Earlier this year, visitors to the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Kimono Style would have been treated to a stunning example of Japanese craftsmanship. Made in the late 1800s, the Meiji Period, the fisherman’s jacket or . The piece had a particular flourish: the yarns were dyed with small geometric patterns before being used to sew and stitch.

More like this:

– Why ‘wear, wash, repeat’ makes sense

– How to dye clothes at home – naturally

– The stories hidden in an ancient Indian craft

This luxurious adjunct aside, the jacket’s makers would have been astonished at the sight of it hanging on the wall of one of the world’s most prestigious museums. Sashiko emerged through necessity, particularly in poor rural areas, during the Edo period. “Cotton came late to the north of Japan,” explains craft and design writer Katie Treggiden. “So the only way people could get hold of it was as tiny rags of fabrics, that were either passed around or bought from tradesmen from the south. Sashiko – literally, ‘little stabs’ – was a way of connecting all those little pieces into a quilted fabric, known as , that would keep them warm.”

A fisherman’s jacket – or donza – created in the Meji Period is a stunning example of sashiko craftsmanship (Credit: Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Katie Treggiden is among the guest panellists at this year’s Design for Planet Festival, along with Madeleine Michell of British slow-fashion brand Toast, who are keen advocates of clothes repair and visible mending. The festival takes place this year at the Enterprise Centre, University of East Anglia, UK, one of the world’s most sustainable buildings, from 17 to 18 October, and under the theme of Collaborate, it aims to mobilise the UK’s design community to unite efforts in addressing the twin climate and ecological crises. Guests will hear from leading voices in sustainability and design today on topics ranging from food systems to fashion, and next-practice materials (innovative materials) to future mobility needs.

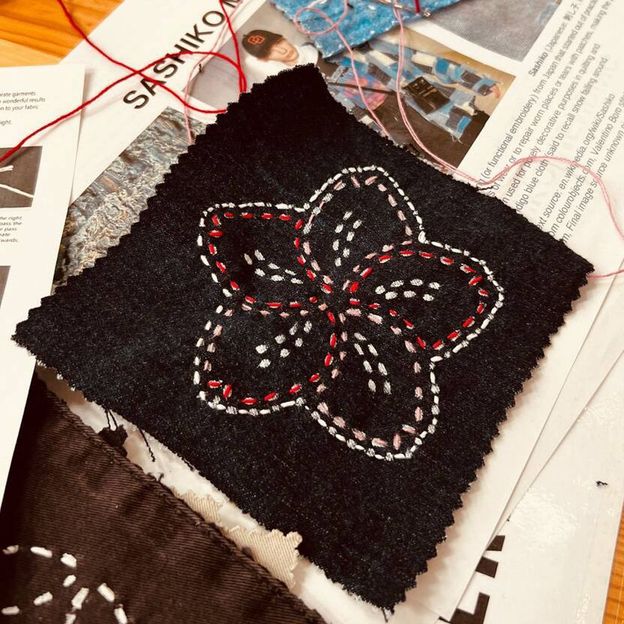

It’s perhaps no surprise that sashiko has become a wider trend in the West – it is simple to do, and beautiful as well as practical. Today, that rich aesthetic of patchwork swatches in a hundred shades of indigo, carefully worked over with white stitches, can be found – like the Met’s – in art galleries, demonstrated in small craft workshops, and across thousands of posts on TikTok and Instagram.

Sashiko tips

– Sashiko thread comes in different weights, bleached or unbleached, and also in red and blue. Use a thread that is slightly thicker than the fabric you are sewing on to.

– Make sure your patching fabric is the same weight or even slightly thinner than the fabric you’re mending. “You don’t want it to rub or to feel stiff,” says Jessica Smulders Cohen.

– Sashiko needles are longer for a reason – so that, if you want, you can do more than one stitch at a time.

London’s V&A and the Hove Museum of Creativity are among the UK venues to offer sashiko workshops recently. Participants in last years’ Great British Sewing Bee were challenged to upcycle denim pieces, using sashiko – Rob Jones of Romor Designs was among those whose sashiko and boro work featured in the semi-final in 2022, and Jones runs workshops in person in London and online. In the US, Atsushi Futatsuya of Upcycle Stiches has been running an in-person sashiko workshop. In the fashion world, luxury Japanese brand Kenzo employs the technique liberally, using it to enliven hoodies and sweatshirts, even on the lining of its Target parka.

Sashiko workshops – including one by Rob Jones of Romor Designs – are increasing in popularity (Credit: Romor)

Why now? “Now, more than ever, there’s a real focus on mending,” says knitwear designer Hannah Porter. “People are becoming more conscious when it comes to caring for their clothes. Sustainability applies to various facets of the clothing industry, from considering the materials, to where your clothing is made and who has made them. Japanese mending is such a beautiful ancient craft and people want to learn these techniques to make their clothing more bespoke and interesting. Sashiko is also very beginner friendly so it’s a great skill to learn within the atmosphere of a workshop, and meet like-minded people.”

It is, agrees Jessica Smulders Cohen, ideal for those who are only just starting their journey into repair; the designer and weaver now runs sashiko courses for slow-fashion brand Toast, and will be running a workshop at the Design for Planet Festival. “It’s the most basic form of stitching,” she smiles. “You can just literally pull it through to the back of the fabric from the front and up again. And, if you create a row and then come back and fill in the gaps, you can create a strong ‘brick wall’ of stitches, making it ideal for denim repair.” But it’s not just denim. “As long as you use appropriate matching thread, you can use sashiko across all woven fabrics. As a technique, it’s very versatile.”

All you need to start is a water-soluble marking pen, or pencil, to draw patterns on the cloth; a pattern to trace; sashiko needles and a sashiko thimble on the middle finger to support the needle in continuing the running stitch for the technique to work. Some menders give a slight twist to the yarn to give it extra strength; others, like Smulders Cohen, may wax the yarn with tailor’s beeswax, to make it stronger. Complete beginners, however, can use two-ply embroidery thread. But it’s not just the simplicity of the technique that appeals. “I like that the patch isn’t the most prominent feature; the stitches are,” says Smulders Cohen.

“And stitching is like handwriting; everyone’s technique is slightly different,” she continues. “As you gain in confidence, you can start trying cross stitches or turn the running stitches into little boxes.” Traditionally, according to Japan Objects website, there are four types of geometric pattern. features straight lines that cross each other.

The V&A is among the venues to have offered sashiko courses recently (Credit: V&A, London)

Playfulness, however, is key, as is making your embroidery your own. Atsushi Futatsuya of Upcycle Stitches is one of a new generation of Japanese practitioners (see video, above). “I know people think there should be rules in sashiko – that the stitch sizes are always equal, the spaces between the stitches have to be a certain percentage of the actual stitches,” he says. “Because of these rules, the stitching tends to be very slow – and there’s a beauty in that. [But] I don’t follow those rules. In the 19th Century, the stitching was supposed to be speedy; otherwise, people would suffer in the cold. Each community develops its own culture.”