In August 1977, the police arrived at 284 Green Street in the north London suburb of Enfield. Peggy Hodgson, a single mother of four, reported that her two young daughters – Janet, aged 11, and older sister Margaret – had heard strange knocking. The source of the sound could not be determined. They called in the neighbours who were also disturbed by what they heard. Out of desperation, they rang the police, one of whom reportedly saw a chair move of its own accord. Next, they turned to the press.

More like this:

– Why The Exorcist taps into our darkest fears

– The terror of the Australian outback

– The cinematic power of the ‘eerie’

Over the next 18 months, stories of increasingly strange phenomena emerged from the house. Furniture was hurled across the rooms, there were reports of “paranormal whistling” and, most unsettling of all, Janet Hodgson was heard to talk with the rasping voice of an old man. The case came to the attention of the Society for Psychical Research (SPR), and two of its members, inventor turned paranormal investigator Maurice Grosse and writer Guy Lyon Playfair, were sent to investigate. Playfair would later publish a book, This House is Haunted, about his experiences.

A new Apple TV+ docudrama is the latest work to retell the story of The Enfield Poltergeist (Credit: Apple TV+)

Eventually events in the house just stopped but not before Janet spent time in London’s Maudsley psychiatric hospital. She is still clearly affected by happenings in the house. “I know what I experienced. I know it was real,” she says in a new Apple TV + four-part drama-documentary series about the phenomenon. “It follows you. It has never left me.”

In the years since, the events in that Enfield council house have remained a source of fascination. There have been numerous retellings and adaptations of the so-called Enfield Poltergeist, including a 2015 TV drama, The Enfield Haunting – which starred Timothy Spall as Grosse and a pre-Succession Matthew Macfadyen as Playfair – and Hollywood blockbuster The Conjuring 2, which dispatched its lead duo, American paranormal investigators Ed and Lorraine Warren, to North London.

Why it’s back in the spotlight

Now a new play about the bizarre phenomenon written by Paul Unwin, creator of long-running UK medical drama Casualty, and starring Catherine Tate and David Threlfall, is set to premiere. Also called The Enfield Haunting, it will open in London’s West End in November. Meanwhile the Apple TV+ series painstakingly recreates the interior of the Green Street house, and weaves together visual enactments of audio recordings made by Grosse at the time and interviews with people who were there.

Unwin’s interest in the case began 11 years ago when he was introduced to Playfair, as they shared an agent. “I met this extraordinary man, who told me this very peculiar story,” he tells BBC Culture. Unwin visited the writer’s basement flat in Earls Court and Playfair played him some of the tapes he’d recorded in the house. At first Unwin was unconvinced – it sounded to him like children shouting and playing games – but the more he listened, the more questions he had.

He has his own ideas about what happened in the house. The story of the Enfield haunting can be understood on different levels, he explains. It’s important to remember, he says, that the late 1970s was “quite an odd, intense period”, with the UK in political and economic turmoil. The family had just gone through a divorce and were living in considerable poverty, so he understands how two young girls might become possessed by the circumstances in which they found themselves, swept along by events that quickly became bigger than them. “Emotions are not simple,” he says. “It can be very easy to become committed to stuff that isn’t necessarily true.” He makes a connection between what happened in Enfield and the anti-vax and QAnon movements. However, he adds, he does not discount a supernatural explanation for at least some of what went on there. There are some things about the story, he says, that “really don’t make sense”.

Unwin stresses that his play is not a documentary. “It’s an imagined response to those events.” The play is a taut 90 minutes and takes place on one night in 1978, after events had been going on for some time. “I’ve aligned a lot of things that happened over a period into that one night because it makes for good theatre,” he explains. His primary goal was not to spook an audience but to present a “deeper exploration of what was going on, to show the forces at work”.

At the same time, he is very conscious of the fact that, intentionally or otherwise, there was a degree of exploitation of the young girls in the Enfield case. “I didn’t want to be another male exploiting them,” he says. “In my exploration of the story, I tried to find an emotional truth for me and things that have happened in my own life.”

The impact it left

Why has this story proved so culturally enduring? “Enfield is the archetypal British haunting,” says Stephen Volk, writer of the iconic 1992 BBC show Ghostwatch, a faux-reality TV show which was in part inspired bv The Enfield Poltergeist. The familiarity and normality of the setting, with a normal working class family in a normal house, not a stereotypical haunted mansion, made it more resonant. “It wasn’t a Hammer Horror castle,” he says. “There were no clanking chains.

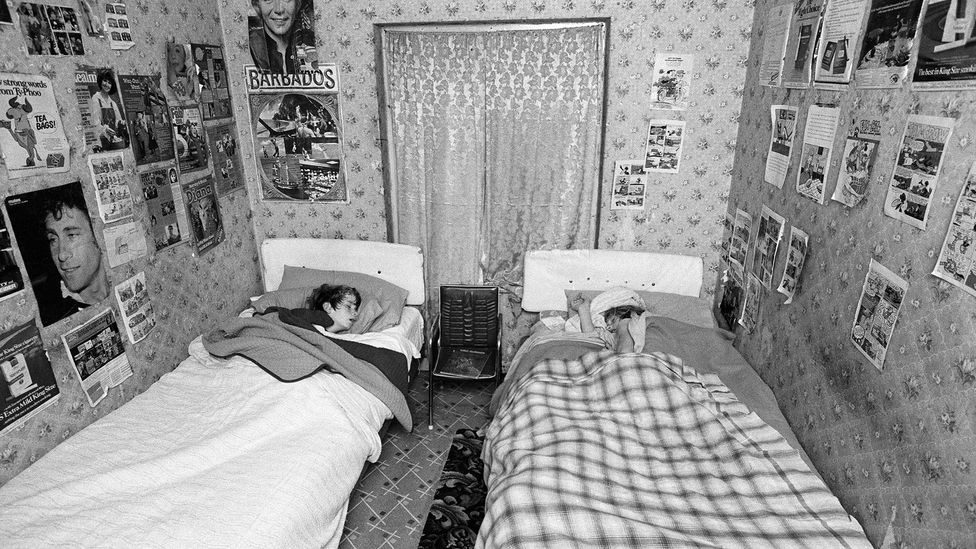

The Hodgson sisters’ bedroom, where many of the strange happenings occurred (Credit: Alamy)

In the 1970s, he explains, with films like The Exorcist, horror was beginning to shift into more recognisable domestic spaces, in the US at least. “There was more to relate to in Stephen King’s Maine than in a lot of British horror.” However the events in Enfield echoed this new US model, taking place in a house that, he says, “could easily be around the corner”.

Though pre-recorded, Ghostwatch was presented as a live on-air investigation into mysterious events at the London home of the fictional Early family, with real-life television presenters including Michael Parkinson and Sarah Greene hosting the show and adding to the sense of veracity. “I read everything I could get my hands on in terms of ghosts and hauntings, and formulated what I thought was a kind of an archetype of the way these things work,” he says.

“It seemed incumbent on me to create a kind of fractured family,” says Volk, though the family dynamics were based not on the Hodgsons, but on the Fox Sisters, 19th-Century mediums who convinced people that they were communicating with spirits via strange rapping noises.

Ghostwatch terrified audiences and resulted in outraged headlines in the tabloids, though it has since become a cult favourite. It was watercooler television before the term entered the lexicon, and subverted the rules of reality TV before they’d been established. Playfair was credited as “psychic consultant”, and members of the SPR manned the phone lines that the audience was invited to call (at which point they were informed the show wasn’t real), But the organisation was not overly pleased with the resulting show, which they felt trivialised the science of parapsychology. For children watching at the time, however, it was seminal television, and says Volk, “television is a kind of a haunting. It’s full of people that don’t exist anymore”.

What really happened?

The Apple TV+ documentary shows that while Grosse and Playfair were convinced that there was something otherworldly going on at 284 Green Street, other members of the SPR were harder to convince, including Anita Gregory, a lecturer in psychology, who speculated that the presence of Grosse, Playfair and the media was contributing to the situation.

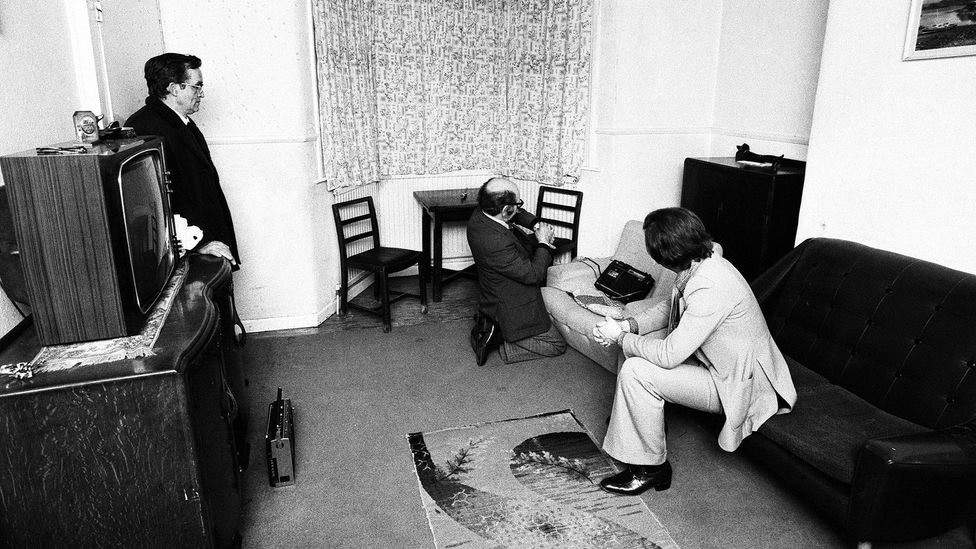

Paranormal investigator Maurice Grosse (pictured centre) spent months at the house, making audio recordings among other things (Credit: Alamy)

Deborah Hyde, editor-in-chief of The Skeptic magazine, which promotes “science and critical thinking”, says we shouldn’t underestimate the role that facilitators like Playfair played in both shaping the story and legitimitising it. Usually a facilitator is an educated, articulate man of a certain class background who has a stake in the story, she explains. “There was a very clear facilitator in the case of the Fox sisters as well,” she adds. “And when they get involved, the story gets out of hand because it can get transmitted to other places.”.

In 2011, Hyde appeared on This Morning alongside Playfair and Janet Hodgson, in one of the latter’s rare public appearances. Hodgson, Hyde believes, would undoubtedly have been better off if she could have left that chapter of her life behind long ago, but “she wasn’t able to because Playfair’s identity depended on it”. Playfair subsequently passed away in 2018, but the story has not died with him: Hyde ultimately believes the reason writers and documentary makers keep returning to Enfield is “because it’s easy to sell an existing IP.”

“Enfield is part of the cultural fabric of the UK,” says Danny Robins, broadcaster, playwright and creator of the hit supernatural podcasts Uncanny and The Battersea Poltergeist, who is now also presenting a TV version of Uncanny on BBC2. “I can’t remember when I first encountered the story. I feel like it’s always been in my memory,” he tells BBC Culture.

Part of the reason Enfield has proved so durable is because of the sheer volume of evidence we have of the case, Robins says – not just Grosse and Playfair’s recordings but stills and audio footage from Daily Mirror photographer Graham Morris and the producers of the BBC radio documentary made at the time. Numerous eyewitnesses described items flying through the air and matches that spontaneously burst into flames. Morris himself described being hit by one of those objects. Robins interviewed Morris about his experiences for the first episode of his Uncanny TV show. “He was there at the beginning, capturing images, and recording his own experiences, which are quite incredible.”

The BBC’s infamous 1992 faux-supernatural investigation show Ghostwatch borrowed the Enfield Poltergeist’s British suburban setting (Credit: Alamy)

“There’s a huge amount of evidence there, which is something that is normally absent from paranormal cases,” says Robins. While people have referred to Enfield as one of the UK’s most credible hauntings, he says, “there’s a case to be made that it’s just the most photographed”.

The case also took place at the “sweet spot”, in Robins’s words, when there was a lot of public interest in ghosts, UFOs and other unexplained phenomena, and when newspapers also had the resources to send journalists to investigate these cases. There was also a degree of public trust in the media that led the Hodgsons to call the paper for help.

In general, when it comes to the supernatural, Robins is neither believer nor sceptic, but approaches every case with an open mind – as he does, too, the Enfield Poltergeist. “Enfield is a really murky, complicated and deeply intriguing case,” he says. Though Grosse and Playfair had, he feels, the best intentions, “their presence certainly created a very heightened sense of drama around it”. But despite this, the case is “clearly robust enough to deflect sceptic inquiry”, he believes – for while there have been many convincing sceptic theories on it, “none [has been] significant enough to completely debunk it in the same way that the Amityville haunting has been debunked in the US”. Enfield remains culturally resonant, Robins concludes, because “it retains its mysteries”,