“I’m living my life / It’s time to move on / ‘Cause there’s no guarantees that tomorrow will come.” Paul, 29, prisoner.

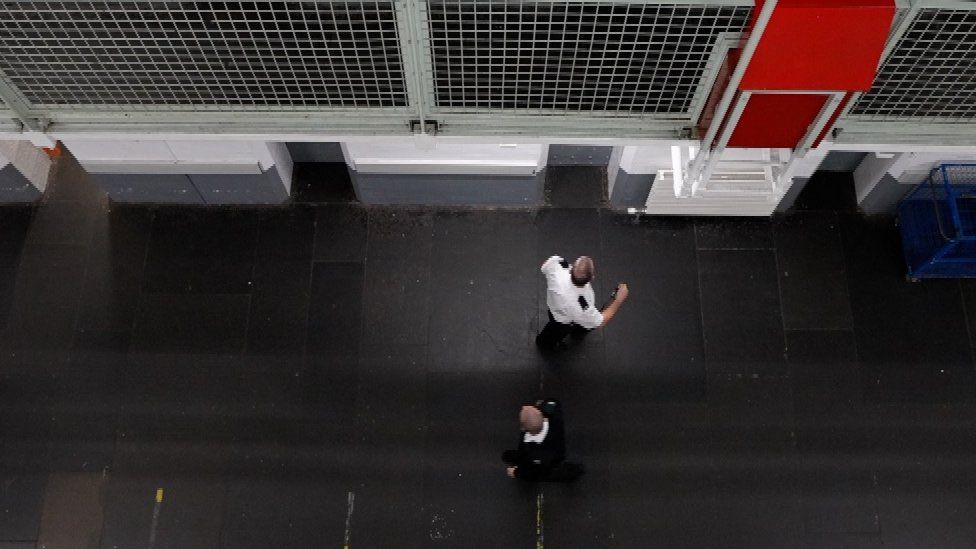

This is hip-hop made inside Barlinnie, Scotland’s largest prison and where the Lockerbie bomber Abelbaset al-Megrahi was held.

A rather ghostly reminder of his former presence are the satellite dishes, paid for by the Libyan government so that he could watch sport, which still hang off the side of the building where he was kept.

Situated in the north east edge of Glasgow and known as The Big Hoose and Bar-L, Barlinnie is more than 140 years old. The prison is to be closed as soon as a replacement is built, but that date keeps being put back.

On the bitingly cold day we visit, capacity is running at almost 145%, with 1,418 prisoners inside, when it was designed for 987.

It was against this background that Barlinnie launched its first ever hip-hop classes for prisoners. Funded by Creative Scotland, the eight-week course conceived by Jill Brown who runs Conviction Records, Scotland’s first record label for ex-offenders.

She explains: “The workshops are designed to give the guys who take part a voice, because a lot of people who are actually in jail have never had a voice. It’s really about confidence and self-esteem and dignity and people believing in you.

“But also they give people in prison something to look forward to and I always say that the poverty of hope is the worst form of destitution.”

We have been allowed behind bars, to speak to some of those taking part, although our visit was almost cancelled. The night before, Barlinnie makes the Scottish news headlines, as a prisoner managed to climb onto the roof and throw slates at guards as part of a one-man protest.

By the following morning he is back inside, and we are allowed to proceed.

First up, a visit to B Hall, where 279 prisoners are held in predominantly double cells. Over four levels with stone staircases and caged balconies, it is not hard to image exactly how Barlinnie looked when it first opened in the 1880s.

The prisoners are in a red sweatshirt if they have been convicted or a blue one if they are on remand.

Up on the second floor we are taken to the cell of Bernie. If Eminem was 32 and from Govan, this is what he would look like, and Bernie shares that he did once jump over a fence to sneak into a Slim Shady gig in Glasgow.

The tiny room is dominated by white-washed brick walls, two desks and a metal bunk bed, which he shares with his “co-pilot”.

“When I first came in, I was stuck in my cell 23 hours a day,” Bernie says, shaking his head.

“People obviously want to see people get punished, but we are getting punished. We’re in our cells. We’re already living in a prison in our head.”

Bernie is now allowed out to work in the kitchens and the hip-hop classes offer another escape, his love of Snoop Dogg and Tupac demonstrated by small computer printout posters of the rappers on his cell wall.

He has been in Barlinnie since Boxing Day last year: “I was running about breaking into businesses to fund my habit. Things that I would never normally do. That isn’t me as a person, but that’s where taking hard drugs took me.”

Back in his early 20s, Bernie had a bit of a following locally as a rapper, DJing on community radio. Being allowed to work on a new track with a real producer has given him a boost: “It keeps me good as it’s something I love doing,” he explains.

“You can do positive things with music. It’s helped bring my confidence back.”

It is time for us to head to today’s workshop and somewhat surprisingly Bernie suddenly pulls out an acoustic guitar from under his bunk, before being escorted by guards to the Wellbeing Centre, an area of the prison which hosts rehabilitation programmes.

Daddy’s Girl

Here, the musician Becci Wallace is waiting to work with Bernie on his track, a rather delicate and heartfelt tribute to his daughter, called Daddy’s Girl. He strums the guitar and softly delivers the lines:

“I remember the day you were born, the moment you came out the womb / And there was you, me, and my gran inside the room.”

This kind of lyrical honesty is exactly what Wallace believes the sessions can achieve: “My hope is that, for some of the guys at least, it might be the first chance they’ve had to be vulnerable in a safe space.

“And that actually the long-term benefits of that for them is that rather than reacting quickly and sometimes negatively in difficult situations, that they will remember that they have the ability to work things out.”

And Becci has a message for those who are not in favour of free music classes being given to convicted criminals: “If they are continuing to make the same mistakes over and over again and coming back here, then why not try something new?”

One serial reoffender taking part in the workshops is Robert from Kilmarnock who is 29 and currently serving a sentence of just under three years. He believes that the hip-hop classes can bring about change in his life.

For the last two months he has been working with Becci on his track Time, with lyrics which share his fears about the future: “Sometimes I think it is all fate? / Will I die young like half of my mates? / I’ve been numbing the pain, but the pain still hurts.”

“It’s gave me something to look forward to,” he says about the workshops.

“And it’s something I’m going to follow up on when I’m out. It’s came at the right time It’s gave me a chance.”

And could it really help him stop reoffending?

“Aye. 100% aye,” he nods insisting that he has more hope for when is released this time, than ever before.

Hip-hop showcase

The culmination of the hip-hop workshops was a small showcase, where recordings of their songs were played to an audience made up of other prisoners and guards.

On the day, Bernie decided that his track about his daughter was not completed, so instead made a last-minute recording of some old angrier lyrics he had written, laying them down over a Dr Dre style beat.

The song, called Hate These Streets, is well received and Bernie is a very relieved man. He dreams of putting his music up on YouTube once he is released: “That will help me stay out of trouble, help me focus, more positive energy and less negative energy.

“I’m changing my life for the better now and I’ve got high hopes that I’m going to be alright.”

And for Robert having his music played in front of an audience was a big moment.

“It’s gave me hope man, so it has. It’s gave me a lot of hope. This time in prison I’ve turned it into a positive, so I have.”

The workshops will be returning in 2024, but with a twist. Before we depart the organiser Jill Brown explains: “Hip-hop tends to appeal to the younger contingent, and a lot of the guys are singer-songwriters, so we have decided to give an alternative next year.”

Yes, in 2024 hip-hop will be having a rest and the beat of Barlinnie will be folk music.

Related Topics

- Hip-hop

- Glasgow

-

How hip-hop spread from the Bronx to the world

-

11 August 2023

-