We live in an age of unprecedented information sharing, where complex social, political and cultural topics can be investigated at the touch of a screen. Yet recent years have sparked a renewed interest in an age-old site of learning: the local museum. This is because many such spaces are taking on an increasingly diverse and imaginative approach to storytelling, offering up a hyperlocal perspective on topics such as immigration, colonialism, class and identity, and capturing the attention of a new generation in the process.

More like this:

– The radical trend millennials love

– Six extraordinary gardens

– Rise of the ‘no-wash’ movement

According to Sophie Smith Sachdeva, founder of Narrative by Design, a company that helps museums present the stories they tell, this is because local narratives offer a means of “tackling really big subjects in a way that’s manageable,” she tells BBC Culture. “If you’re looking at subjects through the lens of places or people from an area you know well, it immediately makes conceptual and complex conversations less abstract and more engaging.”

For Tina Smith, head of exhibitions at District Six Museum in Cape Town – a space dedicated to the memory of a neighbourhood destroyed during South Africa’s Apartheid – local museums can also play an educational role that schools cannot. By offering immersive experiences “that hold up a mirror”, create space for discussion, and forge a link between the past and the present, she tells BBC Culture, hyperlocal storytelling is both “grounding and always relevant”. Moreover, in the midst of fierce debate over what should and shouldn’t be taught in schools in the US, UK and beyond, such museums have the unique freedom and archive material to do so.

The burgeoning success of hyperlocal museums is spawning multiple new spaces dedicated to helping communities understand, and reckon with, their local past – from the forthcoming St Paul’s Museum in Bristol, a decolonised museum “to enrich and involve the local community”, to The National Centre for Research and Remembrance that will occupy the site of the last Magdalene Laundry in Dublin. Here, we look at seven existing museums leading the way in proving that it is histories, plural, not one myopic history that can teach us about the past.

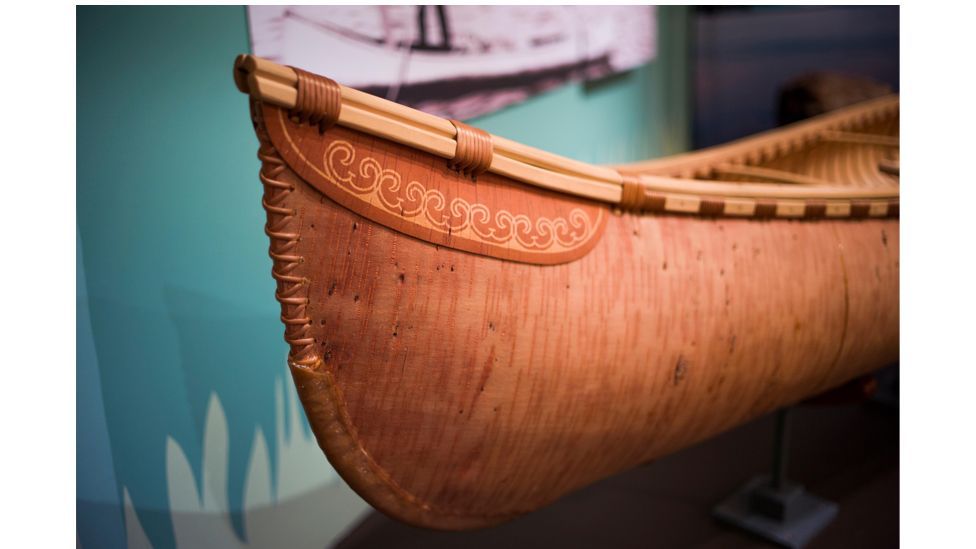

The Abbe Museum in Maine showcases local Native American history and culture (Credit: Alamy)

1. The Abbe Museum, Maine, US

The Abbe Museum in Bar Harbor, Maine, is a longstanding local museum making much-needed changes to its structuring to better reflect and respect the area’s past. It was founded in 1926 by a wealthy collector of Native American artefacts, but began a process of decolonisation in 2015, in collaboration with local tribes. Now, it’s a contemporary two-site Smithsonian Affiliate dedicated to the history and cultures of Maine’s Native people, the Wabanaki. In 2020, the Abbe appointed Chris Newell, a tribal member, as its director, galvanising its mission to work “with the Wabanaki Nations to share their stories… with a broader audience”. It achieves this through a permanent exhibit of archaeological, historic and contemporary objects that shed light on “more than 12,000 years of history, conflict, adaptation, and survival in the Wabanaki homeland”, as well as a roster of temporary shows. The latest of these, Wabanaki Modern, opens in May and will consider the artistic legacy of the “Micmac Indian Craftsmen” of the 1960s, the first modern indigenous artists in Atlantic Canada.

Sydney’s Qtopia is a museum dedicated to the local histories that helped shape LGBTQI+ culture in the region (Credit: Courtesy of Qtopia)

2. Qtopia, Sydney, Australia

Qtopia is Australia’s first dedicated LGBTQI+ museum, and opened earlier this year in two temporary spaces in Darlinghurst, Sydney. “Sydney has one of the largest queer communities in the world,” Qtopia’s CEO Greg Fisher tells BBC Culture, “and it’s very much localised in and around Darlinghurst, especially Oxford Street, where the Mardi Gras parade [an annual World Pride celebration that stemmed from a LGBTQI+ demonstration in 1978] happens.” The museum will open the doors of its permanent site in time for next year’s parade, and its new location – in the former Darlinghurst police station, where many members of the gay community were subjected to incarceration before the legalisation of homosexuality in 1984 – offers what Fisher dubs “a chance to liberate the property and give it back to the community”.

Qtopia has wide-spanning ambitions: it will host an Aids memorial, telling the stories of the Australians who lost their lives to the disease, while a series of rotating exhibitions will examine the pivotal points and hard-won victories in Australia’s queer history from the First Nations to today. Nevertheless, Smith explains, it will remain rooted in its hyperlocal past. For instance, the museum’s recent exhibition recreating Ward 17 South, Australia’s first HIV/Aids unit, located at the neighbouring St Vincent’s Hospital, will be made permanent in the new site. “So many events that shaped Australia’s queer culture happened right here,” he says.

Working-class lives of the 19th and 20th Centuries in Ultrecht’s District C are remembered at the Volksbuurt Museum (Credit: Volksbuurt Museum)

3. Volksbuurt Museum, Utrecht, The Netherlands

The Volksbuurtmuseum, or Dutch Museum for Working-Class Neighbourhoods, is a unique space, dedicated to the everyday life, customs, traditions and struggles of the working-class residents of Utrecht’s District C neighbourhood during the 19th and 20th Centuries. “In the late 1960s, after years of demolition and redevelopment, the residents of District C began actively engaging with their living environment, founding a committee to preserve and restore the neighbourhood,” the museum’s communications coordinator Christel Schatorjé tells BBC Culture. They collected photographs and other relevant materials among themselves, she explains – items that formed the basis of the Volksbuurtmuseum’s expansive yet intimate collection. Today, this serves to paint a vivid picture of the lives of “ordinary people” over the course of a century, fostering a sense of pride and identity in the community they helped shape through guided tours, a programme of events and workshops and a growing archive of oral histories from inhabitants of Utrecht’s working-class neighbourhoods.

A museum and memorial, Greenwood Rising was established in the neighbourhood on the 100th anniversary of the Tulsa Race Massacre (Credit: Alamy)

4. Greenwood Rising, Tulsa, US

In 1921, one of the worst incidents of racial violence in US history occurred in Greenwood, Tulsa. The Tulsa Race Massacre saw armed white mobs set the wealthy black neighbourhood ablaze, killing as many as 300 residents and leaving almost 10,000 others homeless. This act of terrorism was widely relegated to the annals of history until the approach of its 100th anniversary, when Greenwood Rising, a museum-and-memorial, was established at the heart of the North Tulsa neighbourhood.

Composed of multiple interactive spaces that weave a thread back and forwards in time, the museum reveals the spirit of entrepreneurship that underscored the historic district, once dubbed Black Wall Street, prior to the attacks, as well as what its website describes as the centuries-old “political, economic, and social systems of anti-blackness that created the conditions for the massacre”. Later rooms bring the massacre to life through witness accounts, and detail the painstaking process of rebuilding Greenwood and its fluctuations in economic success thereafter. The final space asks visitors to contemplate “restorative justice and contemporary issues of anti-blackness”, striving to actively link past and present, local and national, to highlight the repercussions of systems of oppression at every scale.

The Wimbledon Museum explores the real lives of past residents – from Suffragettes to the early railway workers’ community (Credit: Wimbledon Museum)

5. Wimbledon Museum, London, UK

Wimbledon is today synonymous with its international tennis tournament, but the London suburb has a rich and diverse history that extends far beyond the court. Much of this is linked to the arrival of the railway in 1838, and the emergence of what local historian Matthew Hillier describes to BBC Culture as “a significant permanent railway worker population” to assist in the railway’s ongoing development. What was once a leafy, aristocratic enclave became a bustling commercial town within a matter of decades, in no small part thanks to the railway workers and the community they helped build, literally and metaphorically – a subject examined in a 2019 exhibition curated by Hillier at Wimbledon’s local museum.

“I think one important role of local museums is showing how individuals and communities can make a difference,” Jacqueline Laurence, director of the recently refurbished Wimbledon Museum, tells BBC Culture. “For instance, the railway workers created a club to collect contributions for the families of workers who were injured, or even killed, at work.” (A collection box once sported around the neck of a fundraising dog forms part of the archive). Other parts of the newly refurbished museum’s collection evoke similar tales of collective solidarity, Laurence explains, from records and objects documenting the campaign for Women’s Suffrage in Wimbledon, to the story of how the suburb welcomed Belgian refugees during World War One.

Manhattan’s immigrant stories are remembered in the immersive Tenement Museum on the Lower East Side (Credit: Ryan Lahiff/ Tenement Museum)

6. Tenement Museum, New York, US

New York’s Tenement Museum occupies two preserved tenement buildings located on Orchard Street in the Lower East Side of Manhattan. Inside, historically recreated homes speak to the experiences of the working-class European, Jewish and black migrant and immigrant families who resided there in the 19th and 20th Centuries (an estimated 15,000 people in total, from more than 20 nations). The museum’s mission is to “forge emotional connections between visitors and immigrants past and present, and enhance appreciation for the role immigrants play in shaping the American identity,” its fact sheet explains – work that “has never felt more urgent”. It does so through a selection of themed guided tours within the tenement buildings and the surrounding neighbourhood. “It’s this idea of looking at the stories of people who weren’t considered important in their time,” Kathryn Lloyd, senior director of programmes and interpretation at the museum told Yes Magazine last year, “and really lifting up those stories to see them as essential for understanding US history”.

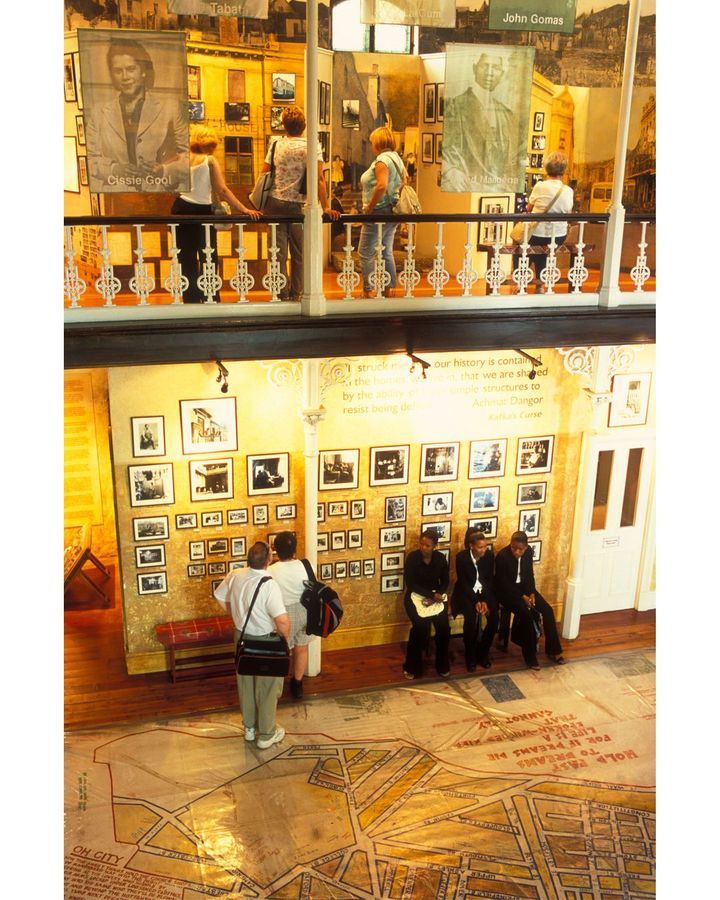

District Six Museum honours the community of locals who were forcibly removed from their neighbourhood during Apartheid (Credit: Alamy)

7. District Six Museum, Cape Town, South Africa

Last but not least, the District Six Museum exists to honour a vibrant community of freed enslaved people, merchants, artisans, labourers and immigrants who were forcibly removed from their Cape Town district to “barren outlying areas” during Apartheid, and their homes destroyed. The museum, which opened in 1994 in a Methodist church within the site of removal, centres on the recollections of the former District Six residents, explains Tina Smith, head of exhibitions. “Our permanent exhibition, Digging Deeper, demands visitors to connect with the District Six residents’ stories using all of their senses. We’re a memory-driven museum, not an object-driven one.”

In the 2000s, the museum expanded to incorporate the District Six Museum Homecoming Centre, where conferences and educational seminars are held, as well as a programme of events. This includes a number of artist collaborations – most recently a celebratory dance production dedicated to Johaar Mosaval, a District-Six-born ballet dancer who went on to become a principal performer with Britain’s Royal Ballet. “We work with people and organisations all over the world,” Smith says, demonstrating the power of a hyperlocal endeavour to resonate on a global scale. “We had no idea we would have this reach; we’ve become a broader platform to rally around basic human rights, around issues of land, of gender, class, identity politics – all of which are still so important and relevant.”