Accepting the coveted Caldecott medal in 1964, an annual award honouring the “most distinguished American picture book for children”, the author Maurice Sendak addressed the rumbles of disapproval his winning book had received from some quarters about it being too frightening by wryly commenting, “Where the Wild Things Are was not meant to please everybody – only children.”

Of course, far from only appealing to children, after initially sending shockwaves around the literary establishment, over the decades the book has beguiled almost everyone who has encountered it, young and old, from world leaders to film directors. It has inspired films, songs, books, an opera and even a spoof on The Simpsons. For this poll, children’s authors and experts from Singapore and Iceland to Portugal and Peru voted for it in their droves, with one respondent, Pam Dix, chair of the UK section of the International Board on Books for Young People (IBBY), calling it “a perfect, multi-layered picture book that reveals new dimensions on each reading”. Most importantly though, it has indeed captivated generations of children thirsty for mischief, mastery and a cracking wild rumpus.

Read more about BBC Culture’s 100 greatest children’s books:

The 100 greatest children’s books

The 20 greatest children’s books

The 21st Century’s greatest children’s books

Who voted?

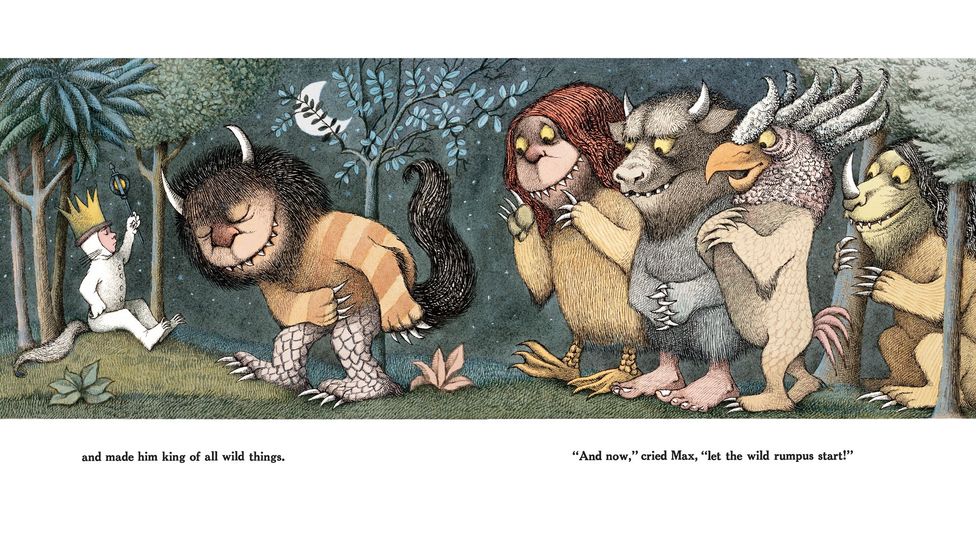

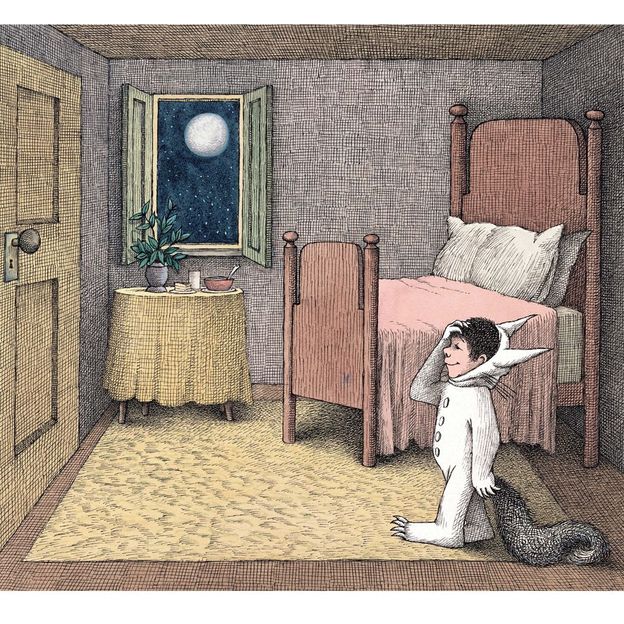

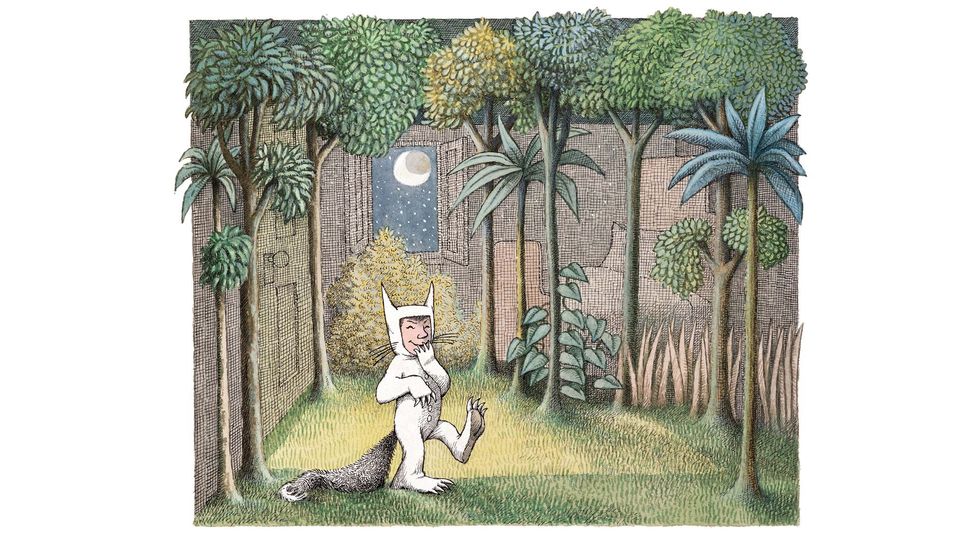

Where the Wild Things Are turns 60 this November. Yet, with its unforgettable colour palette of pinks, blues and greens and its depiction of perennial childhood joys like tree swinging and piggyback rides, it looks as fresh as the day it was born. The story of a loveable rascal called Max whose mother sends him to his room for causing mayhem, it takes a more mysterious turn when, left alone, Max conjures a vivid world of towering trees and vines and sails off to become king of an island of party-loving monsters, before getting lonely and returning home.

(Credit: Where the Wild Things Are copyright © 1963, renewed 1991, by Maurice Sendak)

The son of Polish Jewish immigrants who arrived in the US before World War One, Sendak was born in Brooklyn in 1928. He was obsessed with storytelling from a young age, partly thanks to the wildly imaginative tales his father recounted to entertain him and his older siblings, Natalie and Jack. He was passionate about the cinema, especially Disney films, and an avid reader. When ill health left him confined for long periods at home as a child, he developed strong attachments to particular books, toys and objects in his room, and constantly drew pictures.

Sendak struggled with anxious feelings from a young age. “Children are extraordinarily vulnerable and have few defences,” he told Muriel Harris in a 1970 interview for the journal Elementary English. “Childhood suffering is intense.” He even found the way his mother expressed her affection for him alarming: she played odd games and would jump out and scare him, shouting “whoot!”. He was also fearful of dying: “I think a lot of children are afraid of death,” he told Saul Braun of The New York Times in 1970. “But I was afraid because I heard it around me. I was very ill; I had scarlet fever… my parents were afraid I wouldn’t survive.”

How it really feels to be a child

As Sendak grew into adulthood, he retained a direct connection to those intense childhood emotions. He developed wide cultural tastes, adoring the work of William Blake, Herman Melville and Emily Dickinson, illustrators like Randolph Caldecott, and classical composers including Mozart, Wagner and Beethoven. When he created Wild Things in his 30s, he dug deep into his inner world of childhood feelings and worries, fusing them with the cultural influences he’d absorbed, to conceive the impassioned young Max. It’s a book that captures “this inescapable fact of childhood,” as Sendak described to Braun – “the awful vulnerability of children and their struggle to make themselves king of all wild things”.

Furious at being ordered to his room, Max delves into fantasy, a place where he can vent his emotions about his mother towards a band of imaginary beasts, send them off to bed without ,” he told Nat Hentoff in a 1966 profile for The New Yorker.

(Credit: Where the Wild Things Are copyright © 1963, renewed 1991, by Maurice Sendak)

Picture books exploring emotions are big business today, with titles from Ruby’s Worry to A Shelter for Sadness encouraging children to both express, and try to understand, the full range of their feelings. This was not the case in the early 1960s. Many books had an instructional feel, a sense of being designed to help mould how children behave and develop. As Hentoff said in the New Yorker piece: “Far too many contemporary picture books for the young are still populated by children who eat everything on their plates, go dutifully to bed at the proper hour, and learn all sorts of useful facts or moral lessons by the time the book comes to an end… Any fantasy that may be encountered either corresponds to the fulfilment of adult wishes or is carefully curbed lest it frighten the child…”

Against this backdrop, Wild Things, with its rejection of any notion that children should always be quiet and obedient, went off like a firecracker. Library copies were worn out, children wrote to Sendak in their droves, often sending him pictures of their own wild things which, he said, were sometimes far more terrifying than his own drawings. While he had his detractors, many cultural commentators credited him with revolutionising children’s literature. Sendak’s close friend and editor Ursula Nordstrom, herself a key figure in the development of children’s literature, described the book as being of singular historical importance because, as she told The New Yorker, “[it] is the first American picture book for children to recognise that children have powerful emotions…”. Here, finally, was a book in which children truly saw their beautifully messy and complicated selves reflected back.

But does this still hold true today? Responding to BBC Culture’s poll, Raquel Mestre, a literary agent and editorial consultant for children in Portugal, says that Wild Things is “still a current favourite with the young generations… after all, who wouldn’t identify with this boy, this island, his travels?” Contemporary children might seemingly have more emotional freedom than previous generations, thanks partly to the fashion for child-centred parenting advocated by many experts – currently booming on social media – which calls for more tolerance and gentleness in the face of trickiness and tantrums. Yet in some ways, many children seem more hemmed in than ever, given fewer opportunities to go wild or engage their minds in the creation of fantasy worlds. Statistics confirm that children are playing outside much less than in previous eras, with many plugged into devices inside for hours on end. Sendak’s book is a powerful reminder that wild play and self-expression have an essential role in the development of a child’s imagination. And while the luscious green world that Max enjoys hurtling through with the monsters may be a figment of his imagination, it surely encourages many children to get out and climb real trees.

(Credit: Where the Wild Things Are copyright © 1963, renewed 1991, by Maurice Sendak)

The book has also endured because while its details are delightfully specific – the look of the outlandish monsters, the white wolf suit, the fact Max chases the dog with a fork, and his cry “I’ll eat you up!” in response to being called “wild thing!” – it’s also entirely relatable and open to interpretation. I was obsessed with Where the Wild Things Are as a child and have carried my dog-eared copy, with its 90p price label, through countless house moves into adulthood, a talisman of sorts. My parents divorced when I was a baby and, as a very small child, I found leaving my mum and my regular home to stay at my dad and stepmum’s house unsettling, despite the warm welcome. Looking back, I realise I idolised Max, his ability to sail off into the night, far from his mother, and fearlessly confront those monsters. I longed to be brave just like him.

Of course, Max didn’t actually sail off into the night. But to my child self, there was no difference between what was real and what Max imagined within the book. Interviews with Sendak frequently reference the “doorways” or “secret entrances and exits” between the parallel realms of reality and fantasy that he intuitively understood and could readily slip between, just like a child, when creating. In 1970, when Braun visited Sendak at his home on West Ninth Street in Manhattan, the journalist described the actual passageway to his home studio as “long and narrow and dimly lit”, a space Sendak transitioned through every day to “recover the world of his childhood”. Perhaps this is what Sendak also offers his readers: more than just a book, Wild Things is a portal to the feelings and desires of our own infancy. It actually takes us through one of Sendak’s mysterious passageways, allowing us to not just hear about, but also to re-experience the childhood realm.

Above all, in our age of iPhones, computer games and AI, of oversaturation from the endless churn of 24-hour TV and social media, Wild Things is a much-needed reminder of what really makes children – and people generally – tick: freedom to express themselves, play, connection to nature, family and, of course, love. His masterpiece might be only a few hundred words in length, but it captures the very essence of the human condition: that, when all is said and done, when we need to rest from our adventuring, we all long to go home to where someone loves us best of all.

Read more about BBC Culture’s 100 greatest children’s books:

The 100 greatest children’s books

The 20 greatest children’s books

The 21st Century’s greatest children’s books

Who voted?