He was just a boy, but he came to epitomise male beauty. His fame was such that he was forever known simply as “David”. The humble shepherd boy who slayed the Philistines’ most formidable warrior, the giant Goliath, and was later crowned king of Israel, has been the subject of some of art history’s most iconic works. Italy’s finest sculptors − Donatello, Verrocchio, Michelangelo and Bernini − all broke the mould with their Davids, while painters such as Guillaume Courtois, Rubens, Reni, and Carav aggio created emotive masterpieces of him in oil.

More like this:

– Hidden symbols in Vermeer’s paintings

– Striking images of ignored Americans

– Britain’s most chaotic traditions

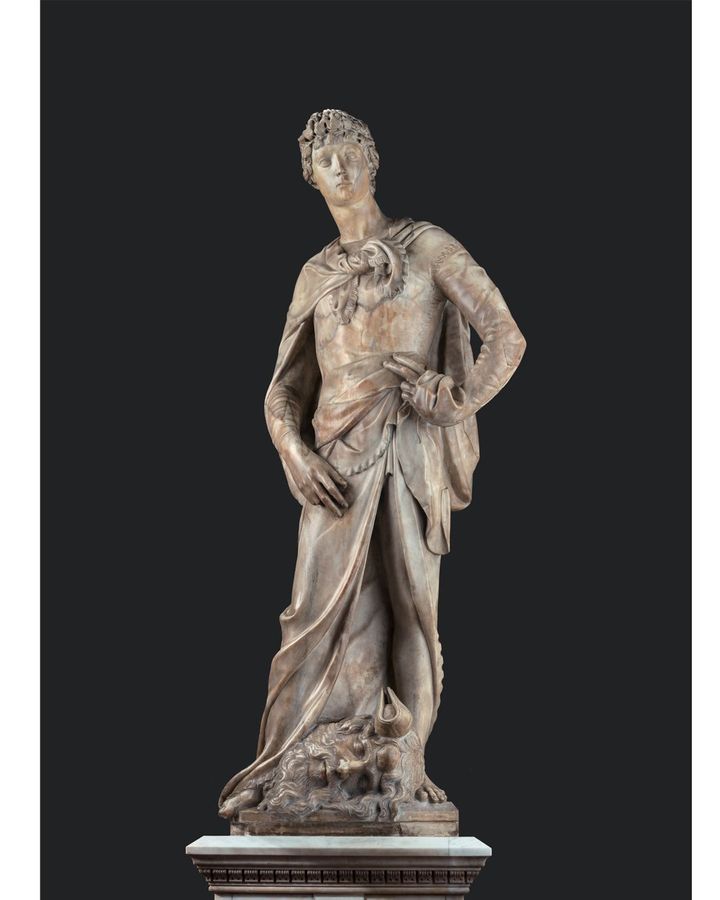

Described in the Bible as having “beautiful eyes and a handsome appearance”, his dramatic story and good looks made him the perfect muse. The figure of David first won hearts in Florence in 1408 when Donatello di Niccolo di Betto Bardi, barely more than a boy himself, sculpted in marble a youthful and victorious David with Goliath’s severed head at his feet.

Caravaggio’s emotive masterpiece in oil, David with the Head of Goliath (1610) (Credit: Alamy)

With the recent opening of Donatello: Sculpting the Renaissance at London’s V&A, the masterpiece comes to the UK for the first time, joining a copy of Donatello’s second and better-known David, cast in bronze 30 years later, and part of the museum’s permanent collection.

The marble David’s lifelike, shapely body and slightly twisted pose marked a departure from the rigidity of medieval sculpture and was an early sign that, with Donatello’s groundbreaking mastery of this challenging medium, the Renaissance mission to revive the knowledge and beauty of classical antiquity was on the right path.

If we admire the boy’s beauty, it is due in part to the unusual humanity in Donatello’s work. “Although idealised, the young hero has a sense of the individual,” Peta Motture, lead curator for the V&A’s Donatello exhibition, tells BBC Culture. Donatello’s sculpture “adds a psychological sensitivity” and demonstrates the artist’s “understanding of the human psyche” and “innate ability to capture a moment”.

Donatello’s early marble David sculpture, 1408, is featured in the V&A’s exhibition, Donatello: Scultping the Renaissance (Credit: V&A Museum, London)

Sculpture at this time was always architectural, so when it was decided that Donatello’s marble David would not stand on a buttress of Florence’s cathedral as originally intended, but instead in the City Hall, a new role for statues as popular and political was etched in art history.

Removed from the church, David was no longer just a religious character, but became an allegorical figure for another underdog: Florence. Against the odds, the small city state had overcome aggressors from neighbouring territories. “The gods give support to the brave fighters for their fatherland against even the most fearsome enemies,” reads a Latin inscription beneath the sculpture.

Donatello’s return to the subject of David in the late 1430s resulted in the first freestanding nude sculpture since antiquity. The work was unusual: not only was it a private commission (for the most powerful man in Florence, Cosimo de’ Medici), but its intended location in a villa courtyard meant it was designed to be seen from all the way around.

Represented post-battle, David stands on the head of the giant, Goliath’s mighty sword in his hand. His shepherd’s hat seems effeminate, his pose coquettish, his body childlike and his treatment of Goliath brutal. To the modern eye, it’s a work of contradictions, with David’s nudity appearing to denote both purity and desire. Some critics speculate that Donatello, a homosexual living in a place and time where young boys were often courted by older men, deliberately sexualises his David, while others deem this interpretation an anachronism.

Donatello’s bronze statue (1440s) of the young hero David, with the head of the slain Goliath at his feet (Credit: Victoria and Albert Museum, London)

Speaking to BBC Culture, Jason Arkles, a Florence-based sculptor, teacher and art historian, and host of the podcast The Sculptor’s Funeral, is clearly in the second camp. “There is no sexual aspect apart from his genitals are showing,” he says. “Art is nothing without context. If you don’t understand why a sculpture was made then you’re missing most of the story.” Works of art at the time were always commissioned, he stresses. “They’re not just objects of beauty or vehicles of self-expression.”

Much has been made of the sensuous feathers running up David’s inner thigh, but Arkles’s explanation, as a sculptor, is far more pragmatic: “Donatello was building an armature, the likes of which he hadn’t seen. It was bigger and had to be completely hidden within the figure itself.” The wing running up the leg simply strengthens the weakest part of the sculpture. That any artist would risk their livelihood by expressing deeply personal thoughts in a commission is highly unlikely, says Arkles. Donatello was probably just “getting over a couple of technical hurdles”, he says, “rather than deciding, with this one statue out of his entire career, to fly his flag.”

Line of beauty

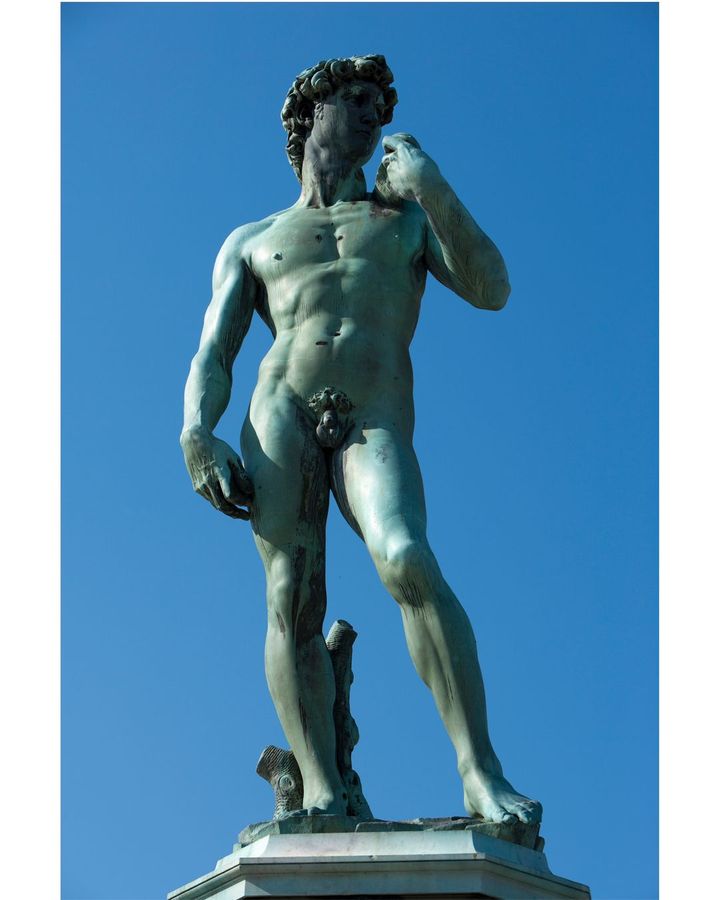

Sixty years later, Michelangelo would support his nude David in a similar place by sculpting a tree stump behind one leg in an otherwise empty tableau. Goliath has disappeared from the artwork and the boy hero, gathering his courage to do battle, commands all our attention. Where Donatello’s life-sized bronze raised eyebrows, Michelangelo’s super-sized David (1501-4), the most famous David of all, also elicited strong reactions when the marble sculpture took up a prominent position in Florence’s main square.

Michelangelo’s supersized sculpture (1501-4) is the most famous David, and came to symbolise the freedom of the Florentine Republic (Credit: Getty Images)

First the 5m-high colossus was stoned, and later a brass leaf garland concealing his manhood was hung about his waist. It is said that Queen Victoria, who was gifted a copy of the statue by the Grand Duke of Tuscany, was so affronted by its nudity that she had a fig leaf made to cover the genitalia. Today the statue resides at the V&A, along with a plaster cast of the leaf. In fact, David’s genitals may be a calculated sexualisation of the statue − his unusually small penis, a deliberate attempt to play down its sexuality.

On this same question of proportion, this paragon of masculine beauty with his thick head of hair, strong jaw and toned body is, on closer inspection, far from perfect. Not only is David’s penis too small, his hands and head are too big. Even the marble it is carved from was said to be flawed, a reject from a David begun by Agostino di Duccio under the tutelage of Donatello decades earlier.

The nude Davids were less about ideal bodies and sex appeal than demonstrating a level of artistic skill not seen since antiquity, while simultaneously celebrating the human body and the Renaissance’s growing knowledge of it. “A toga can hide a multitude of errors,” says Arkles. “When you do a nude figure, not only do you have to make all the parts, you have to make them work with all the other parts – and that was a procedural triumph.” Even when sculptor Andrea del Verrocchio clothed his bronze David in 1465, he did so translucently, continuing the trail blazed by Donatello, and showcasing the beauty and complexity of the human form.

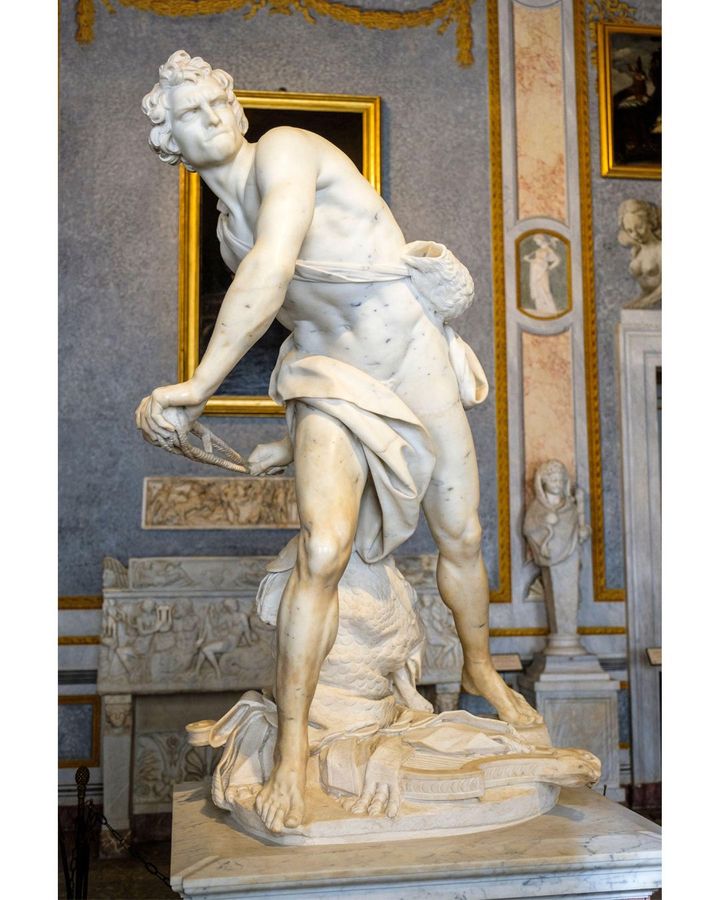

The marble sculpture of David by Bernini (1623-24) reflects the physicality and unbridled emotion of the Baroque period (Credit: Alamy)

Yet David’s physical beauty is primarily a reflection of his morality. He is beautiful inside and out: a mascot for Florence and a symbol of good government and ideal citizenship. In contrast to the unbridled emotion and physicality that we see later in the Baroque period with Bernini’s David, the Renaissance, emulating classicism, saw rationality, control and civic virtue as the mark of a man. Positioned looking fixedly and defiantly towards Rome, Michelangelo’s David embodies these qualities and came to stand for the freedom and independence of the Florentine Republic.

The statue’s symbolism was not lost on the people of Florence. “It’s almost impossible to imagine connecting to a work of art the way the Florentines connected to the David,” says Arkles. “People weren’t just moved to tears, they were moved to write poems and leave them at the foot of the statue. It became practically, for a short time, almost an object of religious veneration because of its significance.”

In a city so crammed with art treasures, it is telling that Michelangelo’s David still tops the bill. Visitors queue to see the original in the Accademia Gallery or swarm around its replica in the Piazza della Signoria. Today, Florence’s souvenir stalls heave with tawdry mementos of the popular work, just as 500 years earlier, artists creating small-scale collectables in bronze and terracotta cashed in on the prestigious subject and its winning appeal.

Contemporary artists are still finding new forms for David. A 10m-tall buddha-like gold replica of Michelangelo’s David was created by Turkish-American artist Serkan Özkaya for the Istanbul Biennale in 2005, while Los Angeles-based artist Kadir Nelson explored the idea of a black David in 2019.

A 10m-tall gold replica of Michelangelo’s David was created by Turkish-American artist Serkan Ozkaya for the 2005 Istanbul Biennale (Credit: Alamy)

Nobody knows for sure who modelled for the Davids and if the chiselled beauty of these ultimate male models ever walked the Earth in flesh and blood. It matters little. No other male figure has captured the public imagination so enduringly or been such an important vehicle for artistic endeavour.

Nevertheless, a debt must be acknowledged. “Each David has had an impact, as has each artist across the centuries,” the V&A’s Peta Motture says. “Yet each of them owes something to Donatello.”