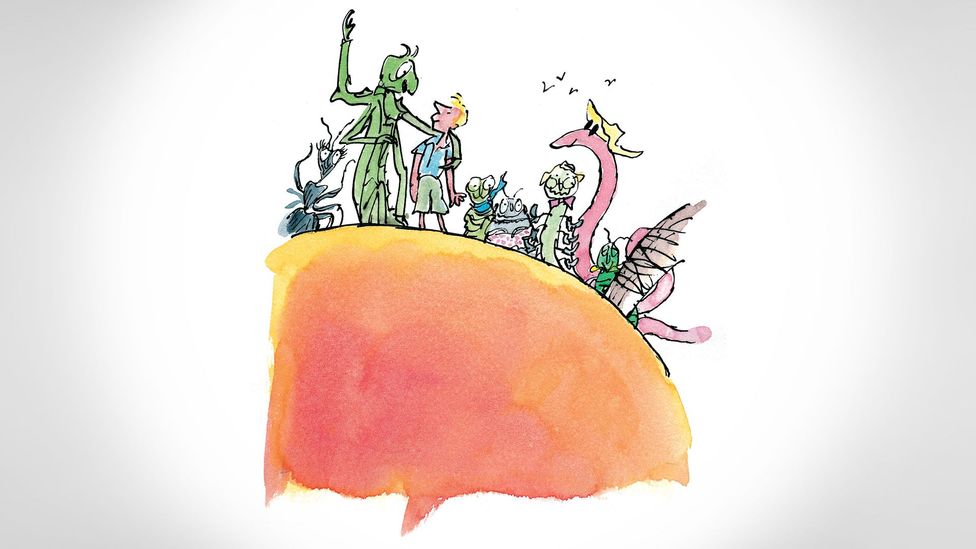

James and the Giant Peach sprang from bedtime stories Roald Dahl told his daughters. It was his first work for children but had the same effect on plenty of adult readers as the short stories that had already earned him a modest literary reputation – twisted tales with grisly punchlines, published in magazines including The New Yorker and Playboy. So troubling did the book seem that while it was published in the US in 1961, Dahl had to wait until 1967 before it appeared in his native UK, and even then found himself compelled to sign away royalties until production costs had been recouped. (He’d then receive a very generous 50 per cent of any profits, making it seem a savvy-seeming deal after successive print runs sold out.)

James and the Giant Peach was the first of Dahl’s works for children – and it left plenty of adult readers disturbed (Credit: Illustrations © Quentin Blake)

He followed it with more than 15 other books for children, stories bursting with gluttony and flatulence, in which wives feed their husbands worms and the young are eaten by bone-crushing giants and changed into rodents by be-wigged, toeless hags. Villains loom large; as mean as they are ignorant, they tower over pint-sized if plucky protagonists, twirling them around by their pigtails or banishing them to places like “the Chokey”, a nail-studded punishment cupboard.

Today, titles like Fantastic Mr Fox, The BFG and Matilda, which was released just two years before his death aged 74 in 1990, regularly appear on lists of the best children’s books ever – including BBC Culture’s own. Collectively, his books have sold more than 300 million copies worldwide, their stories also spawning stage and screen adaptations, including a recently announced prequel to Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, set to star teen crush Timothée Chalamet as a young Willy Wonka.

Taking offence

The controversy has never gone away though. In the decades since its publication, James and the Giant Peach alone has been lambasted for its references to drugs and drink (all that snuff and whiskey), profanity (“ass” is used several times), and sexual innuendo (a scene in which a spider licks her lips got readers in Wisconsin hot under the collar), not to mention its alleged promotion of disobedience and – wait for it – Communism.

While those complaints might smack of puritanical alarmism, take a closer look at Dahl’s writing for children, and you’ll find something to offend almost everyone. If he was a bigot, he was an equal-opportunities bigot. James’s pal the Grasshopper at one point announces: “I’d rather be fried alive and eaten by a Mexican.” Female characters tend to be either warm or wicked with nothing in between, while Revolting Rhymes brands Cinderella, that fairytale girl-next-door, “a dirty slut”. Teachers tend to be villainous, and even when benign, fail to impart much real wisdom.

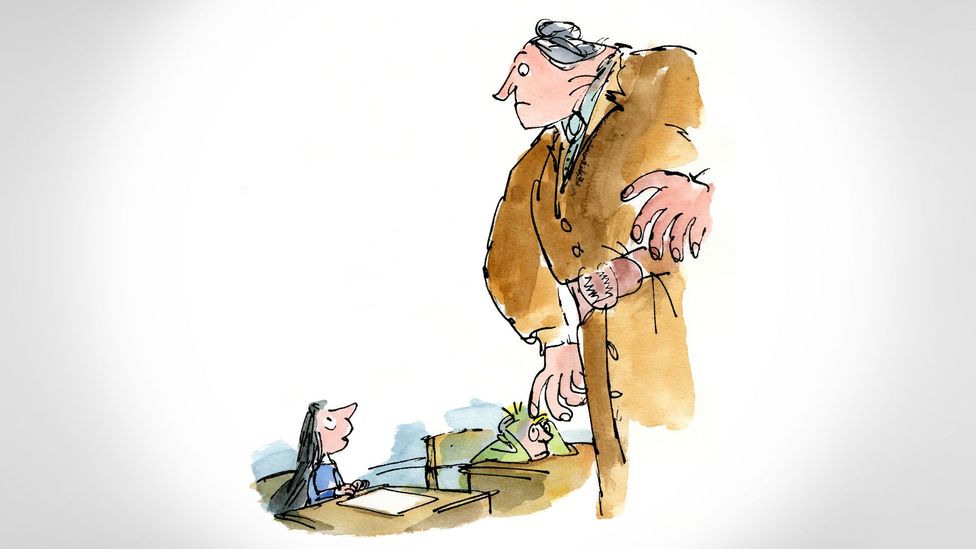

Titles such as Fantastic Mr Fox, The BFG and Matilda regularly appear on lists of the most popular children’s books ever (Credit: Illustrations © Quentin Blake)

Unsurprisingly, Dahl’s writing for children has frequently been the subject of book bans, but jumpiness around his work is also manifesting on the opposing side in the culture wars. Earlier this year, it emerged that in the 2023 editions of his books, publisher Puffin had changed hundreds of potentially offensive words relating to race, mental health and physical appearance. The originally “enormously fat” Augustus Gloop from Charlie and the Chocolate Factory is now simply “enormous”; “ugly and beastly” Mrs Twit is merely “beastly”; and the “crazy” glow worm that James voyages with is plain “silly”. Elsewhere, the BFG no longer has “flashing black eyes”, they’re just “flashing”, and in The Witches, a particularly clunky sentence has been added to explain that while the supernatural women in question wear wigs to conceal their bald heads, “There are plenty of other reasons why women might wear wigs and there is certainly nothing wrong with that.”

It should be noted that Dahl himself did make changes to Charlie and the Chocolate Factory’s Oompa Loompas, who were originally depicted as black pygmies from “the deepest and darkest part of the African jungle”. Posthumous changes have also been made to the work of other authors – Enid Blyton’s Fanny and Dick are today Frannie and Rick, while her maniacal Dame Slap has become Dame Snap, yelling rather than doling out corporal punishment.

Even so, the fierce outcry provoked by Puffin’s textual tampering was instantaneous, coming from quarters as varied as Britain’s then Queen Consort, who urged authors to resist curbs to their freedom of expression, and Salman Rushdie, who decried Puffin’s actions as “absurd censorship”. In its defence, the publisher insisted that the changes were necessary to ensure the works’ ongoing relevance.

Charlie and the Chocolate Factory’s Oompa Loompas were originally depicted as small black pygmies with warlike cries (Credit: Illustrations ©Quentin Blake)

Literary vandalism, commercial pragmatism, a genuine desire to safeguard newly independent readers – or some combination of all of the above? The debate quietened only after it was announced that while the new editions would stand, the original texts would also be made available, packaged as “the Classic Collection”.

The intensity of the furore testified in part to the place that Dahl’s children’s books have found in the hearts of generations of young readers around the world. There’s no denying he knew just what his juvenile readership liked – and continue to like: chocolate, magical powers over beastly grownups, and – to borrow some Gobblefunk, the language he invented for his Big Friendly Giant – the kind of filthsome, frightsome fare that makes kiddles squirm with gleeful revulsion.

“Children love disgusting stories,” Maria Nikolajeva, professor of education at the University of Cambridge, told BBC Culture in 2016. The revolting serves “an important cognitive-affective function: we know it’s disgusting, and the knowledge makes us superior. It’s healthy. But it must be disgusting in combination with humour. Because extreme violence is not healthy. But Dahl is never violent, not even with naughty children in Charlie and the Chocolate Factory,” she goes on.

Villains like Matilda’s Miss Trunchbull loom large in his books, towering over pint-sized protagonists (Credit: Illustrations ©Quentin Blake)

Dahl, Nikolajeva believes, “is one of the most colourful and light-hearted children’s writers”. But for all the funniness and dazzling linguistic acrobatics of his prose, she acknowledges that there are problems with his vision. Consider Charlie and the Chocolate Factory. “Wonka is vegetarian and only eats healthy food, but he seduces children with sweets. It’s highly immoral,” she says. And then there’s The Witches, whose child narrator, having been turned into a mouse, decides against returning to his human form because he dreads outliving his beloved grandmother. He’d rather die with her, as his abbreviated rodent lifespan will guarantee. “This is a denial of growing up and mortality, but mortality is one of the aspects that makes us human,” Nikolajeva points out. “To tell young readers that you can escape growing up by dying is dubious – drawn to the utmost, an encouragement of suicide – and therefore both an ideological and an aesthetic flaw”.

Darkness, for want of a better word, has forever been a secret – and not so secret – ingredient in children’s literature, whether it’s tales by the Brothers Grimm and Heinrich Hoffmann, or Lord of the Flies and The Hunger Games. If you’ve ever paid attention to the words of a nursery rhyme like Ring a Ring o’ Roses or Oranges and Lemons, you’ll know that suckling babes are reared on the stuff – and with good reason. As child psychologist Bruno Bettelheim explained in his seminal study, The Uses of Enchantment, the macabre in children’s literature serves an important cathartic function. “Without such fantasies, the child fails to get to know his monster better, nor is he given suggestions as to how he may gain mastery over it. As a result, the child remains helpless with his worst anxieties – much more so than if he had been told fairy tales which give these anxieties form and body and also show ways to overcome these monsters,” he wrote.

Light and shade

It’s not hard to see where Dahl might have drawn his own darkness from. Having lost his older sister and father when he was three years old (his sister to appendicitis, his father to pneumonia), he was packed off to boarding school aged just nine. The first volume of his memoirs, Boy, recalls in great detail the headmaster’s penchant for floggings so vicious they drew blood.

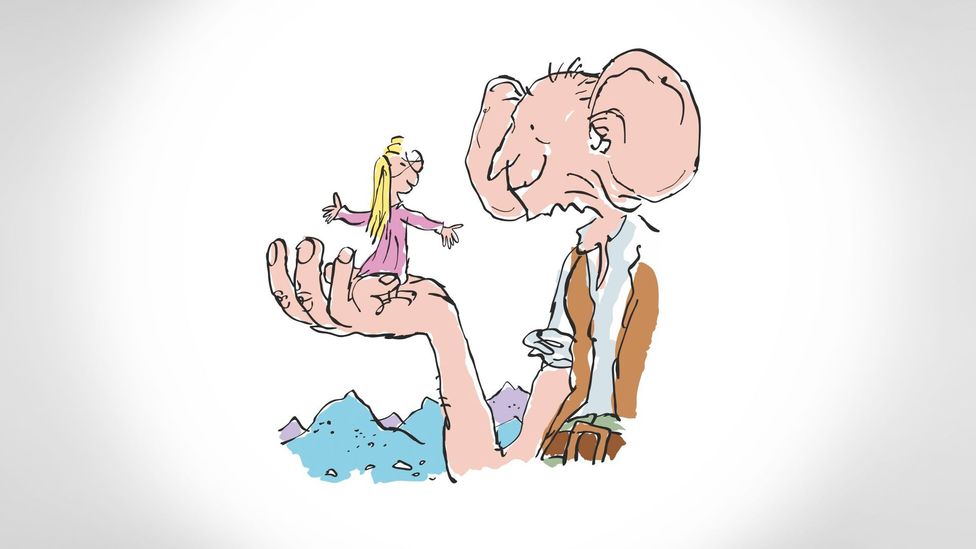

As a young RAF pilot in World War Two, Dahl came close to dying. Invalided out after crash landing in the Western Desert, he subsequently spent time in the US, seducing heiresses and wealthy widows in the name of counterintelligence. His long first marriage, to the actress and celebrated beauty Patricia Neal, had far from a storybook ending. The couple lost their eldest daughter to illness, and their only son was left brain-damaged by a traffic accident. A few years later, Neal herself suffered a series of strokes while pregnant with their fifth child. Relearning how to speak in recovery, she would come out with language that inspired the BFG’s lexicon.

Dahl invented his nonsense language, Gobblefunk for The BFG (Credit: Illustrations ©Quentin Blake)

It was Neal who coined the nickname “Roald the Rotten”, referring to a mean, dyspeptic streak of which she saw plenty. He cheated on her, and his years-long affair that would eventually end their marriage was with a friend of hers. He could be a thoroughly unpleasant man outside the home, too. Despite his towering success, he was chippy about being a children’s author. And he made no attempt to hide his anti-Semitism. In 1983, he announced in the New Statesman that Hitler had his reasons for exterminating six million men, women and children. “There is a trait in the Jewish character that does provoke animosity,” he said. “I mean, there’s always a reason why anti-anything crops up anywhere; even a stinker like Hitler didn’t just pick on them for no reason.”

Read enough along these lines (there’s more out there) and the sprightly horror of Dahl’s narratives no longer slips down quite so easily. That’s what the British Royal Mint found in 2018, when it decided against issuing a commemorative coin to mark the 100th anniversary of his birth, noting in its minutes that Dahl was “associated with anti-Semitism and not regarded as an author of the highest reputation”. (In 2020, three decades after his death, the Dahl family did issue an apology, quietly posted on the official Dahl website, for the hurt caused by his anti-Semitic statements.)

Should we let this ruin his writing for us? Nikolajeva is unequivocal: “Frankly, I don’t care about writers as real people,” she told BBC Culture in 2016. “If Dahl had been a sweet, benevolent storyteller would he have survived at all? Who wants sweet, benevolent stories?” Certainly not children, it would seem.

There was undoubtedly an element of provocation in much of his nastiness, both on and off the page. As the lives of the likes of Lewis Carroll, Margaret Wise Brown and CS Lewis illustrate, to write brilliantly for children, an author must retain an element of the childlike. Sometimes, that blurs into childishness – to quote Dahl himself, a children’s author “must like simple tricks and jokes and riddles and other childish things”.

But it’s also worth recalling this: while used differently, both childish and childlike essentially refer to qualities associated with children. And as the peerless Maurice Sendak observed, “In plain terms, a child is a complicated creature who can drive you crazy. There’s a cruelty to childhood, there’s an anger.” If Dahl’s books contain just one message for us wary adults, it’s the reminder that a child’s world can never be all sweetness and light, it contains shadows too – shadows that, when the child protagonist, and by extension reader, is sufficiently empowered, become extravagantly scary and wickedly entertaining.

Read more about BBC Culture’s 100 greatest children’s books:

The 100 greatest children’s books

Why Where the Wild Things Are is the greatest children’s book

The 20 greatest children’s books

The 21st Century’s greatest children’s books

Who voted?