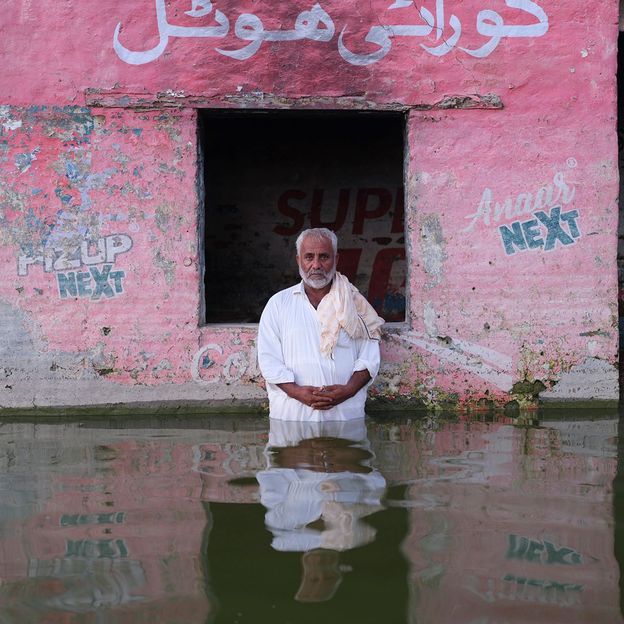

Muhammad Chuttal, Khaipur Nathan Shah, Sindh Province, Pakistan, October 2022, from the series Drowning World (Credit: Gideon Mendel)

The people in Gideon Mendel’s portraits stare back at us, not quite defiant. They appear serene, composed – and in many cases, submerged in the water that has flooded their homes. “The gaze, where people engage with the camera, is the visual focus, the emotional centre of each of these images,” Mendel tells BBC Culture. “A lot of people have asked me: ‘What are people saying, what is the gaze?’ And I think it’s strangely enigmatic. It’s not necessarily accusing. I don’t think it’s saying: ‘Look, this is your responsibility’. I think that it’s saying, ‘Take a look at what’s happened to me’. And it’s inviting us to witness their lives at this moment.”

Joy Christian, Dorca Executive Apartments Otuoke, Ogbia Municipality Bayelsa State, Nigeria, November 2022, from the series Drowning World (Credit: Gideon Mendel)

The South African photographer started work on his Drowning World and Burning World series in 2007, after images he’d taken that year of flood victims in India and the UK were published side by side. “It was the first sense I got of a way we could establish a global conversation,” he says. “I realised that the people I’d photographed in the UK and the people I’d photographed in India, although their circumstances were so different in terms of wealth and poverty and social support and help they might get after a flood, they had a kind of shared vulnerability – being in the water united them. What I did with that series which I called Submerged Portraits was almost establish a typology, a way I’d photograph different kinds of people.”

João Pereira de Araújo, Taquari District, Rio Branco, Brazil, March 2015, from the series Drowning World (Credit: Gideon Mendel)

Mendel’s work – currently showing at the Soho Photography Quarter in London – is focused on the aftermath of flooding or wildfires. “It seems counterintuitive to be making a portrait in that context, but actually it’s something which my subjects say felt like the right thing, it felt like the natural, obvious thing to do. It’s not as if this is a moment when people are fleeing. I’m not asking people who are running away from the onrush of water to stop. I’m going back to flooded communities.”

Shirley Armitage, Moorland Village, Somerset, UK, February 2014, from the series Drowning World (Credit: Gideon Mendel)

Capturing his images is an intensely moving process. “I followed Shirley into her home, which was flooded, and she was very shocked because when she’d left initially, the water had been at ankle height, and when we returned it was at chest height. Having followed her into that environment, I’m always somehow connected to her.”

Rhonda Rossbach, Derek Briem and Autumn Briem, Killiney Beach, British Columbia, Canada, 16 October 2021, from the series Burning World (Credit: Gideon Mendel)

The portraits can echo photos of homeowners proudly posing next to their properties – a resemblance that Mendel acknowledges. “When making my video pieces, I often film people moving through their homes, through their properties and I don’t direct them, I just see what happens, but filming people going through their burnt houses, what a lot of people instinctively do is give me the house tour – ‘This is the bathroom.’ Or they’ll say: ‘Well that was the bathroom, if you look three stories up you can see the remains’. People try to figure out what was where in their homes, yet it’s very much the house-proud home tour.”

Jenni Bruce, Upper Brogo, New South Wales, Australia, 15 January 2020, from the series Burning World (Credit: Gideon Mendel)

Mendel is keen to show his subjects on the same level as the viewer. “What’s very important to me in the portraiture is that people don’t come across as victims – that they have agency, that they are showing us what’s happened to them but not as victims.”

Florence Abraham, Igbogene, Bayelsa State, Nigeria, November 2012, from the series Drowning World (Credit: Gideon Mendel)

“I was photographing in Nigeria in 2012,” says Mendel. “Florence Abraham showed me her business and home. She was a baker, and she had a whole bakery – she said she employed 24 people. And then a lot of people made a living from taking her bread on bicycles and distributing it – so there were a lot of people economically dependent on her and it was all destroyed. The flour, mixing machines and bread ovens – it was all completely destroyed by the flood, in a situation where there’s no culture of insurance, or of state compensation or anything, so she’d basically just lost everything.

“At the end of photographing Florence, I tried to give her compensation for her time. She responded in a way which has just really impacted me ever since – she said to me, ‘I’m sorry, I don’t want to be rude, but I don’t want your money. I just want you to show the world what’s happened.’ And that just really resonated. And I know I’m not an NGO, I have no power to really help people in any physical way. But what I can offer people is a kind of deep witnessing of what’s happened to them.”

Gurjeet Dhanoa, Rock Creek, Superior, Colorado, USA March 2022, from the series Burning World (Credit: Gideon Mendel)

“It’s now 16 years since I began doing the work and it’s been a journey for me – when I began, I was much more of a traditional photojournalist,” he says. “My approach to photography has become in a way more conceptual, and I feel like I’m more influenced by contemporary art than contemporary journalism in the way that I work. I’m not sure if I’ve evicted myself or whether I’ve been evicted from photojournalism. It’s a very different kind of way of working, although I do use all of those skills.”

Amjad Ali Laghari, Goth Bawal Khan village, Sindh Province, Pakistan, September 2022, from the series Drowning World (Credit: Gideon Mendel)

Camera technology has also evolved since Mendel began his project. “For the first years of working in flooding, I was working in an analogue way, I was on old Rolleiflex cameras, which was both beautiful and crazy, working in the most difficult circumstances you can imagine with these old cameras which would jam – after many failures in that area, I did eventually move across to working with digital cameras. But what I really miss about the analogue period is less the technical side, it’s more the theatre. And I think the people I was photographing responded really well to the theatre of working in film.”

Kevin Goss, Greenville, California, USA, October 2021, from the series Burning World (Credit: Gideon Mendel)

As well as a shared vulnerability that connects the subjects of Mendel’s photos with the viewer, there’s a sense of our global vulnerability. “We have a shared landscape,” he says. “I think there’s always the danger that people feel this is something that happens ‘over there’. I was very struck when I photographed the aftermath of the floods in Germany in 2021. A lot of people died, it caused huge damage, and a lot of people said: ‘This doesn’t happen in Germany. This happens in Bangladesh and Africa, this doesn’t happen here’. There is the sense that it’s all going to happen to other people ‘over there’. But the velocity of horrific climate things happening all over the world, in unexpected places, is making us reassess.”

Abdul Ghafoor, Mohd Yousof Naich School, Sindh Province, Pakistan, October 2022, from the series Drowning World (Credit: Gideon Mendel)

“I work in floods where the water tends to sit, where it waits,” says Mendel. “People often think all floods are the same, but the geography of floods in different contexts are very different. I’m from South Africa and the kind of floods you get in South Africa tend to be very sudden and very violent and very dramatic, where the water comes down a river or a creek and pulls cars, it’s tsunami-like. And then there are also floods which you often get, which I’ve photographed in West Africa, in Asia, and often in Europe as well, in America, where the water sits around for a long time – for days, weeks, sometimes even months. When I photographed the floods in Pakistan last year, I was working in places that still had a lot of water six weeks after the floods had arrived.”

Uncle Noel Butler and Trish Butler, Nura Gunyu Indigenous Education Centre, New South Wales, Australia, 28 February 2020, from the series Burning World (Credit: Gideon Mendel)

When Mendel started his project, he was trying to find a way to respond to climate change that might challenge preconceptions. “I spent time looking at photo archives, looking at Flickr, looking at the way climate change was being represented. And it’s not the case now, but at that point, if you were searching for an image of climate change, you’d immediately get 100 pictures of polar bears and glaciers,” he says. “I just felt that was really problematic and it felt so far away and so distant, and I wanted to make images that were visceral, make images that were direct. I wanted climate change and all the impacts of climate change to be looking directly into the eyes of the viewer.”