Emmanuel Lafont/ KonMari Method

Emmanuel Lafont/ KonMari MethodHer best-selling book The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up was a global phenomenon, changing our thinking about material excess. Lifestyle and decluttering star Marie Kondo tells the BBC about the KonMari method, magic, minimalism and how being a Shinto maiden shaped her.

It was October 2014 when the buzz started, online and in print – a whisper that was about to go viral. There was a Japanese author, a diminutive woman with a quiet, charismatic presence. And her debut book, intriguingly, was about one of the most mundane subjects imaginable: tidying up.

Alamy

AlamyAn early review described the book’s author as “like a kind of Zen nanny”. Examining her “obsessive” techniques for decluttering helped the writer of the article discard two vast bags of “miscellaneous garbage” from their home, but the tongue-in-cheek tone of the story seemed to be asking “Can we take this person seriously?”, a message reinforced by the mocking headline: Kissing Your Socks Goodbye.

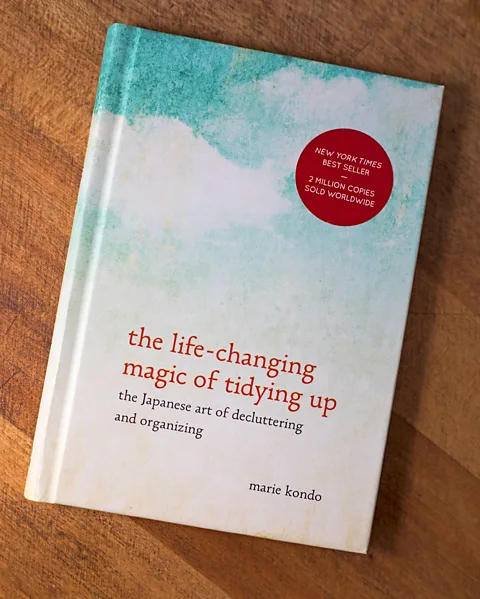

No one would have guessed the excitement and serious discussion that book, The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up, would go on to inspire – and the global fame it would bring its author, Marie Kondo. It would stay on The New York Times bestseller list for 150 weeks, has since been translated into 44 languages, and sold more than 14 million copies (in the same sales ballpark as Douglas Adams’s The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy and Nelson Mandela’s Long Walk to Freedom).

When the book came out in the US and UK, Kondo was already a star in her native Japan, where it had been published in 2011. Today, at 40, she remains the undisputed queen of organising, with a rack of best-selling books, a successful reality TV-Netflix series, hundreds of consultants trained in her KonMari Method, and a net worth estimated at $8m under her belt. To “kondo” has even become a verb.

So what is behind the runaway success of Kondo’s bestselling book? Subtitled The Japanese Art of Decluttering and Organising, it is in itself a thing of beauty: tastefully designed, with spacious text and no illustrations. It neatly distills Kondo’s unique ideas and experiences of tidying – something she had been “enchanted” with since she was aged five. By her own admission, she is a “crazy tidying fanatic”, and “dedicated to tidying and to explaining how to tidy to a very extreme degree”.

KonMari Method

KonMari MethodKondo is a big believer in using her life story to sell her philosophy. She relates how, having read The Art of Discarding by Nagisa Tatsumi, a bestseller in Japan, she began throwing things away – and it was seeing this transformation that led to her cardinal rule: tidying must be done as a “special event”, just once and to perfection. “If you tidy in one go, rather than little by little, you can dramatically change your mindset,” she writes.

The KonMari method preaches that a tidy space is a tidy mind, an idea that’s backed up by scientific studies. Libby Sander, assistant professor of Organisational Behaviour, Bond University, writes, “Research shows that disorganisation and clutter have a cumulative effect on our brains. Our brains like order, and constant visual reminders of disorganisation drain our cognitive resources, reducing our ability to focus.” The tidying effect extends to sleep: those sleeping in cluttered bedrooms are more likely to have sleep problems, including difficulty falling asleep and being disturbed during the night.

“Tidying by category” is another rule, to be done in strict order of clothes, books, papers, miscellaneous items and sentimental items. She used to advise heaping all your clothes in a pile, but now allows subcategories (eg, jackets, trousers, etc). Her tone is firm but light and playful: making tidying fun is half the battle. She never tires of relating the dramatic event that birthed her “spark joy” rule. It resulted from a tidying session so intense that it made her faint. Coming to, she heard a voice say “look at the items carefully and closely”. Instead of looking for reasons to discard an item, you should find reasons to keep them, she realised. “Deciding what to keep on the basis of what sparks joy in your heart,” she writes, “is the most important step in tidying.”

‘Organiser-in-chief‘

With her profile building rapidly, in 2015, Kondo was announced one of Time’s 100 Most Influential People, and “Organiser in chief”, with actress Jamie Lee Curtis praising this “modern-day Marie Poppins”, and recommending the book “for anyone who struggles with the material excess of living in a privileged society”. Elle said the book had “inspired a movement, with folks tossing out half of their possessions in search of enlightenment”.

In fact, the idea of writing a book was not Kondo’s but someone on a long waiting-list for her tidying expertise. With no writing experience, in early 2010, at 24, she joined a publishing training course. It ran a book proposal contest, and Kondo won first prize. One of the contest judges, Tomohiro Takahashi, was so impressed, he bid for and won her first book (and has been her editor ever since). He has said he felt sure she would be famous, and he “felt a mysterious energy around her that I had never experienced around other people”.

That energy is evident on a video call with the BBC. Kondo is smiling, polite, eager to understand and respond to questions, speaking fast in Japanese, translated into English by her interpreter. Her home is neat, minimally furnished with a white curtain and a few long-leaved plants. She wears an ivory jumper, her glossy hair is neatly bobbed and as always she uses her hands expressively.

Alamy

AlamyFifteen years on, what does she feel about the impact The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up has had? “The level of success [it had] blew my mind… I had always believed in the power and strength of tidying,” she says, “but when my book became such an international sensation, of course I was very shocked, and surprised that my ideas would resonate with so many people on such a large scale.”

She has received up to 1,000 emails a day in the past with readers’ photos of homes they have “kondoed”. It’s gratifying, she says, and the change is permanent: “My clients never go back to the mess, because they have been transformed into an organised person.” It also includes cases where “someone has come to realise, ‘wow, this is a relationship that means a lot to me, and I want to dedicate more time to it'”.

On her website she writes about tuning into the “energy” of things; when you feel a “tingle” or a “ching” (a noise she makes), that means you can keep an item. Or she is following rituals, such as tapping a tuning fork on a crystal, and waving it around her head to absorb its “sonic vibrations [that] have a subtle healing power that helps me to reset”.

These seemingly “magic” methods relate back to her time as a shrine maiden, from the age of 18 to 22, at a Shinto temple in Japan, she says. The Shinto religion is concerned with the energy or divine spirit of things, and the right way to live; and a shrine maiden (or miko) is a young priestess who performs tasks such as ritual cleansing of the temple, and performing the sacred Kagura dance.

“There are three pillars of KonMari I can link back to being a shrine maiden,” she says. “First is purifying things – a shrine must be kept pure, which is similar to tidying up. Second is gratitude – at a shrine you give thanks for what you have been given.” She thanks a space before working on it, and suggests giving gratitude to objects, be it a computer, or your shoes. “The third pillar is reflection; being at a shrine gives you space to breathe and listen to your thoughts.”

Marie Kondo’s five culture shifters

Akihiro Miwa’s Style Encyclopedia

I read this book when I was 20. It pictured a room decorated with great imagination: a tatami floor covered with fabric like a carpet, a record player and cabinet painted pink and decorated with ribbons. It was wonderful – hard to believe it was a tiny Japanese-style room. Miwa wrote that there was no need to move or spend a lot of money to live in a beautiful, stylish home; you could remake your space with your own wisdom and ingenuity. Those words encouraged me many times when I was about to give up on my ideal home.

Shinto shrines

I served as a shrine maiden in a shrine in Tokyo from the age of 18 to 22. My work was to help clean the shrine and to grant omamori (Japanese amulets) to the worshippers and visitors. I believe my time at the shrine taught me the importance of purifying a space, and the value of showing gratitude.

The Art of Discarding by Nagisa Tatsumi

This book, published in 2000, and a large number of other Japanese books and magazine features on tidying up that I read in Japan, from my girlhood to my 20s, made a big impact on me.

British antique writing desk

I have loved British antiques ever since I can remember. I acquired my first piece when I was a university student, a writing desk purchased at an antique shop in the Kichijoji neighbourhood of Tokyo. I loved its compact size, glossy wood, and corrugated carving. It was through experiencing the beauty and handmade warmth of time-honoured pieces like these that I developed a sensitivity to feeling joy from objects.

Japanese otaku culture

My older brother was an otaku, an enthusiast of manga (Japanese comics or graphic novels), animé (Japanese hand-drawn and computer-generated animation), and video games. I admired the way he could immerse himself wholeheartedly in something he loved. Perhaps my pride in being a tidying otaku stems from my respect for Japanese otaku culture.

The rituals and mantras are integral to the book’s success, says Mindy Godding, a tidying expert of 20 years and president of NAPO (the National Association of Productivity and Organising Professionals). “I think people found them very soothing, like a balm,” she tells the BBC. “For someone overwhelmed by chaos and clutter, the essence of calm and serenity Marie Kondo portrays – and her simple routines – can be intoxicating.”

That success rests on results, however, like the thousands of “before” and “after” tidying pictures and videos of excess and mess transformed into havens of tranquility. Her reality TV series, Tidying Up With Marie Kondo, showcased those transformations, in which Kondo’s petite (4ft 8in) figure at the start of the episode was invariably overshadowed by mountains of mess, clothes and objects. She soon brought order to the chaos. Her secret weapon, said a review of the Netflix series, was she: “dispenses benedictions and prescriptions, not judgment” and “there are no real heroes or villains. Just an awareness of a consumer culture run amok”.

Launched on 1 January 2019, the Netflix series ramped up Kondo’s global reach – and influence. Charity shops in the UK and US reported spikes in donations; and stores had record-breaking sales of storage items, as customers rushed to join the tidying movement. “The popularity of Marie Kondo showcasing how best to ‘declutter’ your home has had a huge influence on our customers,” said a spokesperson for UK department store John Lewis.

Tidying got political in September 2023, when Kondo joined the likes of Bill Gates and Al Gore at Climate Forward. Invited to discuss “Can a tidy house save the world?”, and share her thoughts about over-consumption and excess, she recapped her life message: pause to buy only things you love and need. When she was criticised for adding to the mountain of rubbish by selling products through her website, she replied: “Certain items do provide us happiness and can energise us. I truly believe in the energy items can provide.”

How does she feel about being called the “tidying guru who transformed modern minimalism”? She pauses: “I’m not sure I can take any credit [for that], it’s humbling you even draw a link. I think while each movement has its own ideology, there are shared ideas and goals… the fact people are taking steps in that direction is wonderful.”

In truth, tidying is big business, with the home organisation industry valued at $15.2bn in 2023, and expected to grow at a rate of 4.7% between 2024 and 2031.

Her legacy, she says, is in the army of of KonMari consultants she has trained – now 900 plus across more than 60 countries. She is currently writing a book on Japanese culture today. “My philosophy and methods are deeply influenced by Japanese history and culture, and writing it will be an exercise for me in exploring and understanding those links.”

Kondo is married to Takumi Kawahara, CEO of her company, and the couple has three children. Since the birth of their third child, a son, in 2021, she has had less time for tidying. She recently told Sky News: “I’m not perfect, I never was,” and admitted to The Telegraph: “My home is messy now I have children.”

“It dawned on me I didn’t have the same time to tidy up perfectly as I used to – you can’t always maintain the perfect space at any given moment,” she says. But she had found truth in the aphorism that your children teach you how to live: “I asked myself, ‘What does spark joy in my life?’, and my answer was right in front of me.”