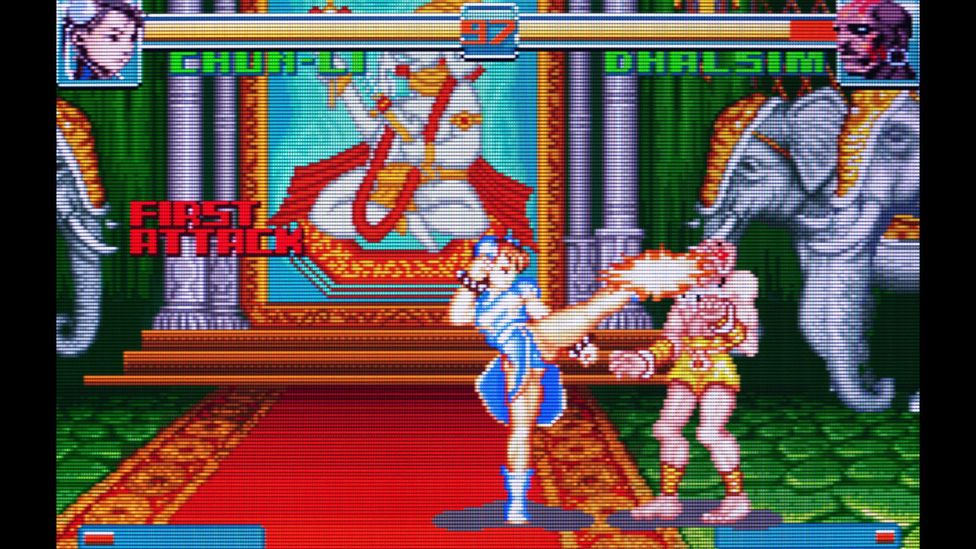

Stepping into a video game arcade in the early 1990s, one particular title pulsed through the neon haze: Street Fighter II (SFII). This competitive fighting game from Osaka-based company Capcom debuted in 1991, and drew throngs to its vibrant visuals, distinctive moves and jet-setting playable characters: brooding warrior Ryu (Japan); his tousled buddy/rival Ken (USA); volatile sumo wrestler E Honda (Japan); electrifying Amazonian man-beast Blanka (Brazil); peppy martial artist and Interpol officer Chun-Li (China); fire-breathing yogi Dhalsim (India); combats-clad pilot Guile (USA); and hulking wrestler Zangief (Russia). Its pulse-quickening soundtrack (composed by Yoko Shimomura) cut through any surrounding clamour, and remains instantly evocative decades later.

More like this:

– Indofuturism in video games

– The music most embedded in our psyches?

– How gaming became a form of meditation

Since its original release, SFII has given rise to copious tie-in merch (spanning collectible figures to clothing and cologne), adaptations and updates. It’s also the subject of a new book, Like a Hurricane: An Unofficial Oral History of Street Fighter II, collated by US videogaming writer Matt Leone. In the foreword, SF series commentator James Chen observes that: “SFII wasn’t just a popular video game. It was a cultural phenomenon unlike anything we’d seen since Pac-Man. While games like Super Mario Bros and The Legend of Zelda had massive fanbases, they were still considered kids’ properties… Adults did not take video games seriously. But SFII appealed to everyone.”

Such mass appeal placed SFII coin-op cabinets across everyday settings: at fast-food outlets, shopping malls, video-rental stores, entertainment centres and more. It proved a formative event for countless players of all backgrounds. Leone tells me about an early 90s Californian summer when he spotted a truck delivering a SFII machine, and chased it on his bike to its destination. Seth Killian, a former gaming tournament competitor/commentator who would later become a Capcom senior manager (and have a SFIV boss character named after him), describes discovering SFII at a “hole-in-the-wall” arcade in suburban Illinois.

SFII included a range of characters, each with their own distinctive fighting styles (Credit: ArcadeImages/ Alamy Stock Photo)

“SFII stood out visually with huge characters and beautiful animations, but what really grabbed me was the crowd around the machine,” says Killian. “Competing against a live opponent, in front of strangers, to see who kept their quarter, and who went to the back of the line? The experience was intoxicating.”

Like a Hurricane charts the creative storm that inspired SFII, as well as industry battles (particularly involving Capcom and rival company SNK), cultural contrasts, pre-internet communication glitches between Capcom’s Japan and US offices, and what sound like toxic working environments (gruelling hours; alleged bullying “banter”). The game’s predecessor, Street Fighter (1987), had limited reach but bold ambitions, which set the stage for SFII’s ground-breaking incarnation.

“If you pit a boxer, for example, against a kickboxer or someone who knows bojutso… you get all these very interesting combinations,” says SF director Takashi Nishiyama, who conceived the first game with planner Hiroshi Matsumoto. “So Matsumoto and I ended up coming up with these ideas together, to give the game deeper story and character elements.”

Character-driven fighting

For SFII, Capcom’s team had shifted (with Nishiyama and Matsumoto departing for SNK), but the game’s characters and range were enriched by the vivid artwork of Akira Yasuda, and a six-button/joystick control design that (perhaps accidentally) allowed players to deliver swift combo attacks. Shimomura’s poppy melodies and effects – including the cries that heralded different characters’ special moves (“Hadouken!”; “Shoryuken!”; “Yoga fire!”; “Sonic boom!”) – also heightened the sense of personality. You grew familiar with these characters, and genuinely rooted for your favourites; SFII established a kind of rapport that arguably hadn’t existed in gaming before.

“It’s rare that a game makes such big strides forward in so many different ways,” says Leone. “And it all fit together so well — you could look at how Capcom loosened up the control input requirements, which blended well with the game’s animation and made players feel like they were more in control, which fed perfectly into the game’s competitive elements, which fed perfectly into how arcade games made money.”

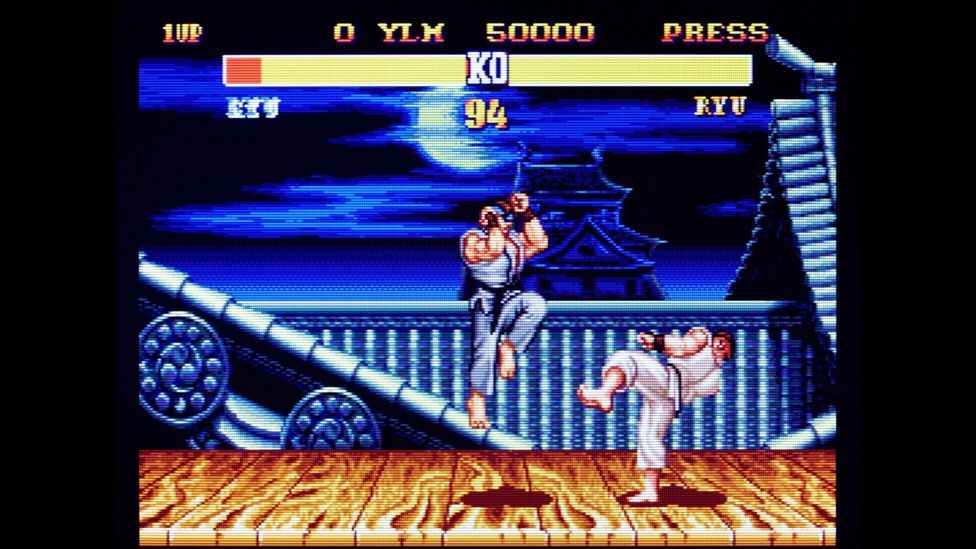

By featuring a two-player mode that requires direct, human-to-human competitive play, SFII gave a boost to the declining video game arcade business (Credit: Alamy Stock Photo)

SFII had players not just competing for high scores, but demonstrating fierceness and flair – against the machine, or each other. It bolstered the “fighting-game community”, through coin-op arcades, via home consoles (SFII made its multimillion-selling debut on the 16-bit SNES in 1992) and into modern digital realms. It invited hardcore gamers and newbies alike.

My intro to SFII was as a schoolgirl visiting the cavernous central London arcade Funland. I was entranced by its sound and style – and thrilled to have the rare option to pick a female fighter. Chun-Li was cool – though her signature moves also exposed her body with a scrutiny that didn’t apply to her male peers. At the time, I partly glossed over uneasy details, even SFII’s weird opening sequence, where a generic blond/blue-eyed fighter knocked out a naked black opponent, in front of jubilant white crowds. Growing up amid the casual misogyny and racism of ’80s/’90s pop culture (where “blackface”, “brownface” and “yellowface” were repeatedly played for fun) might have inured me. I’d never seen anyone Arabic like me onscreen – nor would I in other fighting games of that “golden age”: Mortal Kombat; King of Fighters; Virtua Fighter; Tekken. Strangely, SFII’s main characters seemed both overblown and empathetic; ultimately, I aligned most with the mutant Blanka (whose game narrative also revealed the soppiest ending).

“Certainly, the stereotypical character designs and some of the gender/racial elements are not the best,” says Leone. “There are complex reasons behind those, some related to culture changing over time, but also relating to cultural differences between Japan and other territories, and the specific tendencies of the people who made the games.”

SFII was revised several times over the years, including a Champion Edition in 1994 (Credit: ArcadeImages/ Alamy Stock Photo)

It became increasingly hard to keep apace with SFII’s rapid-fire revisions, often created as Capcom’s counter-responses to rival titles, bootlegs and hardware surplus. The Champion Edition (1992) extended player choice to the four “boss” characters (including a crooked black boxer who looked like US heavyweight Mike Tyson, and was initially named “M Bison”); Street Fighter II Turbo (1992) accelerated the speed; Super Street Fighter II: The New Challengers (1993) added additional fighters. Cheat codes and “secret character” rumours amplified SFII’s mystique, but eventually, it felt like diminishing returns. Arcades were expiring; home gamers were getting kicks from different genres. By SFIII (1997), the series no longer seemed in its prime – although SFVI is scheduled for release this year.

Over time, SFII has sustained a unique cultural reach. Its music is sampled on multi-genre tracks, from a terrible 1994 pop-rap single (which I bought on cassette), to works by Kanye West, the Arctic Monkeys, and Nicki Minaj (whose 2018 single Chun-Li merged empowerment and exotica). Its characters inspired a show-stopping gag in Jackie Chan’s Hong Kong action caper City Hunter (1993) as well as the surreally awful Hollywood blockbuster Street Fighter (1994, starring Jean-Claude Van Damme, Raul Julia and Kylie Minogue). More recently, they’ve been referenced in movies including Wreck-It Ralph (2012) and Shazam (2019) – and when SF characters became playable within Fortnite’s epic Battle Royale (since 2021), it felt like meeting old friends.

SFII has become part of gaming legacy, as well as an economic highlight; by 2017, the game had generated a revenue of $10.61billion. At the National Videogame Museum in Sheffield, SFII is on regular arcade rotation, while its archive features toys, memorabilia and manuals.

“At the heart of SF is the idea of competition, something that is incredibly intrinsic to video games,” says NVM curator Emily Theodore-Marlow. “In SFII, players could choose from a cavalcade of interesting, international characters, many of whom would become larger-than-life cultural figures, endlessly referenced, appearing in cosplay, fan art, film and music… Despite being a 30-year-old franchise, SF remains incredibly important to contemporary games and gamers.”

SFII lingers in the collective psyche, as Killian adds: “SF showed that games could go beyond obsessive solo pursuits and really bring people together. Victory didn’t come from mastering pre-set patterns, it came from deeply understanding another human. The enduring magic of multiplayer set the stage for the nascent internet, and inspired generations of game developers.” It’s a game with seemingly infinite lives – and an emotional punch that connects.