Espionage has a split personality in British culture. On the one hand, it’s seen as a glamorous, adventurous spectacle, a vision emerging largely from author Ian Fleming and his most famous creation, James Bond, who first appeared in the 1953 novel Casino Royale. On the other, it is something far less alluring; a grittier yet bureaucratic world found in novels by the likes of Graham Greene and Len Deighton, films like Anthony Asquith’s Orders to Kill (1958), and television series such as James Mitchell’s Callan (1967-72) and Ian Mackintosh’s The Sandbaggers (1978-80).

More like this:

– The rebel spy who’s the anti-James Bond

– The best books of the year so far

– The world’s most unlikely secret agent

One British author tilted the image of espionage in this moodier direction more than any other. British writer John Le Carré arguably had as much impact on the perception of spying as Fleming, but w ith a depiction of it that was quieter and closer to the bone. While Le Carré did this over an astonishing 50-year career and more than two dozen novels, it’s his third novel The Spy Who Came in from the Cold that cemented this vision effectively, resulting in one of the great examples of post-war British fiction, spy or otherwise. Sixty years on from its publication in September 1963, the novel still retains its power.

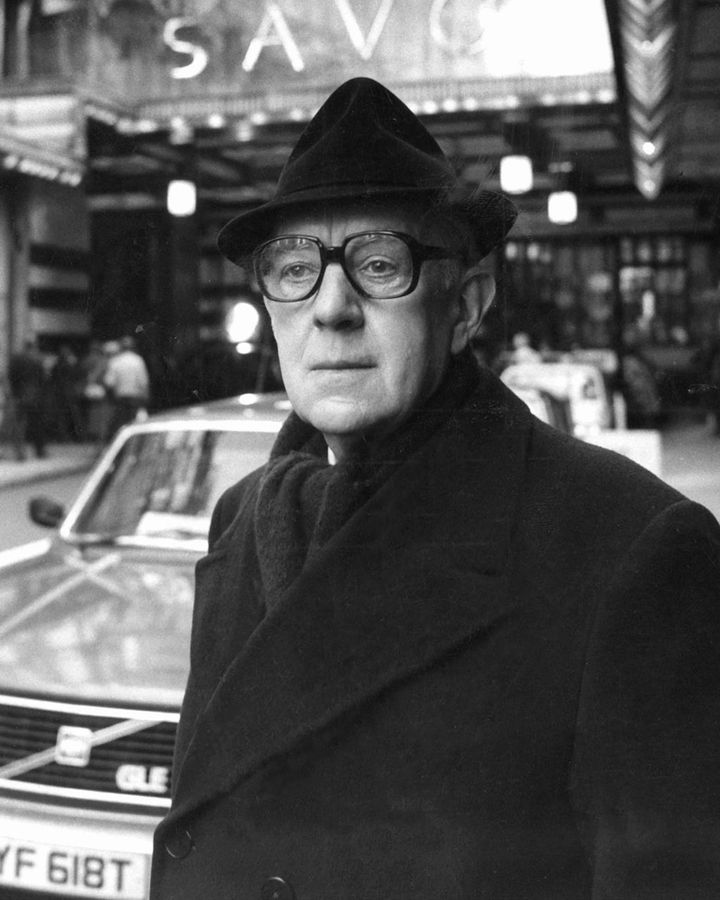

John le Carré in the mid-1960s, by which point he had given up his career in real-life espionage and become a writer full-time (Credit: Getty Images)

Set against the backdrop of a divided, post-war Berlin, the novel tells the story of disillusioned British agent Alec Leamas. Leamas has failed in his mission as head of the West Berlin office of the British Secret Service, and after witnessing the murder of his last undercover operative, Riemick, as he tries to cross the border, he returns to Britain, and requests leave. However, the mysterious Control, the head of “The Circus” – Le Carré’s fictional nickname for MI6, based on its offices’ setting in London’s Cambridge Circus – offers him one last mission before retirement.

Leamas is to purportedly defect to East Germany in order to sow disinformation regarding enemy party member Hans-Dieter Mundt, the man responsible for Riemick’s murder. But, as with all espionage, nothing is what it seems, and, as the mission becomes complicated by Leamas’ cover story, namely his relationship with British Communist Party secretary Liz Gold, tension mounts as to whether he will complete it – or if he is really even meant to.

Amidst the ideological battleground of the Cold War, The Spy transcended the conventional espionage thriller, revealing the raw, gritty reality of field operations undertaken during the period of the Berlin Wall, Checkpoint Charlie and smuggled microdots. However, Le Carré was less interested in merely dramatising the various nuts and bolts of basic tradecraft – though he certainly did so in more detail than any other writer at the time – and was more concerned with questioning the very act of spying itself, emphasising the amoral techniques used in the invisible battle between East and West intelligence services.

How it manages to be so authentic

Le Carré’s background as a real-life intelligence worker could be felt in the authenticity of his work, especially The Spy, as well as in its decidedly pessimistic tone. Born David Cornwell, Le Carré served in British intelligence from the late 1940s, when, for his National Service, he was stationed in the Austrian city of Graz; with his expertise in German, he helped to interrogate defectors from East Germany.

He then returned to study at Oxford, where he became an informer for MI5 on Communist student groups, before joining the agency full time when he left. And it was when working in the dirty world of phone-tapping and break-ins that he began writing – under a pseudonym, as was a service requirement.

He transferred to MI6 in 1960 and became attached to the embassy in Bonn. The Spy was the last novel he published before he was, like many, compromised by double agent Kim Philby’s infamous 1963 betrayal of his fellow British secret service officers. Philby revealed their covers to the KGB, ending le Carré’s intelligence career for good.

However, even without Philby breaking his cover, the chances are that Le Carré would have been found out anyway. Reviewers of The Spy, in particular those from the other side of the Iron Curtain, had cottoned on that the author was likely a genuine intelligence worker. Le Carré, in typical troublemaker fashion, had copies of the book smuggled to countries in the Eastern Bloc, being curious as to how it would be received. Their largely favourable reviews made him a little uneasy, while some saw the obvious reality behind the fiction. Russian critic V Voinov was the earliest to suggest in his review of The Spy for the Moscow-based arts paper Literaturnaya Gazeta that its accuracy could only have been achieved by someone with a history inside the intelligence world.

Richard Burton and Claire Bloom in the 1965 film adaptation of The Spy Who Came in from the Cold, which stood in contrast to the James Bond films (Credit: Alamy)

Of course, the almost mundane level of detail in the book meant those after more Bond-ish spectacles may have been left wanting. The Times review of the period, for example, bemoaned that there was “too much description and not enough action”. Most reviews, however, were positive and even the previous sage of espionage fiction Graham Greene admitted it was “the best spy story I have ever read”.

The firsthand knowledge, grim atmosphere, and complex morality all lent the novel an air of realism, making it stand apart from the imaginative exploits of other spy fiction. It was truly a turning point for the genre, building on groundwork laid by Deighton and Greene novels such as The Ipcress File (1962) and Our Man in Havana (1958), but pushing the boundaries with regards to the credibility of its narrative and melancholy of its tone.

Why it’s really about loneliness

Equally refreshing is the fact that le Carré’s protagonists are not the dashing heroes of typical spy narratives; instead, they grapple with ethical dilemmas, are haunted by personal sacrifices, and left run down and poverty-stricken by the relentless psychological toll of their work. Leamas is genuinely one of British fiction’s most hopeless and pessimistic characters.

This is best evidenced by the fact that Richard Burton was cast as the character in Martin Ritt’s 1965 film adaptation of the book. Whereas the concurrent 007 on screen was smooth, panther-like Sean Connery, in his early 30s, Leamas was middle-aged, with the toll his work had taken written on Burton’s worn face, the result of the actor’s hell-raising lifestyle and drinking. Indeed, the choice of Burton proved a stroke of brilliance in the casting.

“The story of The Spy was really a story of loneliness…” Le Carré suggested in a 1974 interview. Through the stark narrative, readers are exposed to the duplicitous nature of Cold War power struggles, where allegiances shift, and trust is a rare commodity. For Le Carré, loneliness and spying go hand in hand, simply because no one can be trusted.

The Spy was Le Carré’s third novel after Call for the Dead (1961) and A Murder of Quality (1962). Both of those books preceding it were an unusual mixture of spy novel and crime thriller, though leant more toward the latter than the former, in spite of introducing one of fiction’s most popular and enigmatic spooks, George Smiley. He is undoubtedly Le Carré’s most popular character, due to the Karla trilogy of novels: Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy (1974), The Honourable Schoolboy (1977) and Smiley’s People (1979).

The character also conjures visions of actor Alec Guinness thanks to two celebrated BBC adaptations in 1979 and 1982. Though The Spy is still essentially a Smiley novel, his presence is that of a ghostly ringmaster, seen and mentioned only a handful of times. Whereas Le Carré’s Smiley-heavy novels show the narratives more explicitly from his perspective, The Spy more accurately reflects Smiley’s place in wider society; unseen, quietly manipulative, playing long games behind the scenes that no one individual pawn can understand.

“The novel’s merit, then – or its offence, depending where you stood – was not that it was authentic, but that it was credible,” said le Carré. His endeavour to play it straight did not endear him to his MI6 peers any more than to the enemy. In his 2016 memoir The Pigeon Tunnel, he recalled one dinner party, only a few years after The Spy’s publication, during which a former colleague cornered him and gave him a piece of his mind: “‘You bastard, Cornwell,’ a middle-aged MI6 officer, once my colleague, yells down the room at me as a bunch of Washington insiders gather for a diplomatic reception hosted by the British Ambassador,” he wrote. “‘You utter bastard.’ He wasn’t expecting to meet me, but now he has done he’s glad of the opportunity to tell me what he thinks of me for insulting the honour of the Service…”. The mirror le Carré held up to the service may have made former colleagues wince, but it certainly made for great fiction.

Alec Guinness as le Carré’s most famous spy George Smiley; Smiley makes only a shadowy appearance in The Spy Who Came in from the Cold (Credit: Alamy)

Yet, underneath the brutally accurate portrayal of what spying involved, The Spy is really a novel about a lasting, even defiant humanism in the face of battling ideologies, all told through pitch-perfect characterisation. It’s the whole point of le Carré’s work in the Cold War period: no one comes out clean from espionage work, even those who defy their Whitehall, Washington or Kremlin overlords when their conscience finally begins to itch. It’s the likely reality that so annoyed his former colleagues, and the novel is all the better for unflinchingly addressing questions around the ethics of espionage.

As The Spy celebrates its 60th anniversary, it resonates as powerfully today as it did in the midst of the Cold War, especially as old divisions reappear and global crises follow one after another. The novel’s credibility is key to the enduring power of le Carré’s storytelling, even if its overall truth is an uncomfortable one to accept. As he wrote in the book, “Intelligence work has one moral law – it is justified by results”. What really is the price of public safety? Le Carré was too great and mature a writer to offer up any easy or comforting answers.